Massacre in Ramadan: The June 3 military assault on Sudan’s largest protest site

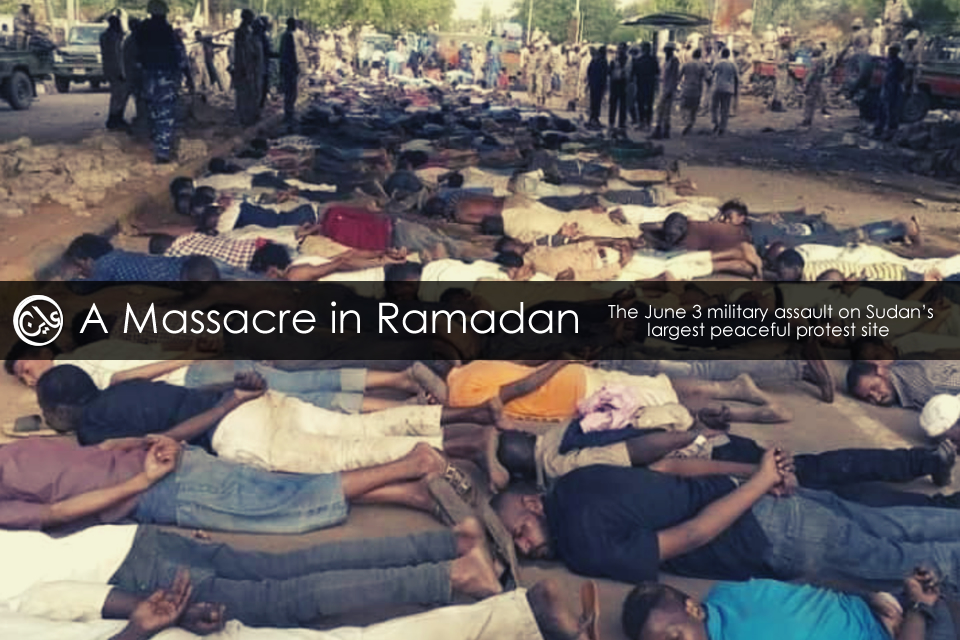

“They are shooting at us! They are shooting at us!” an unknown protestor is shouting while running for his life along University Street. It’s early morning on 3 June when clouds are still permitted to permeate Khartoum’s normally blistering sky and paramilitary units are firing indiscriminately across the once sleepy scene. Fellow protestors are pulling injured bodies from makeshift tents where the demonstrators would sleep a few hours at the former sit-in site outside the army headquarters. Others bodies can be seen lifeless while colleagues bravely attempt to reach them despite bullets flying overhead. It was the last day for the Holy Ramadan celebrations and the eve of Eid. No one in Khartoum could celebrate.

On 3 June, security forces from the Transitional Military Council surrounded the sit-in protest site, hurling tear gas, beating protestors with reeds, whips and firing live bullets in the early morning hours. The Central Committee of Doctors estimates around 118 people were killed in this attack along with 784 wounded with the caveat that the number may be higher, the committee reported, as there are still many people unaccounted for.

