Sudan’s prospects for peace, optimism despite huge challenges

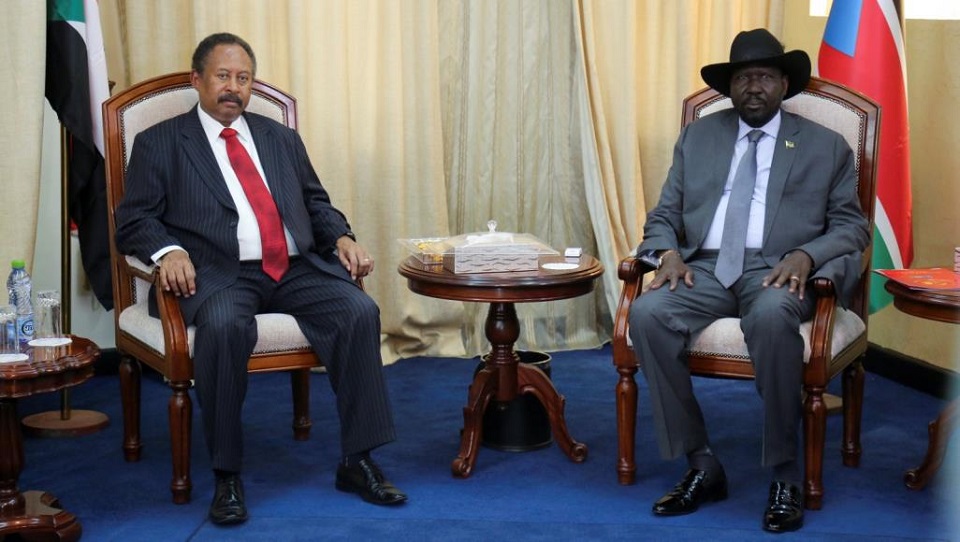

“Peace seems to be in the air in Juba these days,” comments Angelo Wello, a pastor and charity worker based in Juba, South Sudan. Wello was referring to the recent political exchanges between Sudan’s Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and his South Sudanese counterpart, Salva Kiir, along with the peace talks between Sudanese rebel groups being hosted by Africa’s newest country. Wello, like many South Sudanese, used to live in Sudan’s capital Khartoum before relocating to Juba once South Sudan gained independence in 2011 and know full well the importance of peace for both countries.

Last week in Juba, Sudanese rebel groups and the government signed a Declaration of Principles for a comprehensive peace process that paves the way for the negotiating process between the parties concerned.

While Wello’s optimism is justified, there are several dark clouds that must be cleared before truly reaching peace. The signing last week in Juba of the Declaration of Principles is a major step forward but issues such as political positions, the abolishment of militias and the lack of participation of a Darfur rebel group may ensure the skies remain downcast.

Declaration of Principles

On September 11, members of the umbrella rebel group, the Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF), Sudanese government members from the Sovereign Council –including the commander of the Rapid Support Force (RSF) militia, Lt Gen Mohamed Hamdan (aka “Himmedti”), and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) rebel group led by Chairman Abdelaziz Al-Hilu, signed the document.

The Declaration establishes a comprehensive ceasefire between the Sudanese government and armed movements, supports measures to open humanitarian access to war-affected areas, provides for the release of prisoners of war and abolishes government death sentences to leaders of armed movements. An ambitious plan, the roadmap for peace is meant to start on 14 October and be completed in a two-month period.

The government is already taking steps to build confidence amongst the parties to establish peace. Just this week, Sudan’s Sovereign Council dropped the death penalty against eight members of the Darfur rebel group, the Sudan Liberation Movement under Abdel Wahid al-Nur (SLA-AW). Last Sunday, the government released 17 prisoners of war from the SPLM-N faction led by Malik Agar. The head of the Sudan Revolutionary Front, Dr Al Hadi Idris, told Ayin that the peace deal poses as a major breakthrough thanks to the “political will from all parties and the growing interest of the Government of South Sudan to mediate.”

Constitutional re-draft

Despite these auspicious signs, major hurdles must be overcome to reach peace. For one, the new peace plan calls for amendments to the Constitutional Declaration drafted and signed by the umbrella opposition group, the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC) and the former Military Council. This demand is designed to postpone the appointment of legislators and state governors as well as re-model other government structures until the peace process is complete. “We will re-draft this document and reconstitute all the structures presented in the Sovereign Council, the Council of Ministers, the parliament, states and top leadership posts,” senior SRF negotiator Ahmed Tugud Lissan told Ayin. The SRF believes government positions delegated in this transitional period is not inclusive of the rebel forces and mishandled by some members of the FFC to acquire power. “We all agree on re-opening this document (the constitutional declaration),” he said. “What is going on now is a systematic monopoly and deliberate exclusion of large sectors –if this is done, it will lead the country to total collapse.” According to Tugud, the demand to amend the constitution to allow more government participation is not simply designed to provide the rebel leaders government positions. The move, he says, is designed to ensure improved representation from marginalised areas in the country and to counter some individuals in the FFC who have attempted to appoint their own cadres into political posts.

The head of the SRF, Dr Al-Hadi Idris told Ayin the signed Declaration of Principles “come within the framework of measuring the seriousness of the government side. We, therefore, demanded the release of prisoners of war and the amendment to the Constitutional Declaration.” The government has already released 17 prisoners of war and announced plans to increase the ministerial and Sovereign Council seats to potentially accommodate more political participation.

