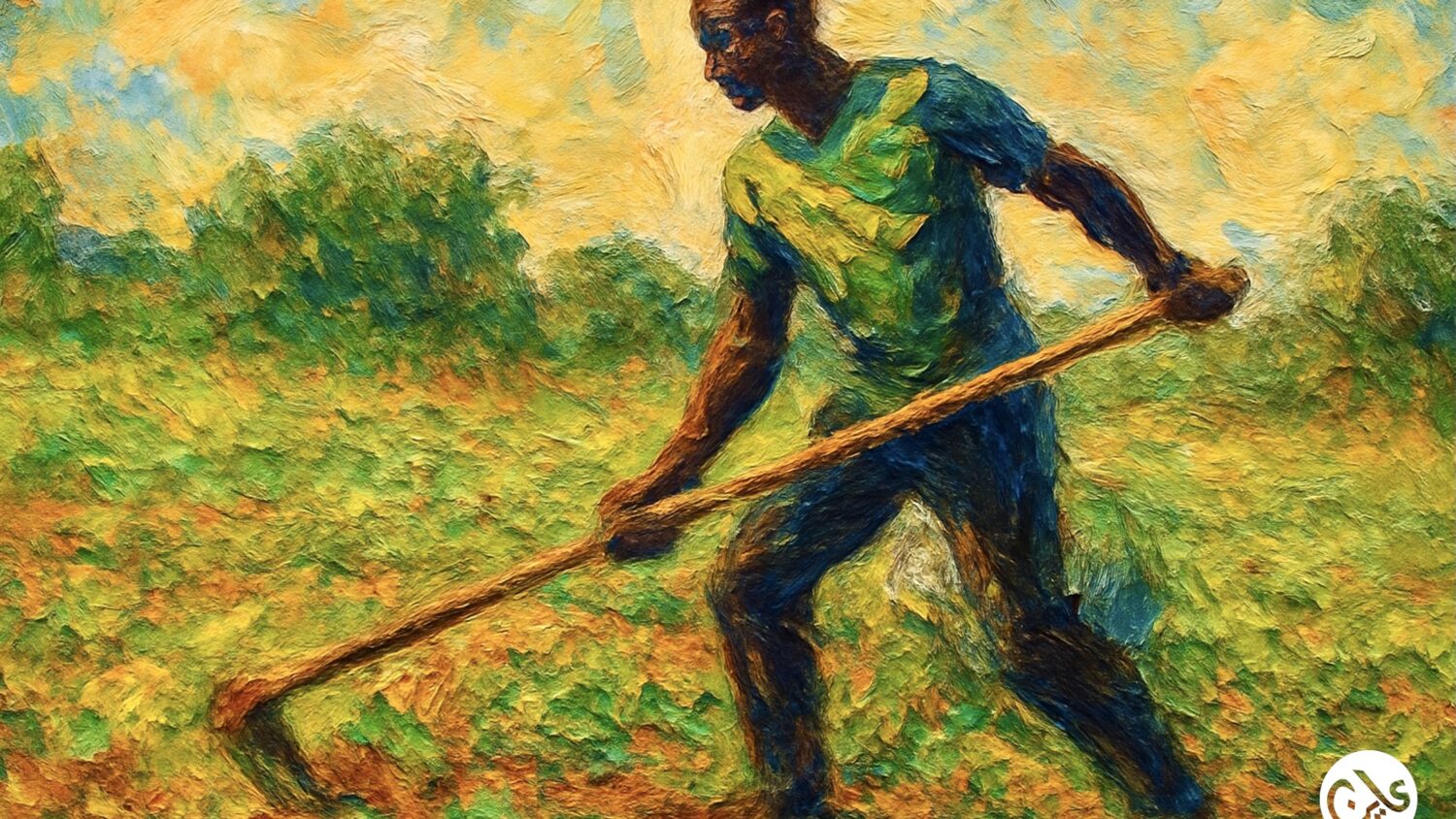

South Kordofan: No farming amidst ongoing famine

13 January 2025

Farmers across the vast state of South Kordofan, once considered a breadbasket for the country, are unable to cultivate. Residents told Ayin they are forced to farm in an extremely limited capacity: along mountaintops and areas surrounding homes, after the war has curbed any opportunity for regular agricultural activities.