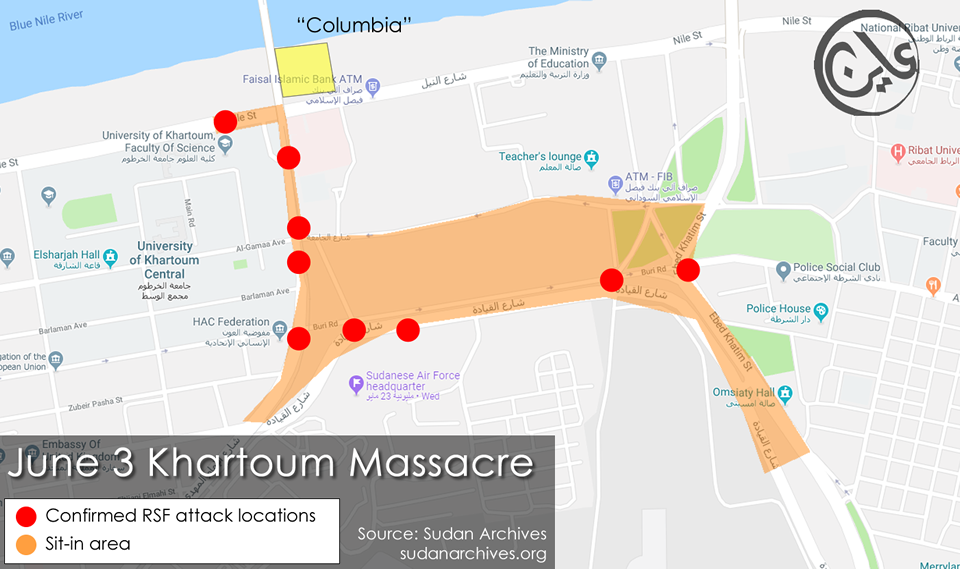

Based on eyewitness accounts and crowdsourcing research, the targeting of the protestors was a planned attack designed to clear the protest site and to quell any further civic action. Security forces under the command of the Transitional Military Council (TMC) attacked the protestors at nine strategic locations surrounding the former protest site, effectively blocking any escape routes from an indiscriminate attack against civilians. In one day, after the deadly attack, the area outside the army headquarters where thousands of demonstrators had occupied for almost two months, and eventually ousted former president Omar Al-Bashir in April, became void of any signs of life.

Premeditated

The attack was not the first of its kind since the protest began but certainly one of the most deadly massacres to take place in the capital, Khartoum.

Authorities launched at least seven large scale attacks on protestors between 6 May and 3 June, in each case live ammunition was used. According to the Central Doctor’s Committee, a minimum of four deaths and twenty injuries took place during these attacks. Signs the TMC Deputy and Rapid Support Forces militia leader, Lt.-Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Daglo (aka “Himmedti), would target the protestors can be heard as far back as April. The commander of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a re-branded version of the notorious Janjaweed militia, spoke to his troops on 9 April claiming the protestors were “looting” the area and they had a “duty” to protect civilians. When the protest movement expanded the sit-in site closer to Blue Nile Bridge in an area unofficially termed “Columbia” in May, the TMC made repeated threats to clear the area, claiming it was inhabited by drug peddlers. Authorities attacked the location twice, in one incident shooting dead a pregnant woman. On 30 May, RSF’s Major-Gen. Othman Hamed accused the sit-in site, and Columbia in particular, of attracting prostitutes and drug dealers. The sit-in “has become a hub for all kinds of criminal acts, and has become an unsafe place and a threat to the revolution and revolutionaries, and a threat to the national security of the state,” he said in an evening public address. “Therefore, we at the Rapid Support Forces in coordination with other security forces who are responsible to restore the safety of the citizens to carry out legal procedures to stop these violations and this behaviour.” This announcement, among others made by the TMC, acted as a justification for the 3 June attack.

Ayin’s video report on June 3 covering the massacre

A Sudanese security expert speaking on condition of anonymity for security concerns told Ayin Saudi Arabia and its regional allies accepted and supported the TMC’s decision to clear the protest site. The expert along with news reports suggest the plans to destroy the protest camp were discussed during May visits to Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Egypt by the head of the TMC, Lt.-Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan. Further, Saudi and Emirati cargo planes landed at Khartoum airport in early June shipping military vehicles for the TMC, Sudanese air pilot Siddig Abufawaz told the New York Times.

Ahead of the attack, the Sudanese foreign ministry issued an alert to all foreign embassies as well as international organizations operating in Sudan to avoid the sit-in premise and all protest sites across the country “for the sake of their own safety and security.” The TMC had prevented a number of local television stations from attending the sit-in and covering events near the time of the raid, according to Abdul Salam Mendas, a protestor and victim of the 3 June attack.

As a final measure, potentially to conceal the attack, the TMC shuttered international broadcaster Al-Jazeera without explanation just three days before launching the raid on the protest site. “The network sees this as an attack on media freedom, professional journalism, and the basic tenets of the right for people to know and understand the reality of what is happening in Sudan,” the network said in a statement.

