Death and detention: the struggles of Sudanese migrants crossing into Egypt

16 July 2024

In the past month there has been a significant increase in fatalities among Sudanese asylum seekers that are smuggled across the border into Egypt amidst the sweltering heat. On 11 June, the Sudanese consul announced the burial of 51 Sudanese bodies –all refugees who attempted to cross the border into Egypt over a three day period. The consul said they expect this number will rise as they continue to discover more cases.

For 15 months, the army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have fought a war of political and economic dominance, displacing roughly 10 million civilians in the process. From this number, 640,000 Sudanese have fled across the border into Egypt. This statistic, however, only accounts for those who have crossed the border legally and registered as asylum seekers. Meanwhile, hundreds of Sudanese are smuggled across the border into Egypt daily.

“In a tragic incident on 12 June during the night shift at Aswan University Hospital, the surgery department received many deaths and injuries from the Sudanese-Egyptian border,” a medical source from the hospital told Ayin. “The influx of cases continued for a full 24 hours.” The medical officer said 90% of the cases of death were due to severe dehydration and heat stroke. “The next day, additional cases arrived at the hospital due to an accident in the desert, resulting in one death which increased the total to 51, and more than 20 injuries,” the same source added.

Travel trepidations

The smuggling route linking Egypt and Sudan presents a myriad of challenges –everything from a harsh scorching desert by day to freezing nights. Moreover, the smugglers who carry them often subject the Sudanese asylum seekers to abuse, coercion, sometimes even abandonment within the desert, several asylum seekers told Ayin. Ismail*, a young Egyptian residing in the southern city of Aswan, voluntarily washes and buries the deceased Sudanese in the southern border town. Ismail stated that the journey spans approximately 450 kilometers through the desert whereby Sudanese and Egyptian smugglers exchange the smuggled passengers at a location referred to as “the storage”.

The “storage locations” often exploit the Sudanese asylum seekers, Ismail added. “If something costs 5 Egyptian Pounds normally, the same commodity will cost 200 at one of these rest areas, a bottle of water is high, reaching up to 100 pounds (US$2).” Acquiring a bottle of water can be a matter of life and death in Aswan’s summer heat. On 6 June, Aswan recorded one of the highest temperatures ever recorded in the region, nearly reaching fifty degrees Celsius (122 degrees Fahrenheit). Most of the Sudanese refugees arrive in Aswan in a critical condition, Ismail added, due to dehydration. Some do not make it and are buried in the nearby mountains. “The graveyards dot the desert route between Sudan and Egypt.”

If not the heat, then the reckless driving of the smugglers themselves can place the lives of Sudanese in danger. Fearing arrest along the 12-hour journey, Ismail said, the smugglers often drive at 140 km per hour (87 mph) and will increase to 200 km per hour (124 mph) if pursued by border security forces.

Death journey

Essam*, a 46-year-old Sudanese father of six children and his wife found themselves with no option but to search for safe passage to Egypt via smugglers after Egyptian authorities delayed in issuing them visas. Essam and his family used to live in Sudan’s capital sister city, Omdurman, when clashes between the army and RSF compelled them to re-locate to his aunt’s house in west Khartoum, Al-Hila Al-Jadeeda. But shelling and crossfire by the warring parties followed them there, forcing them all to move again, this time north to Wadi Halfa, Northern State. The family remained in Wadi Halfa for three months, residing in dire conditions, Essam said.

After 10 June last year, Egypt officials changed their once progressive visa policies towards Sudan, forcing Sudanese to seek visas and security clearance to acquire entry. According to Sudanese citizens at the border, obtaining a visa can take 4 – 7 months, prompting many to use smuggling routes as a desperate alternative.

“I had heard people talking about smuggling [across the border], I was apprehensive, but then I could never imagine the hell that awaited us in Sudan due to the war and the dire situation in Halfa,” Essam said. “We decided to take the risk and undertook the smuggling journey to Egypt.” After speaking to brokers who claimed they would leave at 4 am the following day and reach Aswan in a matter of hours – the actual journey took four days.

