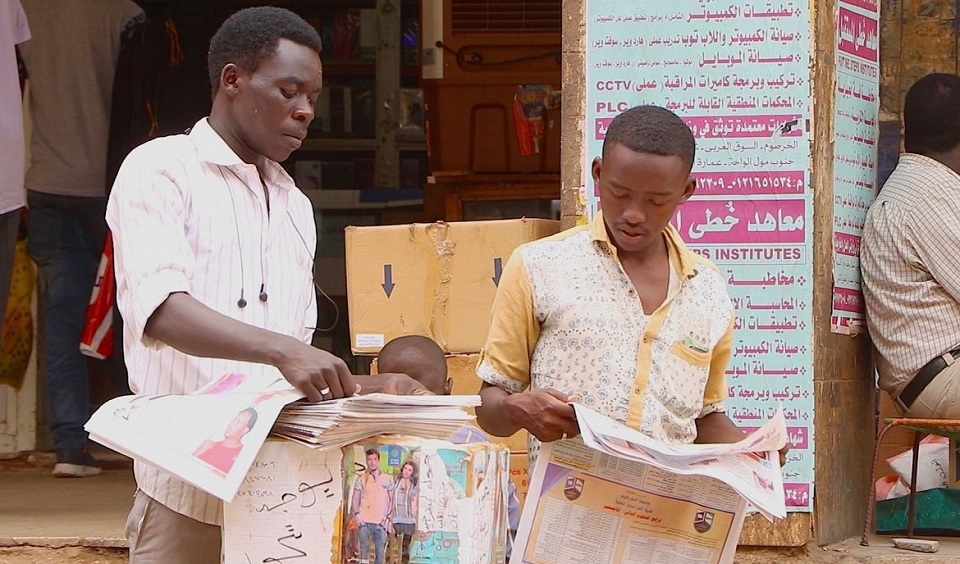

Sudan’s press, from repressed to self-repressed

Sudan’s press is undergoing several reforms in a spirit of increasing openness under the new administration, but the vestiges of a past, censored press that supported the former regime remain.

According to the secretariat of the independent Sudanese Journalists Network, Hassan Barakieh, the media scene has undergone some noticeable changes since the former regime fell, most notably the absence of direct and indirect censorship by the security forces against newspapers. Security forces under former president Bashir confiscated 34 newspaper print runs and arrested 66 journalists in the first month of the revolution, according to the press freedom organisation, Reporters Without Borders,

Past authorities also used economic measures to indirectly control the press by either offering or removing much-needed advertising revenue through the recently dissolved Al-Adan Distributing Company, Barakieh added. “In the past, it was known that the security apparatus was the main guide for all media operations in the country, especially the government-related press institutions such as the Press Council and the Union of Journalists,” he added.

Media reforms

Information Minister Faisil Mohamed Saleh said a workshop would be held on Monday with 150 experts to review and reform Sudan’s media policy to ensure the country has a free and transparent press. The government has also given a timetable for anti-press laws to be amended within a six-month period.

In last month’s International Book Fair, attendants were surprised to see for the first time a booth promoting the work of banned religious leader Mahmoud Mohamed Taha, founder of the Islamic Republican movement. During the inauguration of the Fair, Information Minister Faisil Mohamed Saleh assured attendants that no restrictions on books – whether religious or political in nature – would take place at the annual event. The remarks represent a break from the past where books were either banned or seized by authorities under the former ruling National Congress Party (NCP).

In September, the Sovereign Council also wrestled control over the Telecommunications and Post Regulatory Authority from the Ministry of Defence. Given the ministry’s links to the former regime under president Omar Al Bashir, the move may curb a long tradition of online disinformation by NCP cadres. Since 2011, the security service under the NCP operated the ‘Cyber-Jihad Unit’ designed to infiltrate online dissidents to the former ruling party and spread disinformation.

The unit was particularly active during the revolution and did not act alone. The Russian firm M-invest, for instance, developed various strategies to delegitimise protestors –everything from fabricating evidence of arson attacks against mosques and hospitals to stealing grain from public stores. One suggested strategy that was applied by the former regime was to use “extensive media coverage of the interrogation of detainees, where they admit they arrived to organise civil war in Sudan.” This latter strategy was applied by the former regime in December 2018 when security forces detained and tortured university students from Darfur in an attempt to force them to falsely admit to working with Israeli secret services to sabotage the government.

Later in September, Prime Minister Abdullah Hamdok broke from the past by signing the Global Pledge to Defend Media Freedom and declared at the United Nations General Assembly that, “never again in the new Sudan will a journalist be repressed or jailed.” On Saturday, during the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists, Minister Saleh reiterated this statement pledging, “The government will prevent any kind of harassment, abuse threats or pressure in any form against journalists. Crimes against journalists by individuals or groups will be dealt with swiftly.”

Bashir’s long-term footprint in the media

Despite these measures, the presence of media houses – whether directly or indirectly aligned to the former NCP regime — are still major influencers to the information narrative for Sudan.

According to the information minister, they are taking measures to dismantle media houses set up by the security forces and nine other companies aligned to the former ruling party. “With the security forces we began the process of dismantling its media outlets for its competence now is limited to gathering information only,” Saleh told Ayin. But dismantling former mouthpieces of Bashir’s government may not be enough. The real challenge, the minister says, is changing the “censored mind set” that was prevalent among the staff in the General Corporation for Radio and Television for the past 30 years. Staff were hired for loyalty, not critical reporting.

The minister told Ayin they are setting up new guidelines and replacing the senior management at the state broadcaster in an attempt to set up an independent, professional body. By mid-September, the government replaced Ismail Eisawi as director of the Sudanese Radio and Television Corporation with Ibraim El Buz’I, a former radio producer. This decision followed a plaintiff filed by the Democratic Lawyers Alliance in September against the state broadcaster over two films produced by the state broadcaster in June, ‘Bats of Darkness’ and ‘Khartoum Wails’, that the lawyers say depicted the demonstrators in the revolution as murderers and saboteurs.

While the government has the authority to reform the state broadcaster, a huge consortium of media houses with close affiliation to the former regime remain in circulation. According to Minister Saleh, 90% of newspapers published in Khartoum opposed the revolution with either direct or indirect links to the former ruling party.

It is not only the newspapers.

Barrakieh told Ayin security forces aligned to the NCP still own and control a key printing press in the capital where 80% of the newspapers in Khartoum are printed. “The urgent demand for journalists is to dismantle this structure.

Barrakieh told Ayin security forces aligned to the NCP still own and control a key printing press in the capital where 80% of the newspapers in Khartoum are printed. “The urgent demand for journalists is to dismantle this structure. The government has already begun the process of dismantling it, but with slow steps, we need to accelerate the pace until we reach the required level of press freedoms and resolve all restrictions on these freedoms,” he added.

Some media houses owned by the NCP are attempting to hide their links by transferring ownership to others, Saleh told Ayin. One example being Ashrooq TV that routinely acted as a mouthpiece for former president Bashir and was funded by Sudanese taxpayers. “Ashrooq is not the only one,” Minister Saleh said, “Eight other bodies are being scrutinised and shall be revealed later.”

A revolutionary conundrum

Despite the prevalence of both private and state media houses that oppose the revolution and the newly formed government stemming from it, there is little the information minister can do about it. After pledging a free and open media without state repression, the minister can hardly target these pro-NCP outlets. “State intervention cannot be done except with an oppressive and this is not acceptable. It is as if I am being asked to call on the security apparatus to stop these writers from writing; something that is the complete opposite of the revolution and the freedom we advocate.”