While evidence suggests the TMC was opposed to the protest sit-in site and attempted to collect support to remove the demonstrators, no one except the perpetrators could predict the level of violence that would follow.

At around 4:45 am after the Muslim call to prayer, the security forces under the TMC launched their attack against the protestors at the sit-in site, targeting those near Blue Nile Bridge and the Sama Resort along Nile Street, according to eyewitness accounts and crowdsource data. While the security forces started their assault in this northwestern corner, they soon blocked protestors from escaping the sit-in area targeting them further south along University and Buri streets on the western side and along Buri and Ebed Khatim streets on the eastern side. The majority of the forces entered the sit-in from the southern side near the entrance to the military headquarters, Mendas said. Interestingly, the security forces did not target the “Columbia” area despite it representing the original excuse by the TMC to clear the protest site.

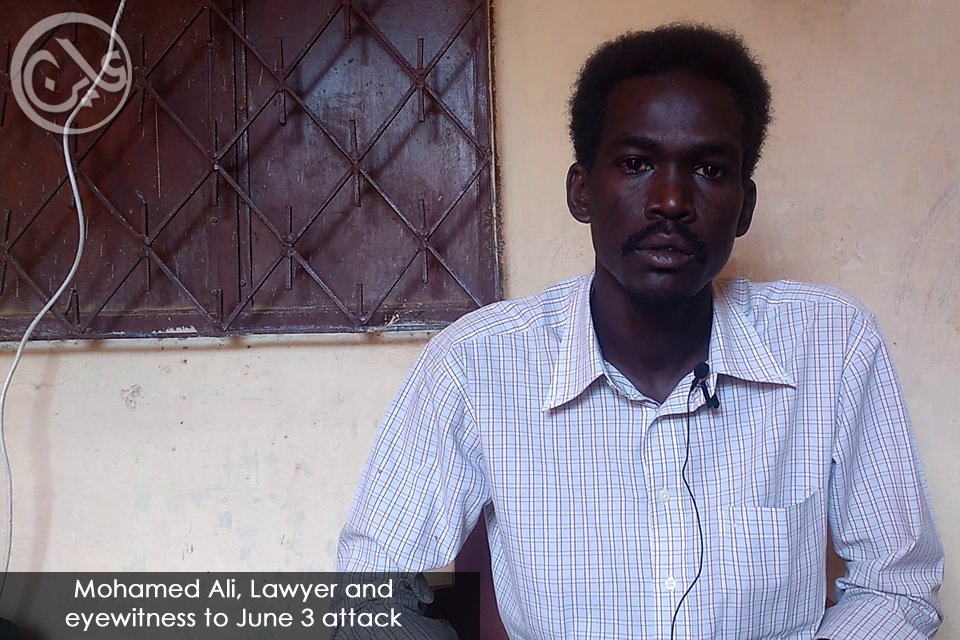

Lawyer Mohamed Ali headed over to Nile street after hearing reports that security forces were trying to break up the sit-in – having no idea what level of force the TMC had set up. “A lot of vehicles were lined up and the police were carrying shields, behind them were more forces carrying weapons – these were the RSF and they attacked us.” Protestors starting chanting “peace”, Ali said, but there was no response from the security forces before they rushed the barricades to attack demonstrators.

While most eyewitness accounts confirm seeing police and RSF forces attack the sit-in, it was not always easy to determine who exactly attacked them. The police, for instance, were wearing new uniforms but wore slippers and sandals -as if hastily prepared. Whomever they were, few protestors could remain in one location to find out. Bullets flew everywhere, Ali said, “if anyone threw a rock at them [security forces], they get a bullet. We kept moving from one place to another and jumping one wall after another — but we suddenly found out these forces were coming and firing from all directions.” Mendas, who attempted to film a live Facebook feed during the attack, told Ayin that the TMC had snipers positioned above in the buildings. “They were hitting inside the courtyard of the sit-in, targeting people who were filming and broadcasting or carrying a camera.” The security forces also conducted a looting spree within the sit-in courtyard, he added. “If you fall they take what’s in your pocket. When near the [protestor’s] tents, they would enter the tents, take everything inside and then burn the tents.”

