Sudan authorities support while affected communities fear Africa’s largest dam

Sudanese and Ethiopian authorities appear steadfast in their commitment to seeing the Renaissance Dam, touted to be the largest hydropower project in Africa, completed and operational. A water-worried Egypt and the Sudanese public, however, harbour more reservations.

Sudanese and Ethiopian authorities appear steadfast in their commitment to seeing the Renaissance Dam, touted to be the largest hydropower project in Africa, completed and operational. A water-worried Egypt and the Sudanese public, however, harbour more reservations.

Proponents of Ethiopia’s massive project point to the fact that the dam may harness up to 6,000 megawatts of electricity from the Blue Nile while its detractors fear severe water shortages and potential displacement.

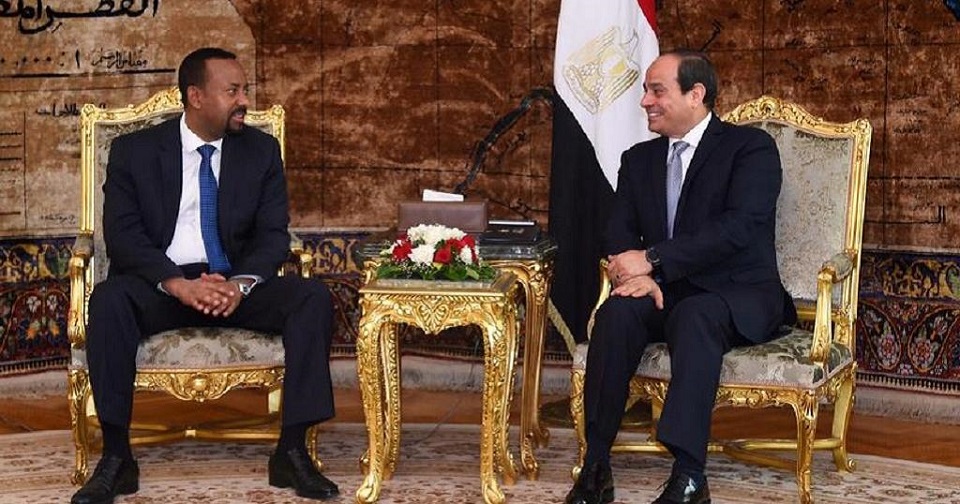

Last Friday, an Egyptian intelligence chief Lt.-Gen. Abbas Kammal and Minster of Irrigation Mohamed Abdel-Ati met their counterparts in Sudan along with Sudanese Prime Minister Abdullah Hamdok to discuss their concerns over the dam’s construction. Ethiopia and Egypt have been at odds regarding the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) since building commenced in 2011. To Ethiopia, the dam is a source of political popularity and much-needed electricity while Egypt fears its sole water source will diminish further. Sudan, however, remains internally divided between a supportive government and a wary public.

Last week, Sudan’s Minister of Water and Irrigation said U.S.-backed negotiations over the Renaissance Dam would commence in the near future. “Sudan is negotiating to preserve its water rights in the Nile river and its tributaries, but at the same time it encourage cooperation among the three parties and believes in negotiations to reach a comprehensive agreement,” he said in a statement. Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok also expressed his determination to reignite trilateral talks between Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan over the contentious dam. The premier told US Secretary of Treasury Steven Mnuchen last week he would visit Cairo and Addis Ababa to compel both parties to complete negotiations. Hamdok’s pledge comes over a month after Ethiopia’s absence from talks in Washington D.C. to agree on terms over the $4.8 billion hydroelectric project.

Ethiopia and Egypt

Ethiopia appears set to move ahead with or without further consultation with its riverine partners. A Nile-dependent Egypt has continuously lobbied for an extended time period to fill the dam via the Blue Nile, the source of 85% of the Nile’s water. Despite warnings from Egypt, the country claims it will start filling the dam in July this year. “No one will prevent us from filling the dam,” Foreign Minister Gedu Andrgachew said in news reports. “We will begin filling the dam as schedule in July.” There are practical considerations behind Ethiopia’s insistence. July is the rainy season for Ethiopia, where increased water flows via the Blue Nile are ideal for filling the dam, explains William Davison, Senior Analyst at the policy think-tank, International Crisis Group. “The Blue Nile is a highly seasonal river and the dam is already significantly delayed according to the original projections of the Ethiopian government,” Davison told Ayin. “There is a desire here to start as soon as possible, it’s a massive investment so entirely understandable.” While the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) was the brainchild of former Prime Minister Meles Zenawi, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed adopted the dam as a popular national project to potentially help unite an ethnically fractured country.

A Nile-dependent Egypt, however, relies on the river for about 90% of its water needs and about a tenth of its power, according to the International Crisis Group. It is little wonder that Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry coined the Nile issue last September as “a life and death matter”.

Sudan’s silent detractors

While international attention has focused on this war of words between Egypt and Ethiopia, very little consideration has emerged over the concerns of Sudan’s citizenry. In February, dozens of activists coming from the Fung Province, Blue Nile State Peace Activist Group protested in the capital over the GERD negotiations in front of the cabinet and presidential palace. Many of those who protested in Khartoum did so from experience – having been displaced by another dam – the Roseires Dam in Blue Nile State, activist Gasam Saber told Ayin. “We have had a hard experience with dams [in Blue Nile]. The Roseires Dam displaced many people and destroyed their lands – people are still suffering from the environmental effects and this dam is very small in comparison to Ethiopia’s Renaissance Dam next door.” According to a 2017 report by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, dams have displaced roughly 80 million people worldwide.

