The Arab Gulf is ruling Sudan by proxy

The Gulf’s long-term political and economic interests in Sudan may prove the key de-stabilizer to the protest’s nearly five-month long struggle for political reform in the country.

“We do not want Saudi aid even if we have to eat beans and falafel!” – a new chant has joined the protesters at the sit-in in front of the army headquarters. Sudanese citizenry are rejecting an offer of US$3 billion from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), claiming the funds are designed to support the Transitional Military Council (TMC) to wrestle power from the protestors.

“We don’t want their money,” says Mohamed Alghaily, a trader and protestor at the sit-in site, holding a placard with one hand while smoking a cigarette in the other. “They have always supported Bashir and now they want to do the same with generals (TMC).”

The Arab Gulf and the TMC

Three weeks after a protest sit-in at the army headquarters that toppled former president Omar al-Bashir, Sudanese civil society under the Freedom and Change umbrella movement continues to demonstrate, distrusting the Military Council and their foreign backers. One of the biggest protests demonstrations took place last week calling for civilian rule.

But recent foreign aid from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates may provide the Transitional Military Council (TMC) more leeway in negotiations and cling on to power, says Mohamed Yusuf Mustafa, the head of the Sudanese Professional Association (SPA) –the umbrella group that spearheaded the protests.

According to official statements from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the UAE, a total of US$3 billion will be donated to Sudan with US$500 million collectively deposited in the National Bank of Sudan. So far, only the UAE has deposited US$250 million on 2 May.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE have not met the SPA leaders or informed them of the fiscal support, Mohamed Yusuf told Ayin. So far, Yusuf said, they have met high-level officials from Western countries while only Egypt has offered a consular officer from the Arab countries.

“The support for the military council will be bad in the long term and short term,” Yusuf said, “In fact, any support of the council will not be accepted, we will fight against this until Sudan is truly independent.”

Yusuf’s wariness towards support from the Gulf countries is not unfounded.

The war in Yemen

Saudi Arabia had maintained a close working relationship with former president Bashir and the ruling National Congress Party. Bashir’s former influential office manager and minister Taha Osman Hussein, for instance, now works as the Horn of Africa advisor for the Saudi Kingdom and recently returned to Sudan.

Under Bashir, Sudan has provided the largest contingent of soldiers for the Saudi Kingdom’s proxy war in Yemen, supplying the Saudi-led coalition with thousands of foot soldiers, totalling as many as 14,000 militiamen over a four-year period. The TMC leader General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan headed the recruitment of Sudanese troops who fought in Yemen. Many of these recruits came from Burhan’s TMC deputy, General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo –better known for his nickname “Hemeti”, who leads the infamous Rapid Support Forces –a paramilitary force previously set up by Bashir to counter Darfur rebellions. Hemeti said Sudan would continue participating with the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen, according to the state news agency, SUNA.

“Without us, the [rebels] would take all of Saudi Arabia, including Mecca,” said former Sudanese fighter Mohamed Suleiman al-Fadil in an interview with the New York Times upon his return to Sudan after serving in Yemen.

According to Suleiman Baldo, a Senior Policy Advisor to the Enough Project, an advocacy think tank, the Gulf countries’ support is meant to ensure the TMC remains in power to continue fighting in Yemen. “They don’t want a civilian government,” Baldo told Ayin, “they want a military that can decide on its own to engage in foreign wars.”

Sudanese militias are not the only commodities the Gulf countries import.

Land grabs

Prior to the ousting of Bashir, several Gulf countries made vast agricultural investments in Sudan, grabbing large swathes of land to export food to cash-rich, food-poor Arab investors. The former ruling party, desperate for cash and facing skyrocketing inflation and a lack of foreign currency circulating in the market, gave out land to several Gulf-based investors. In 2016 the Saudi government leased 1 million arable acres in the east of the country.

Sudan is one of the “leading” countries in which authorities confiscate land from citizens, according to the World Bank. Between 2004 and 2013, roughly four million hectares of land was redistributed to local and foreign investors. Under Bashir, authorities used the widespread lack of official ownership documents to capture private land and redistribute it to foreign investors, government, military officials and businessmen close to the government, according to a report by the Sudan Democracy First Group. With Bashir and his National Congress Party out of the picture, key Gulf agricultural investments may be jeopardized.

Material considerations are only a part of the Gulf’s interest in Sudan maintaining the former autocratic status quo. Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE used financial and military support to quell the Arab Spring in late 2010 – 2011 and bolster autocratic allies. Both countries have a shared vision to counter the influence of Iran, Qatar and Turkey and political Islamists movements as an act of self-preservation. And both royal kingdoms have no tolerance for any democratic contagion that could stir political aspirations among their own populace.

Regional Blocks

The two gulf countries’ interest in Sudan is nothing new. According to the Central Bank of Sudan, the UAE and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia have invested at least US$3.6 billion in Sudan since 2016 –-largely to abandon its traditional ally, Iran. But “Sudan has tried to eat at all the tables under al-Bashir’s rule” says Baldo, “keeping the back door open with Qatari and Turks while aligning with Saudi Arabia and the UAE –in the end losing both regional blocs.”

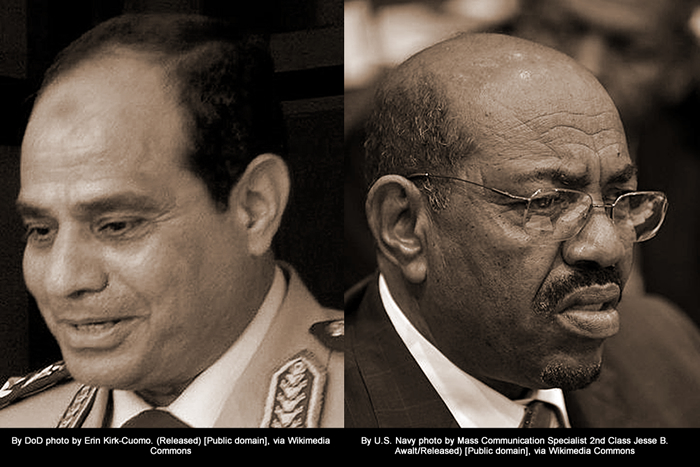

Sudanese protestors suspect Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah Sisi harbours similar views to that of his Gulf neighbours. Sisi’s recent intervention calling for Sudan’s military to stay in power for three months was widely rejected by protestors in Khartoum. “Tell Sisi,” demonstrators shouted outside the Egyptian Embassy in Khartoum last month, “This is Sudan, the border stops at Aswan!”

Sudanese remember well how Egypt’s Arab Spring in 2011 soon stumbled after President Sisi and Gulf allies quashed a short-lived democratic system and instilled another authoritarian regime where he may reside until 2030.

While the Sudanese demonstrators remain adamant and continue to protest, cognisant of the failures of the Arab Spring movements in the past, time may play in the Military Council’s favour. Already signs of internal squabbling within the Freedom and Change movement weakens their political positioning vis-à-vis the Military Council, who remain steadfast in their attempts to cling to power, Baldo says. “As long as [the TMC] continue to satisfy Saudi Arabia and the UAE and maintain the economic interests of their militias and armies intact –away from civilian interference-they may remain intact.”