Wifaq Ahmed Abdullah was volunteering at Ashamna, an orphanage project based at the sit-in site, when the security forces raided the tent where she was working and witnessed them burning the tents firsthand. “You either got hit with bullets or by their Land Cruisers,” Ashamna added, referring to large numbers of the security-owned vehicles, all void of license plates. The security forces, wearing RSF and police uniforms, asked her “You want a civilian [government]? Look what the civilian [government] got you.”

Hospitals Targeted

Even wounded protestors who managed to find treatment were not safe. According to eyewitnesses and news reports, security forces targeted hospitals that treated some of the countless wounded protestors. Security forces fired live ammunition within the three hospitals: East Nile, Royal Care, and Teachers Hospital, according to medical sources and eyewitnesses. Nazim Siraj, an activist who helps medical support coordination among the protestors, told Ayin security forces comprising of police and RSF units surrounded Royal Care Hospital and Teachers Hospital, ordering patients and medical workers to evacuate the premises. One patient within the intensive care unit at Teachers Hospital died in the process, he added.

A doctor, preferring anonymity for security reasons, tried to treat patients at Teacher’s Hospital, despite getting injured himself. “When we got to the hospital, no one was hit by a rubber bullet, they were all hit with live ammunition,” he said. Security forces also entered Imperial Hospital and threatened one doctor who attempted to prevent their entry with a gun, said Hamdan Mohammed Ahmed, a protestor who injured his head and broke his hand during the attack.

Dumped and disappeared

While the doctor’s committee has been able to confirm 118 deaths from the 3 June attack, there are indicators the number could be higher as bodies are recovered from the Nile. Eyewitnesses and verified photos reveal military pick-up trucks carrying bodies with cement blocks tied to them prior to dumping in the Nile. Other bodies have been identified in mass graves far from the protest site, according to the doctor’s committee. The Committee said 40 bodies were recovered from the Nile. One of those recovered was the body of Amal Agus, a female street vendor and member of the Cooperative Federation of Women Food and Beverage Vendors, according to a statement. The women’s food and beverage union reported that five women tea sellers are missing since the attack. To date, dozens of protestors at the sit-in on that fateful 3 June are still missing according to an ongoing outcry of social media messages where family and friends post messages, often with photos of their missing loved ones. Missing individuals such as Hassan Osman Abushanab have been reported through social media, as well as a Facebook page dedicated to missing reports, which is run by credible activists.

Sexual harassment, assault

A vetted social media photo taken on 3 June depicting an RSF soldier hanging women’s underwear off of a cannon has gone viral with several sources confirming that cases of sexual assault took place. The level of these assaults, however, is difficult to ascertain with some sources estimating around 12 while others report as many as 70 cases. According to the pan-African think-tank, the Africa Centre for Justice and Peace Studies (ACJPS), some victims were raped inside a clinic attached to Khartoum University where they had run for safety from security officers.

The Ahfad Trauma and Counseling Center received seven cases of rape incidents from the 3 June attack, according to physiologist Suleima Sharif. Many of the protestors told the center security forces threatened to rape them during the attack. Security forces would threaten women and sometimes men with sexual assault if they did not agree to the military and Himmedti to rule Sudan, Sharif said. The repeated threats “seem like a message to prevent women from demonstrating against the TMC,” Sharif said. The threat of rape is very effective in the Sudanese context, Sharif said, since sexual intercourse outside of marriage is a source of great shame for Sudanese families. “I saw this for myself -how they [security forces] were harassing women, threatening rape, they did this to me as well.”

Hide the evidence: cutoff the world

After the onslaught the TMC cut off signals to telecommunication companies Zain and Canar, effectively silencing all reporting on the attack. While the death toll rose and attacks on citizens across Khartoum continued after the attack, the TMC cut off another provider, Sudani, on 10 June, instigating a near-total blackout of connectivity for the majority of citizens. The following day, TMC Spokesman Shams al-Din Kabashi admitted that the TMC cut the Internet, stressing it will remain off for a long time since connectivity constitute a “national security threat”.