For the third year in a row, the agricultural season in South Kordofan has failed as a result of the deteriorating security situation and farmers’ difficulty reaching agricultural areas. The ongoing military battles have also forced thousands of farmers to flee from production areas to the cities.

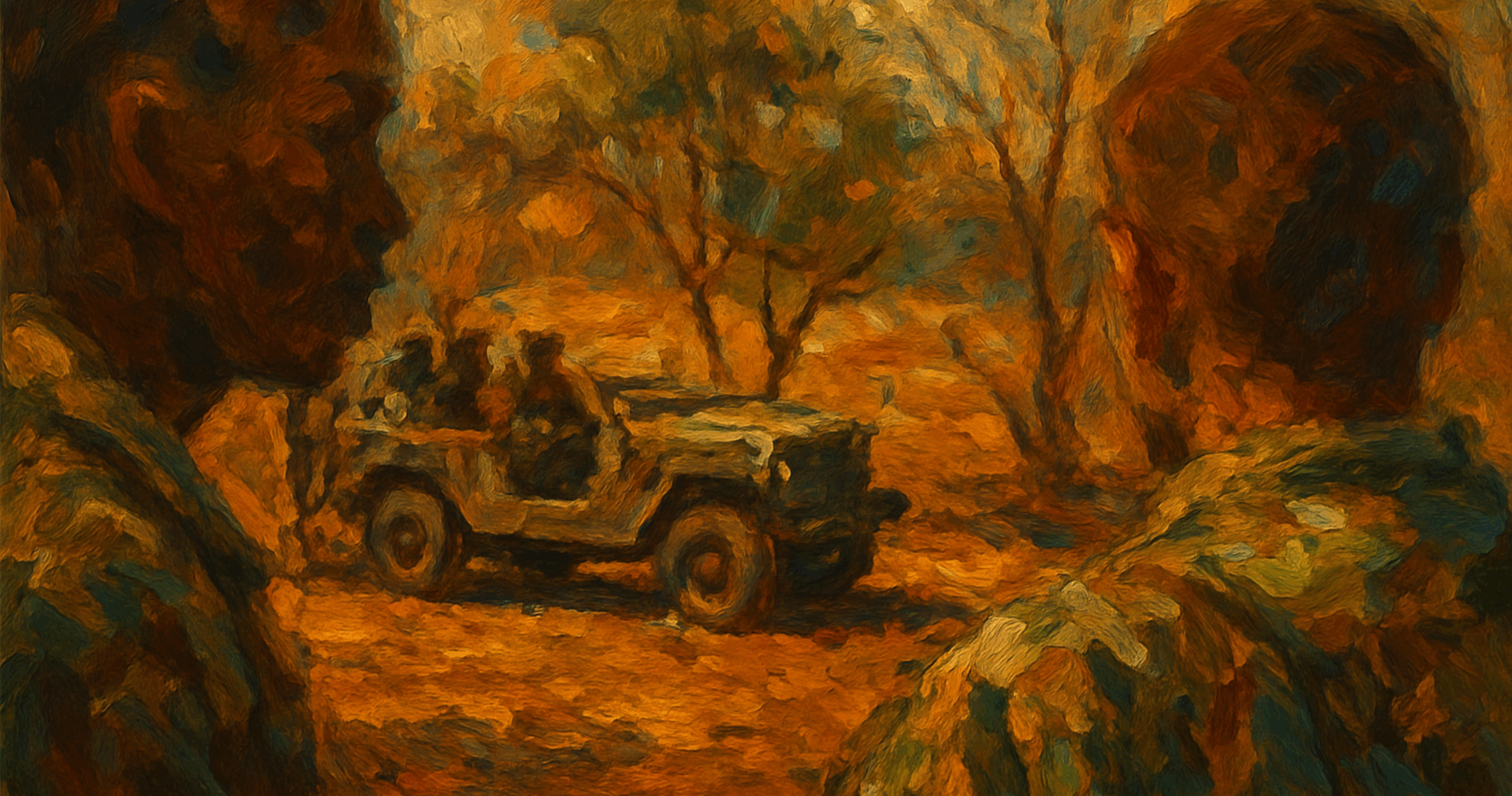

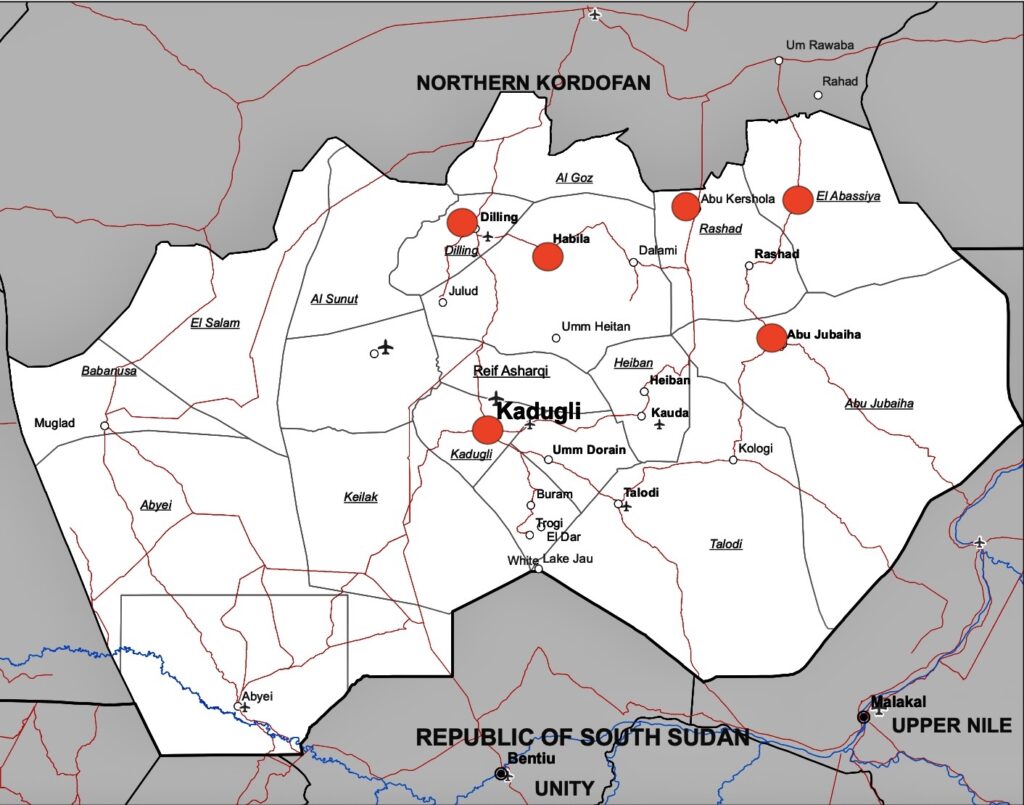

Military conflicts are getting worse in South Kordofan State between the SPLM-North and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) on one side and the army on the other. The insecurity has led to deteriorating humanitarian conditions and the displacement of people fleeing from the trapped cities of Dilling and Kadugli.

The once fertile agricultural projects in the town of Habila in the Nuba Mountains were abandoned early on in the current war after a mass exodus of the town’s residents. The country’s food production ranks South Kordofan State second only to Gedaref State. In previous years, Habila contributed to roughly 35% of the country’s maize production.

No security, no farming

Similar to Habila, other areas within the state, including Kadugli, Dilling, and the eastern localities of Abu Jubaiha, Al-Abbasiya, and Abu Karshola, failed to farm this year. Local farmers told Ayin that they had also failed to obtain basic farming supplies, such as fertilisers, pesticides, seeds, and fuel.

Omar Kajo, a resident of Kadugli, told Ayin that the people in his region were forced to return to farming in the high mountains after abandoning it for years. This limited farming may achieve self-sufficiency, instead of cultivating large areas as needed to achieve a surplus and feed other parts of the state and country.

“The start of last year’s planting season coincided with widespread security disturbances in South Kordofan State,” Kajo said. “This led to a significant decrease in the amount of land under cultivation; the actual planted area pales in comparison to the population’s requirements.”” Kajo anticipates “disastrous repercussions” during the upcoming summer, when signs of famine have already surfaced.