The smugglers generally used 4X4 Toyota Hilux pickups, invariably over-filling the vehicles for the maximum profit, according to several Sudanese sources who have taken the arduous journey. Those who paid more could sit in the cabin, while others would be forced to sit on top of the luggage and tied with ropes to prevent them from falling as the vehicle speed off across desert terrain.

Essam had to sit on top of a large water bottle and nearly fell off several times as they drove at breakneck speeds of 200 kilometers per hour (124 mph). He had to press his full weight on his children to ensure they did not fall out of the vehicle. At 1am the following day, anti-smugglers pursued their vehicle inducing them to drive at even higher speeds, eventually a tire burst forcing their vehicle to career into a sand dune and allowing for the anti-smuggling unit to catch them. Fortunately, one of the smugglers’ rifles jammed, ensuring Essam and his family did not find themselves in crossfire.

Eventually the anti-smuggling patrol released the Sudanese migrants and arranged for Essam and his family to finally reach Aswan.

Essam and his family are now legally registered with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), but they continue to face harassment from the Egyptian security forces and social harassment from citizens. These citizens are influenced by the governmental and local campaigns that blame the economic struggles on refugees with officials citing the economic “burden” of hosting “millions” of refugees.

“There have long been targeted media campaigns against Sudan in Egypt on political and cultural levels, as well as issues related to race and colour,” says Abeer Mustafa, a human rights defender who supports immigrants. Abeer says the security personnel in Egypt lack knowledge of the international laws which refugee’s rights in Egypt while the UN refugee agency often neglects Sudanese refugees. “In Egypt, security concerns often outweigh humanitarian considerations.”

Sudanese refugees often face systematic harassment in Egypt by the public and officials, even those with UN refugee cards, says Sara Creta, an investigative journalist who has reported on Sudanese immigration to Egypt. “This is due to a systematic campaign by the Egyptian security apparatus to prevent Sudanese refugees from claiming asylum, often under the guise of national security and anti-smuggling operations,” Creta told Ayin.

While a harrowing, near-death experience, Essam and his family are considered “lucky” for not being detained and deported in comparison to hundreds of other Sudanese who are caught attempting an illegal crossing.