But whether the transitional government under Prime Minister Hamdok, and the FFC that nominated it, are willing to wait months prior to establishing a legislative council, among other posts, is yet to be seen. Dr. Suleiman Baldo, Senior Policy Advisor to the Enough Project, fears the SRF’s insistence on delaying the formation of government institutions, the legislative assembly, in particular, could unwittingly play into the hands of the military. “The delay in the establishment of the legislative assembly will prove very difficult for the civilian cabinet to dismantle the old regime and commence political and economic reform,” Baldo told Ayin. The former military junta are keen to delay the establishment of a civilian-led parliament that would be mandated to look into human rights issues and may explain why Sovereign Council member and RSF leader Himmedti readily led the initiative that reached the Juba peace declaration with the SRF. The military also currently controls the majority of state governors and will continue to control the federal states if delays in civilian state governor appointments are delayed, Baldo said. “Is this what the SRF really wants? Allowing the members of the former regime to maintain control with limited legal accountability?”

SPLM-N: a sovereign army or separate

A long-term reconciliation demand of Sudan’s largest rebel force, the SPLA-N under al-Hilu is the disbandment of the former regime’s militias and paramilitary units and re-modelling of the country’s army. “Reaching a satisfactory peace agreement requires a significant concession from the Sudanese government,” said SPLM-N General Secretary Amar Amoun. “This concession must include the security aspects and the restructuring of the armed forces in a way that constitutes a national army of Sudan.” If this does not take place, Amoun told Ayin, the Nuba Mountains-based rebel group will call for self-determination. Given the former regime’s use of paramilitary units such as the infamous Rapid Support Force in Darfur and South Kordofan, the SRF concur with the position but question whether self-determination in the land-locked region is tenable. “We appreciate the demand, but I do not think it will meet the support of the masses,” SRF’s senior negotiator Tugud said. Further, Himmedti is the head of the RSF and Sovereign Council member as well as being one of the richest men in Sudan. With such power and influence, it is unclear whether the militia leader would be willing to relinquish his forces to merge within a more disciplined, national army.

It is even questionable whether the likes of Himmedti and other members of the former military junta now in power will accept peace, let alone military integration. “The question is finally whether the military elements of the transitional government really want peace,” writes Sudan Political Analyst Eric Reeves. “This question is particularly exigent when we look at the records of Sovereign Council Chair General Abdel Fatah al-Burhan and Sovereign Council member and RSF commander Hamdan Dagalo (“Himmedti”),” writes Reeves. “Over the past decade, Himmedti has accumulated more Sudanese blood on his hands in conflict in Darfur and South Kordofan – as well as Khartoum and elsewhere – than any other man in the country. Is he now really ready to make peace?” According to Reeves, if the army and RSF are not brought under civilian control and free from tampering by the likes of Burhan and Himmedti, peace negotiations will lead nowhere.

SLA-AW not in Juba

Another potential stumbling block for the peace negotiations stems from the main Darfur rebel group, the Sudan Liberation Army under Abdul Wahid Mohamed Noor (SLA-AW), who did not join the Juba meeting. Noor had pre-empted the Juba meeting with a statement rejecting the talks: “We highly appreciate the efforts exerted by President Salva Kiir to resolve the Sudanese crisis and reach peace and stability, but we believe that what happened in Juba is no different from the previous foundations that led to bilateral agreements that did not achieve the desired peace and stability.” SLA-AW Spokesman Mohamed Abdul Rahman told Ayin they are willing to participate in genuine dialogue but will not simply support the dictates of the FFC and former military council. “We will not be a party to accepting a fait accompli, rubberstamping the bilateral agreement between the FFC and military council,” Rahman said. “The Hamdok government should prove that it is serious and a revolutionary government and not an extension of the old regime.”

In order to gain the Darfur rebel groups’ confidence, the SLA under Abdel Wahid has a number of prerequisites that, according to Rahman, are non-negotiable. The long list includes the dissolution of the National Congress Party, execution of the International Criminal Court warrants against former president Omar Al-Bashir, the release of all prisoners of war, the abolition of laws restricting freedom and violating human rights and the dismantlement of government militias. This position has alienated the rebel movement vis-à-vis the other rebel groups and authorities Tugud said. “Comrade Abdul Wahid continues to refuse to participate in any political process,” Tugud told Ayin. “Even those who used to stand under the SLA-AW’s flag are now tired of Abdul Wahid’s intransigence. He will not change his position and will not contribute to war or peace.”

Peace, peace and peace

In order to accommodate the sometimes disparate demands of the multiple rebel groups –not least the revision of the Constitutional Declaration and government positions in this transitional period—will not be easy, particularly in the short time-frame proposed to achieve these confidence-building measures. But the determination of people –both foreign and local—to ensure peace becomes a reality may prove the driving factor for success. Kenya’s peace envoy and former Vice-President, Kalonzo Musyoka, attended the Juba talks to encourage a comprehensive peace in Sudan and South Sudan. “We appeal to the brothers in Sudan to prioritize the interests of the people and neighbouring countries because an explosion of security conditions in Sudan will negatively affect neighbouring countries and may disrupt the region,” Musyoka told Ayin.

Perhaps the strongest proponents for peace are the war-weary citizens of Sudan. “There are three things we need before we can move ahead in this country,” said Omar Hashim, a university student in Omdurman but originally from the restive, western Darfur region. “You know what those three things are? Peace, peace and peace. We need this before anything else.”