The situation is similar in the Abu Jubaiha area, located in the eastern part of South Kordofan State. It has faced continuous crop failures since the outbreak of the current war, resulting in dire humanitarian conditions for its inhabitants. Known for its mangos, corn varieties, and sesame, several neighbouring towns have traditionally relied on Abu Jubeiha’s once bountiful harvest.

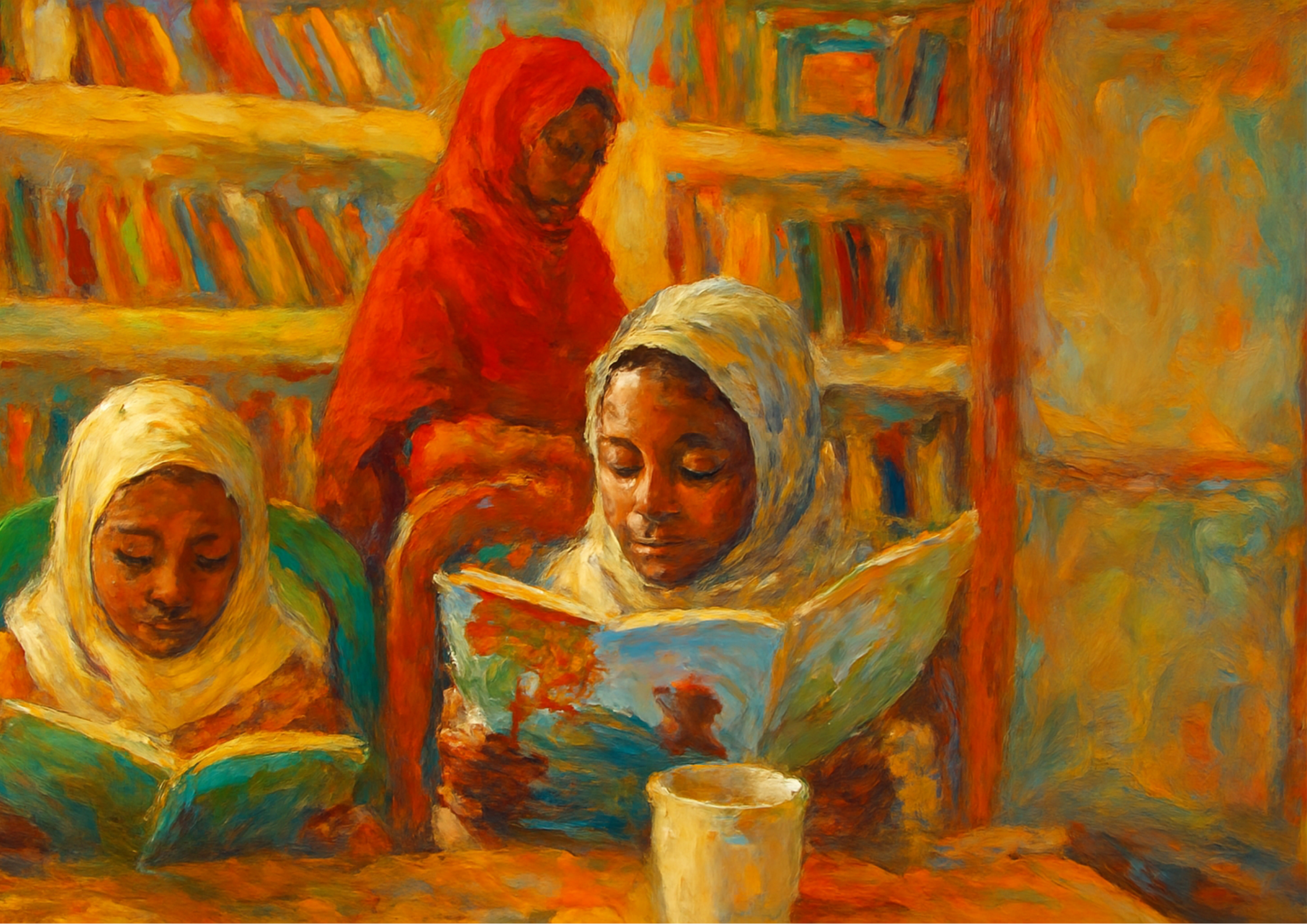

According to Abu Jubeiha resident Jadallah Othman, three major farming projects have ceased altogether. “Most of the displaced residents from those areas have relocated to the town of Abu Jubeiha and are currently residing in shelters,” Othman stated. “So the local need for harvests is greater than ever but no one is able to do so.”