Interceptions

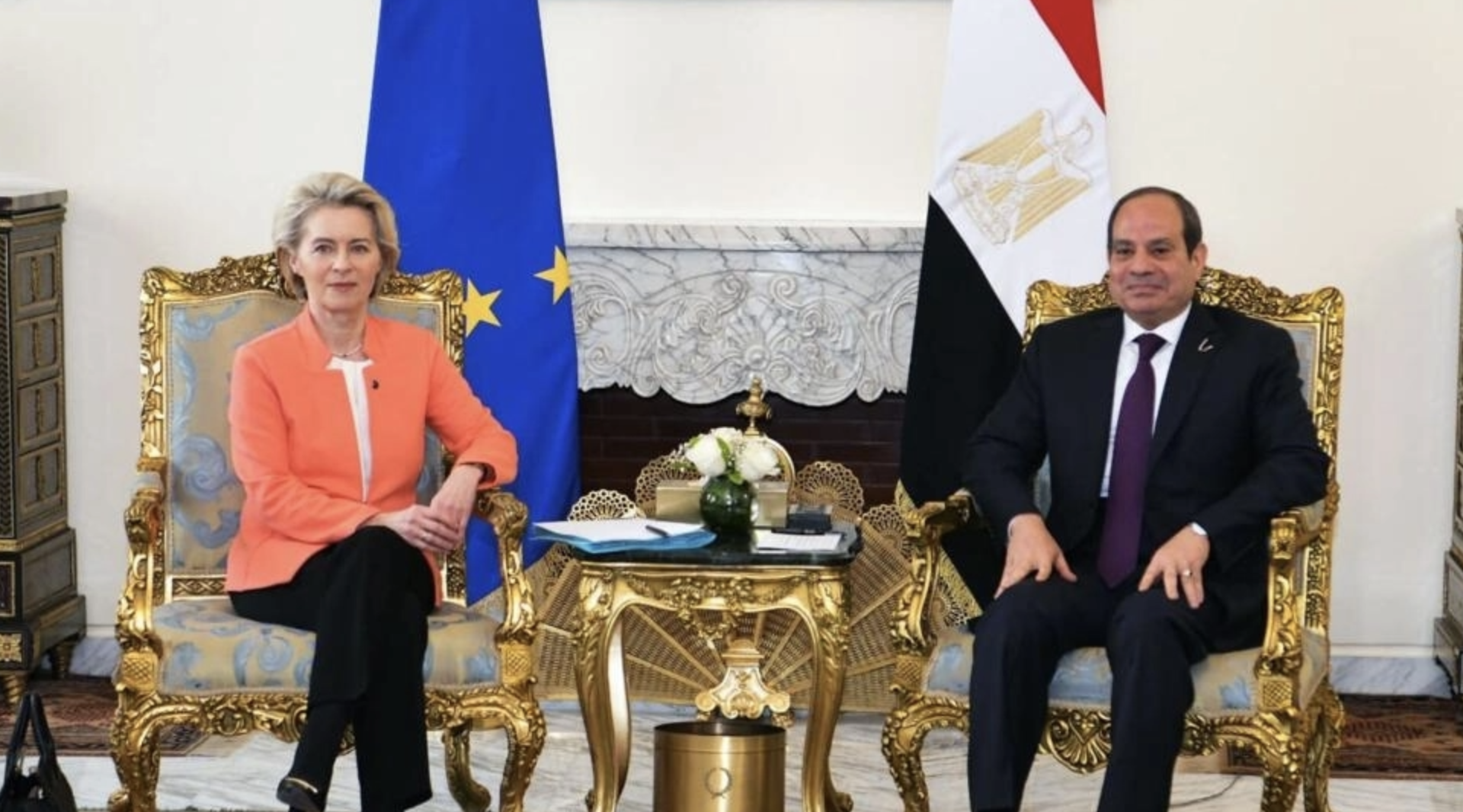

Egyptian security forces are determined to prevent Sudanese asylum seekers from reaching Egypt, according to an Egyptian security officer who spoke to Ayin on the condition of anonymity. This appears to be in conjunction with the European Union who has provided Egypt with a €7.4 billion deal in March that allocates €200 million for migration management. In October last year, the EU and Egypt signed an €80 million cooperation agreement, which included building up the capacity of Egyptian Border Guard Forces to curb irregular migration and smuggling across the border.

The Egyptian security officer told Ayin that there are three key interception points they use to arrest smugglers and their Sudanese passengers. One point, located on the western side of the Nile and parallel to Halfa and Shakit, is patrolled by the K16 intelligence battalion and Argin border guards. Another interception point takes place along a famous smuggling route on the eastern side of the Nile where three different battalions operate. The source confirmed there is a detention center based in this area. Another interception point, the source revealed, is in the disputed Shalateen area, where both Sudan and Egypt claim ownership.

Egypt’s European-backed anti-smuggling operations appear to have successfully curbed the entry of Sudanese, desperate to secure their lives from war-torn Sudan. In Aswan alone, a city of roughly 1.5 million, Ayin identified seven detention centers set up to hold Sudanese asylum seekers and return them back to Sudan. The identified detention centers include:

- Edfu police station: located in Edfu center nearby Edfu government office and Edfu city council- Aswan Governorate.

- Kom Ombo police station: located in Kom Ombo center nearby Kom Ombo city courthouse- Aswan Governorate.

- Nasr El-Nouba police station: located in Nasr center nearby Family court-Nasr El-Nouba-Aswan Governorate.

- New Daru police station: located in Daru center, nearby The Egyptian post-Daru branch- Aswan Governorate.

- Aswan first police station: located in Aswan center, nearby Kournaish Al-Nile Street.

- Aswan Second police station: located in Aswan center, nearby street 12- Aswan Governorate.