Ambiguous aftermath

Despite several eyewitnesses laying blame for the massacre at the doorsteps of the RSF and Himmedti in particular, the TMC and militia commander denied responsibility. At first, the TMC refuted it had ordered the violent dispersal but incongruously said it had ordered a purge of the “criminal” area known as Columbia –an area that was left untouched during the attack. Ten days after the attack, the TMC finally confessed to launching the attack. “We ordered the commanders to come up with a plan to disperse this sit-in,” said TMC Spokesman Shams al-Din Kabashi, “They made a plan and implemented it […] but we regret that some mistakes happened.”

The same day, the TMC pledged it would implement an investigation into the deadly raid and detained around 400 RSF members at Suba Prison in Khartoum, ACJPS and Sudan’s state news wire reported. The arrests were only temporary, however, and posed to appease the public and international community, the centre said.

Despite these acknowledgements, Himmedti claimed on 20 June the “mastermind” behind the attack had been “identified” but did not reveal the identity. The militia leader alleged in a military-backed women’s rally in Khartoum that perpetrators of the attack were wearing the RSF uniform and using fake IDs. “We arrested a general yesterday for distributing IDs of the RSF,” he said, “Anyone who had crossed his limits whether they are from the military or civilians, I swear to God, will stand trial.”

Ayin’s video report on June 14 covering the aftermath of the massacre where the RSF attacked Khartoum neighborhoods, far beyond the borders of the sit-in

While we may never know who exactly within the TMC ordered the attack, the nature of the assaults, rapes, looting and then finally denying culpability, mirrored the tactics traditionally used by the RSF in Darfur, South Kordofan and Blue Nile States. “The 3 June massacre in Khartoum felt like a deja vu,” wrote political cartoonist Khalid Albaih. “Over the past eight years, we have seen Arab tyrants bent on keeping power at any cost taking countless lives in the same exact brutal manner in plain sight of the international community.”

What is clear is the TMC’s rejection of the power-sharing agreement for a transitional period they had ascribed to prior to the attack. After the 3 June raid, all former deals were conveniently scrapped. In May, the TMC and opposition agreed that a technocratic government appointed by the Freedom and Change coalition would administer the country during a three-year transitional period and would appoint 67 percent of the 300-member parliament. Himmedti repeatedly voiced his disdain for this agreement before 3 June, taking particular offense for the opposition-led legislative appointments that could effectively enact laws dissolving armed groups under his control. “How can you have 67 percent? They want 67 percent and the whole executive council,” he said in a speech with the police administration in Khartoum. “The goal of these people [Freedom and Change coalition] is to rule, and we go to our barracks,” he told the police. “Instead of dying with disgrace and letting these people scheme on us and then create our laws, it’s better we die today rather than tomorrow.” The deadly raid cleared up the protest site and swept aside all previous political agreements. Madani Abbas Madani, a member of the Freedom and Change Movement, agrees. “The military council has dismantled the sit-in to create a new reality that allows the TMC to renounce the previous agreements,” Madani told Ayin. “It has been clear since the signing of the agreements.”

Picking up the pieces

The TMC dispersal of the sit-in site may have destroyed the crowning symbol of Sudan’s revolution and call for civilian rule, but the peaceful protests –including the nationwide strikes–are set to continue. “The mass movement did not stop at any moment,” claims Madani, “all the peaceful tools that achieve the objectives of the revolution will [continue to] work.” The 3 June attack also dispelled any smattering of trust between the TMC and the Freedom and Change coalition but it has strengthened the opposition’s conviction to continue to call for civilian authority without compromise, Madani said. “Any agreement that does not achieve this will be rejected by the forces of freedom and change,” he added. Repeated attempts to contact TMC Spokesman Shams al-Din Kabashi were left unanswered. The Sudan protestors are already preparing another mass demonstration for Sunday, 30 June, to demand the handover of power to civilians. The protest commemorates the 30th anniversary of the coup that brought Omar Al-Bashir to power, toppling Sudan’s last elected government. The TMC may have broken the sit-in site but the public’s determination to continue calling for political reform seems, at least in the near future, steadfast and intact.