Al-Abbasiya, Kartala, Karshola

Insecurity has also plagued the Al-Abbasiya area in northeastern South Kordofan State. Unable to cultivate in large areas, says resident Fathi Jabrallah, many resorted to farming in small patches around their homes, a practice locally called “Al-Jabraka”.

“With the start of the agricultural season last June, armed men from the Rapid Support Forces attacked farmers near Al-Abbasiya during land preparation operations,” Jabrallah said. “They took a tractor, fired shots in the air and warned farmers against farming in the area before releasing the tractor after residents paid 300,000 pounds (roughly US$88).” The town has become a host for the displaced, including those from Khartoum, Jabrallah added.

In Kartala, a town in the Nuba Mountains, farmer Munim Karuru says that ongoing insecurity, delayed rains, and economic challenges have affected roughly 30–40% of the agricultural area. “This season, farmers faced multiple obstacles, not only security-related but also economic, the most prominent of which was the difficulty in providing fuel, as the price of a jerrycan of gasoline reached 140,000 pounds (roughly US$ 42), which made it out of reach for the majority of farmers,” Karuru said. Without access to fuel, Karuru said, local farmers were only able to farm small patches, enough to feed their immediate families during the summer season and nothing else.

He stressed that even the largest producers today only cultivate between 500 and 1,000 acres, divided between corn and sesame, noting that farming only takes place near homes for security purposes—no more than 10–15 kilometres from the house. Previous attempts to protect crops from the armed groups had ended badly, Karuru added. Last year, a merchant hired young men from the area to guard his agricultural land, but the Rapid Support Forces killed three of them while they were protecting his crops. “This was a painful experience for us; it prompted residents to reduce farming instead of trying to plant as normal.”

The situation in Abu Karshola in northern South Kordofan State is no different from elsewhere, as farmers have been subjected to armed attacks and the looting of their machinery. In June 2025, armed men on motorcycles shot at farmers and looted a tractor, says tractor driver Muhammad al-Nour. A similar attack took place a month later, Al-Nour said, making regular farming a near impossible task.

Kadugli, Dilling and the Nuba Mountains

The lack of harvests across the state detrimentally affects both present and future food security levels at a time when several areas are contending with severe food insecurity. According to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) and UN agencies, South Kordofan’s capital, Kadugli, is now facing famine. Under a siege between the army, the RSF, and the SPLM-N, the capital remains cut off from trade and aid. Facing a similar military siege, the UN suspects the town of Dilling faces similar conditions but lacks data due to the ongoing siege.

“We are suffocating under a siege from all directions,” says Kadugli resident Hassan Ahmed. All roads linking Kadugli to productive rural areas have been closed, he added, describing the siege as a “systematic economic war”. Since July last year, some residents have resorted to eating wild grasses for survival, walking long distances to search for edible plants.

Another local source in Kadugli, who spoke to Ayin on the condition of anonymity, reported that the situation in the state capital worsened after civilians raided the main market in July last year. In an act of desperation, civilians ransacked grain stores and shops after facing a 300% surge in food prices and accusations that the army was hoarding humanitarian aid while the city faced starvation. The source added that exorbitant commissions on banking transactions, reaching as high as 50 percent, drove up prices and reduced the purchasing power of citizens further. The opening of limited access points through areas controlled by the SPLM-N provided temporary relief but was not sufficient, the source added.