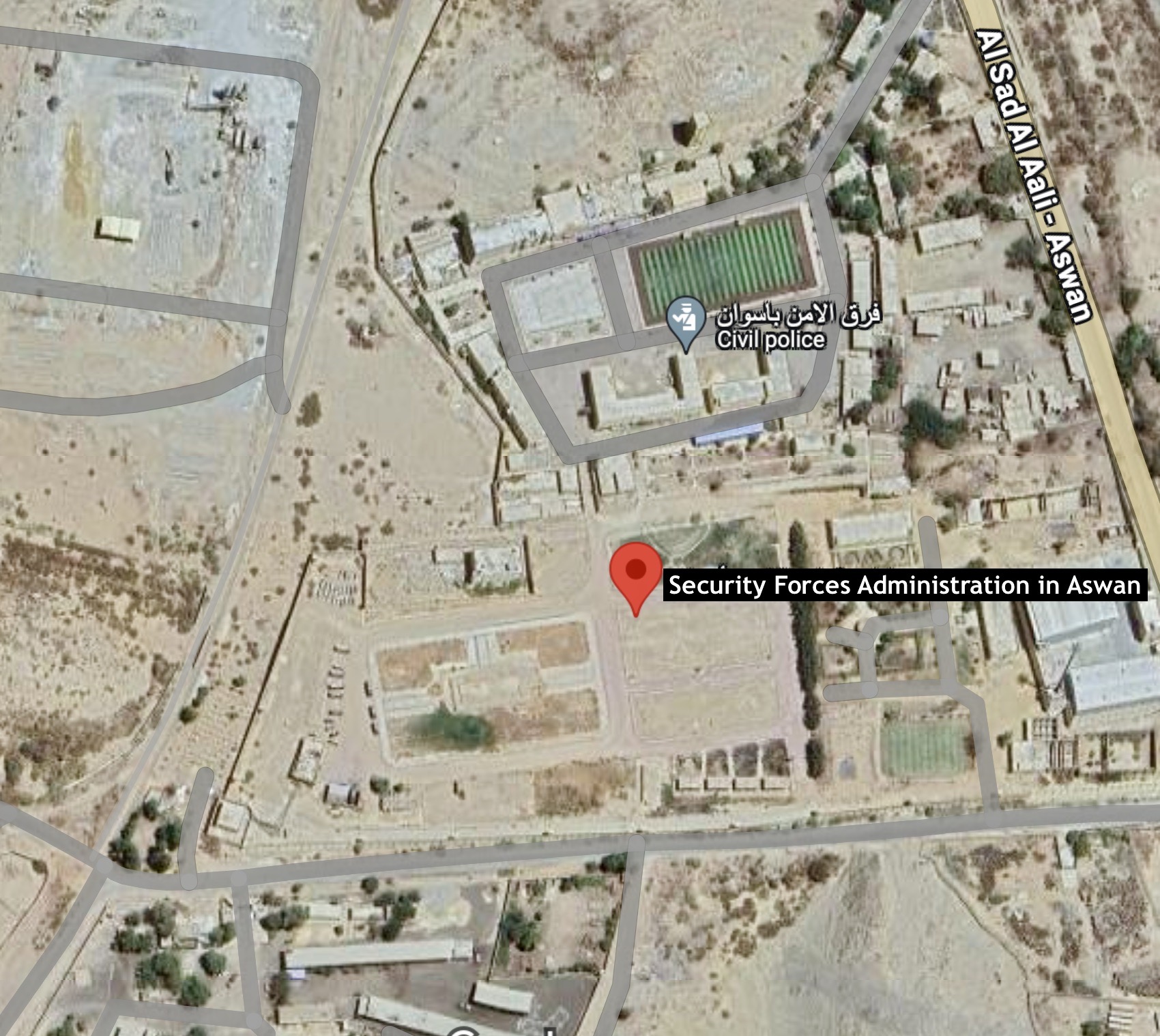

- Aswan Security forces Administration: located in Aswan center Shalal area, nearby Al Sad Al Aali Street- Aswan Governorate.

Corroborated by several Egyptian sources, including Sadia*, an Egyptian volunteer who is engaged in a grassroots initiative to assist Sudanese asylum seekers in Sudan. “Every two days we try to send different people to the detention centers to deliver some aid such as food and clothes as most of them lost their belongings during the journey,” Sadia said. “What breaks our hearts is the presence of children in some of the detention centers, so we try to deliver diapers and milk to them.” The volunteer identified 20 children in one of the detention centers and believes there are many more in other centers.