The Renaissance Dam protestors issued a series of demands to the government, including greater transparency in the negotiation process, more public participation and compensation for Blue Nile residents as well as the removal of the minister of water and irrigation, according to a statement seen by Ayin. Saber believes the Renaissance Dam, based only 14 kilometres from the border of Blue Nile State, will displace residents and destroy farmland by removing vital silt deposits. Accustomed to civil conflict in the restive state, Saber says, “now we will be displaced by environmental affects,” adding that the dam is built near a volcanic area and could collapse in the future.

The Minister of Water and Irrigation, Professor Yasser Abbas, disputes these claims. The minister told Ayin that the dam is based over 540 kilometres from the nearest volcanic activity and was built using the latest technology with safety measures in place. Instead, Minister Abbas says the dam’s opponents do not rely on any scientific studies and, instead listen to those opposed to the country’s development. In response, Saber and the other activists accuse the minister of denying the public information concerning the levels of water and electricity Sudan is expected to receive once GERD is operational.

Even fellow members of the government decry the lack of transparency in the GERD negotiation process. Boshra Hammed is the Secretary General of the High Council for the Environment, a governmental body that coordinates activities with the water ministry. Hammed fears the dam will increase humidity and rainfall in the Blue Nile region. Like Saber, the environmental chief says the dam will remove much-needed silt from agricultural lands near the river. “The soil of the country will be very poor as the physical and chemical properties of the agricultural soil will change,” Hammed told Ayin. But these environmental concerns have never been raised, Hammed says, since no study gaging the potential environmental risks in the dam’s construction has taken place. Hammed says he would be more supportive of the minister “If the dam issue was discussed wildly in public, but instead we wake up in the morning and find that the dam is a reality.”

More water, power for Sudan?

In response, the minister says there are no studies indicating climate change from reservoirs. “The fears of those environmentalists come from reasons best related to them and not based on scientific fact,” he told Ayin. Both the minister and Hammed agree that GERD will improve water availability for Sudan throughout the year. “It will improve water availability in Sudan and allow farmers to farm at any time in the 12 months and grow varied crops,” says the Highs Council Secretary, “unlike the situation now where water is only available for farmers in the winter and summer months.” Geologist and Dean of the Faculty of Earth Sciences at the University of Red Sea State, Kareem Aldeen, also supports the dam’s construction. “The dam has a lot of benefits for Sudan,” Aldeen said. “We can get electricity and better irrigation for lands in west and east of the Blue Nile where there are big agricultural spaces.” According to the dean, the dam will provide Sudan with an “agricultural renaissance” in several cities: Sanaar, Damazin, Kosti and the Al-Gezira region.

But others are not convinced.

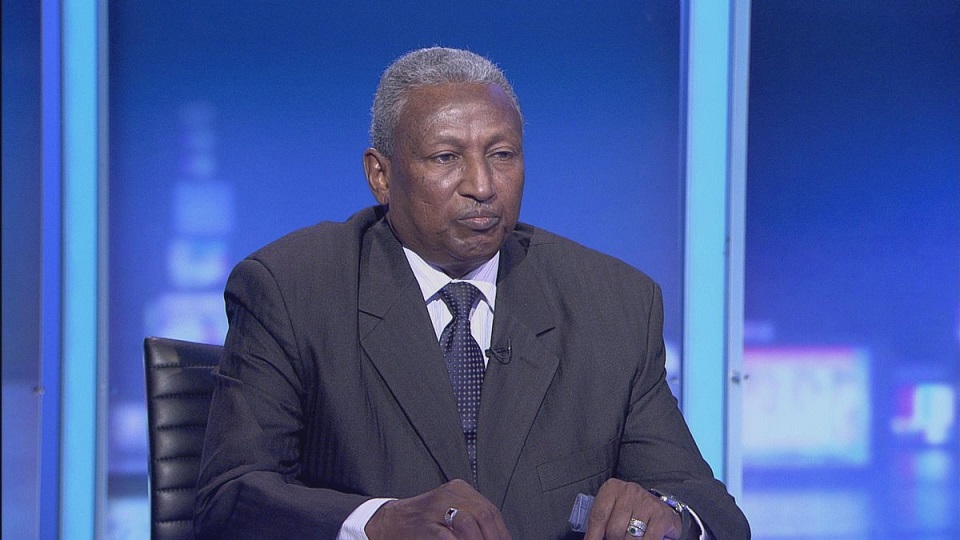

Dr Ahmed al-Mofteey, water expert and former rapporteur for Sudan’s High Committee of International Waterways believes there is a lack of clarity regarding water availability vis-à-vis the dam. “I think the minister is wrong about water availability for Sudan, each side presents a different scenario and in any of these cases, Sudan’s water will be reduced.” Sudan may be denied any surplus electricity as well, al-Mofteey told Ayin, given Ethiopia’s needs. “Now it appears the electricity generated will only be enough for Ethiopia.”

Without providing scientific evidence to allay public fears, opinions regarding the merits and disadvantages over the Dam’s impact on Sudan remain polarised. The current tripartite negotiations over GERD lack any confidence-building measures for the Sudanese public, who have already experienced their fair share of negative consequences from dam constructions, says economist and columnist Dr Faisal Awad. “The [negotiation] document for the Renaissance dam does not contain an y provisions that explains the benefits of the dam for Sudan, including the electricity percentage and cost,” Awad told Ayin. “Perhaps even more frightening, there is no provision for compensation in the event the dam causes damage.”

While Ethiopia remains committed to complete the dam’s construction and Egypt is determined to slow the process down, Sudan must insist on more transparency and information before committing further. “I think the Sudanese people are unaware about the dam,” said Dr Ahmed al-Mofteey, “after a year, when the dam’s effects appear on the ground, people will know the truth – protests will be across the country, since this dam could sink us.”