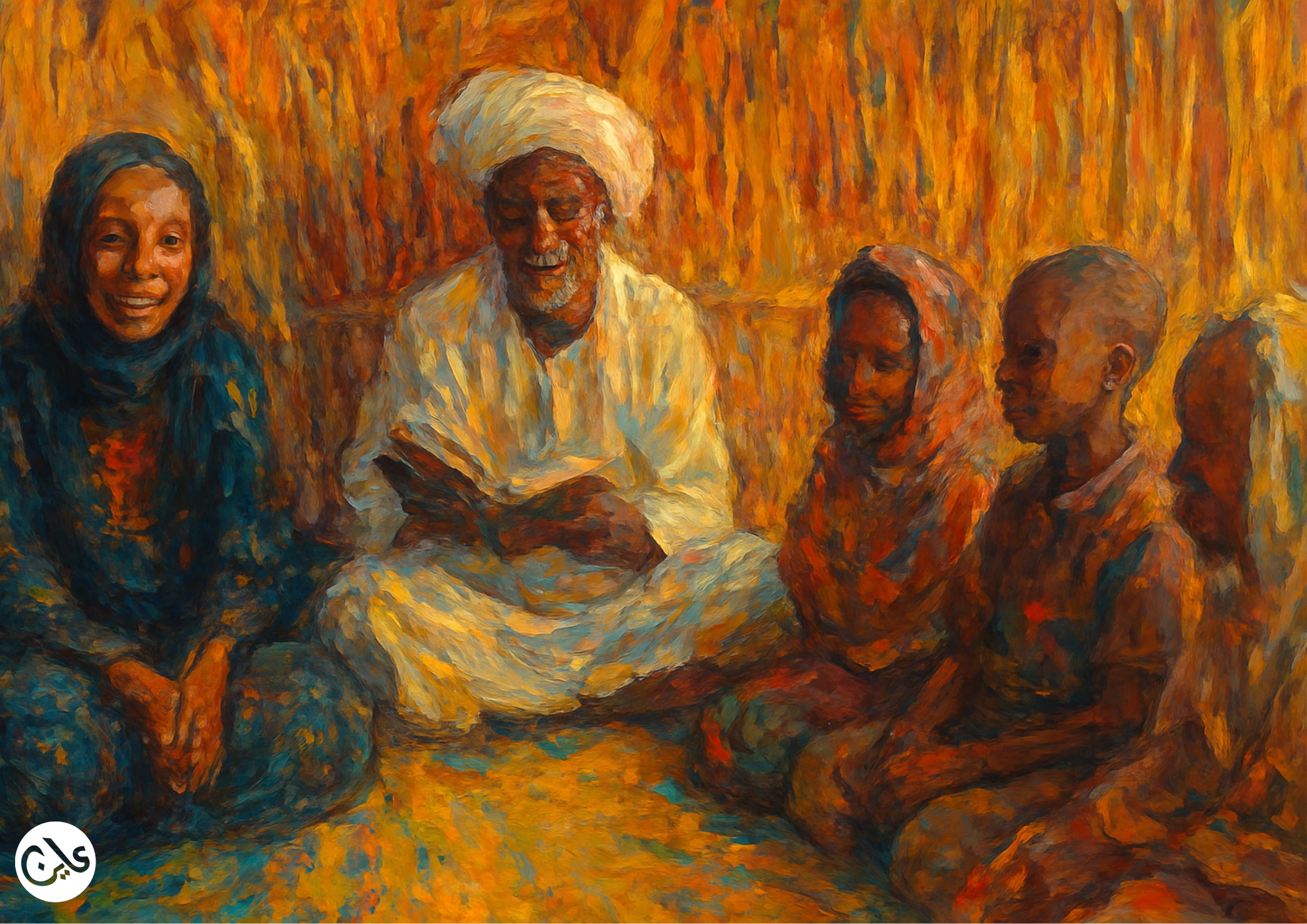

The famine in Kadugli has induced the displacement of large numbers of people to villages and small areas under the control of the SPLM-N to search for food. “This displacement is not due to direct military clashes, but rather to the famine itself,” Ahmed said. The influx of displaced people to villages under SPLM-N control has exacerbated an already desperate situation, Ahmed says, as the host communities are compelled to share ever-scarce food supplies. Many of those fleeing Dilling and Kadugli were unable to harvest the meagre crops they had planted, local sources told Ayin, while others were forced to sell their harvests to raise funds to escape the area.

Displaced by hunger

Ahmed believes conditions in Kadugli and the rest of the state will only worsen due to the lack of farming and tools to counter pests. “Current agricultural practices are limited locally and cannot bridge the food gap without achieving peace, opening roads, and securing humanitarian corridors,” he added.

To Ahmed, the famine in South Kordofan is more dangerous than the war itself. It kills silently and forces even higher levels of displacement than insecurity. Ahmed estimates roughly 90% of Kadugli’s residents left the city for other areas of Sudan or neighbouring South Sudan, not because of the violence but due to hunger.