The detained Sudanese asylum seekers are normally held for 15 days to a month before deporting them back to Sudan and stamping their passports with a five-year entry ban. Some, however, never return at all. According to Sadia, several Sudanese refugees have died at the Aswan Security Forces Administrative center in the Al-Shalalt area, due to assaults by other Egyptian inmates who are serving long-term jail sentences. There are roughly 150 – 200 Sudanese currently being detained in this facility, Sadia told Ayin, with many held for longer periods exceeding seven months.

Treated and deported

Police officers are in every hospital in Aswan, Sadia added, often looking for Sudanese who have entered the country illegally. “Once their medical treatment is over, the police detains them.” A medical source at Aswan University Hospital told Ayin that they help patients to leave the hospital if their injuries were minor, to protect them from the security forces. “We used to smuggle patients out of the hospitals if their treatment didn’t require hospitalisation and we would write a fake name on the list.”

Zeinab*, a Sudanese asylum seeker, told Ayin that she fell from the four-wheel drive vehicle during the smuggling attempt, injuring her leg. She emphasized that she was advised by the smugglers to endure the pain and avoid going to the hospitals in Aswan, as she learned she would be arrested and deported if she sought medical help there. “In our previous investigation we found that injured refugees often face immediate deportation without proper medical care or assessment of their asylum claims, driven by strict and expedited deportation protocols by Egyptian authorities,” Sara Creta said.

In June, the Egyptian authorities announced deporting 700 Sudanese asylum seekers who had entered the country through smuggling, transporting them via 10 buses that included numerous families including children and elderly individuals. While still high, in other months authorities have detained and deported even more people. The UN refugee agency (UNHCR) estimated that 3,000 people were deported to Sudan from Egypt in September last year.

“The deportation of 721 Sudanese nationals involved detentions in secret military bases and rapid deportations without due legal process,” Sara Creta said. Conditions in these detention facilities are cruel and inhumane, with overcrowding, lack of access to toilets and sanitation facilities, substandard and insufficient food, and denial of adequate healthcare, Amnesty International reported. “These actions are part of a broader effort by Egyptian authorities to manage and control refugee influxes, often bypassing legal norms and refugee conventions,” Creta added.

Abeer Mustafa says Egyptian authorities are contravening international human rights law by deporting asylum seekers from a conflict zone. “All the countries that adhere to international law do no deport asylum seekers from a war zone back to those warzones, where their lives may be at risk. The right to life is fundamental in all the international laws,” she added.

Immigration lawyer, Dr. Isam Hamid, disagrees. “The Egyptian state –just as any- has the right of sovereignty over its land,” he argues. “The state has the right to deport those who came illegally or are staying without a permit.”

Repeated communication attempts to contact Egyptian officials from the ministry of foreign affairs and interior were left unanswered.

The UNHCR says that since refugees are not protected by their own governments, the international community steps in to ensure they are safe and protected. Countries that have signed the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol are obliged to protect refugees on their territory and treat them according to internationally recognized standards. Egypt signed the convention in 1981.

A benefit to Egypt

Despite the Egyptian authorities’ harsh, often illegal treatment towards Sudanese asylum seekers, they are receiving considerable international support in the process. In May 2023 near the beginning of the conflict, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) provided $6 million in to help Egypt contend with the unfolding humanitarian crisis taking place in Sudan. This year in March, the US State Department announced that America had provided $986 million in humanitarian assistance for the people of Sudan and neighbouring countries. The European Union (EU) on the anniversary of the war on 15 April, committed to spending €896 million on humanitarian aid to Sudan and neighbouring countries such as Egypt. While Egypt benefits from international finance, authorities are also cashing in on Sudanese migrants. A decree introduced last year calls on any Sudanese migrant who are found to be undocumented in Egypt or whose residencies have expired must apply to “legalize their status”. Authorities are demanding $1,000 for each individual in this process, failure to pay will result in their deportation back to war-torn Sudan. “We have to question where the funds provided by western countries such as the US, Canada, and the EU to Egypt for addressing the crisis of the Sudanese refugees have gone,” Abeer Mustafa asks.