The former regime is back – Burhan reinstates the National Congress Party

25 May 2022

As Sudanese continue street protests against the military takeover and political parties have commenced an international-brokered dialogue with the military, the former regime is surreptitiously regaining power.

Since January, Islamic leaders linked to the former National Congress Party (NCP) have been released while others have been re-instated into civil service positions across the country.

Leaders of Sudan’s October 2021 military coup have released several influential Islamic leaders linked to the NCP including Ibrahim Ghandour, former NCP chairperson and two other NCP leaders, Anas Omar and Kalaleldin Ibrahim. The top NCP leaders and others have been cleared of charges of undermining the constitution, financing terrorism, and plotting the assassination of former premier Abdalla Hamdok, lawyer Abdelrahman Al-Khalifa said.

Upon Ghandour’s release in April, a coalition of eight Islamic parties signed a new alliance under the moniker “The Broad Islamic Current”. “One of the goals that we look forward to from this alignment is to ensure that the values of religion are applied to all aspects of life and return in a comprehensive and integrated way,” the new political group said in a statement during their launch in April.

In parallel, coup leader Lt.-Gen. Abdelfattah al-Burhan reappointed certain Islamic fundamentalists and NCP members to sensitive positions within security institutions. Burhan promoted Lt.-Col. Mudathir Osman as his office secretary in the army headquarters – the son-in-law of the fugitive Islamist leader, Ali Karti. Previously in hiding, Karti is now a public figure in Sudan and is expected to feature in a television interview in the near future.

Burhan also appointed Husham Hussein, the former office manager of the NCP’s security service, as the deputy director of the current security service –the General Intelligence Service. Hussein played a pivotal role in the pro-military protests that took place before the coup and funded the pro-coup “palace sit-in” via his ownership of the Muqrin Oil Company. The NCP stalwart is also the main supervisor of the Central Reserve Police, a security unit routinely linked to the repressive measures used against the anti-coup demonstrators that have led to at least 96 deaths since the 25 October military coup, according to medical reports.

Courts as a conduit for NCP’s return

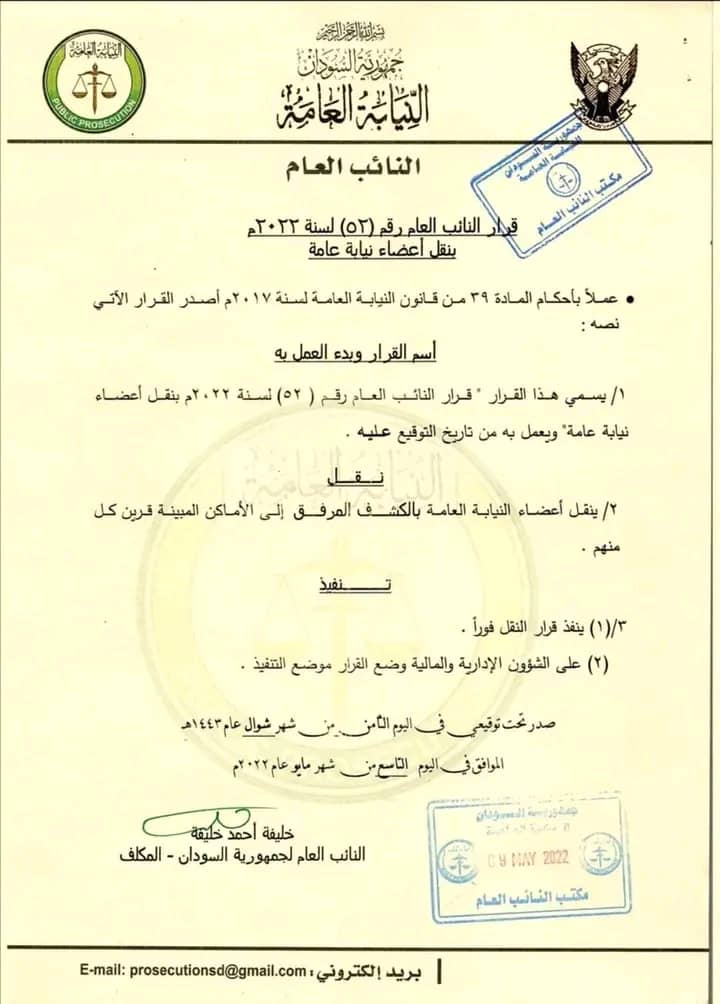

The return of NCP cadres and Islamic parties to the political scene is largely connected to key appointments in the courts, analysts say. While some in the judiciary have actively opposed the coup, Burhan’s appointments of two well-known Islamists and NCP members: Chief Justice Abdelaziz Fathal al-Rahman and Public Prosecutor Khalifa Ahmed Khalifa –have paved the way for the NCP’s return to politics. Khalifa was a prominent NCP member and President of the Bar during the former regime under ousted President Omar al-Bashir. Khalifa was also a member of Bashir’s defence committee against corruption charges.

Other prosecutors from the former regime have also been re-instated, according to official documents seen by Ayin. The head of commercial prosecution is now run by Al-Fateh Muhammad Tayfur, a former public prosecutor during Bashir’s rule who was assigned under the Darfur crimes prosecution team to dismiss countless human rights cases against the then government. Prominent NCP members and Islamists, Yasser Abdel Hamid and Mahmoud Mahdi Ahmed, are now reinstated as Heads of Prosecution for crimes against the state and narcotics, respectively.

In turn, independent prosecutors installed during the transitional period have been re-assigned to lesser, regional stations. One renowned prosecutor in charge of looking into cases of killed anti-coup protestors, Mohamed Al-Safi Mohamed, has been transferred to Blue Nile State. Prosecutor Ali Amir Hamad, who used to investigate reports of gold smuggling, has been transferred to South Darfur State. While prosecutor Suhaib Abdul Latif, the rapporteur of the commission set up to investigate the 3 June 2019 attack on protestors, was transferred to Northern State. In a recent press conference, the head of the committee, lawyer Nadib Bilal, said they were forced to suspend their work due to interferences from the military authorities.

According to a report by Africa Intelligence, a pan-African, independent media platform, Islamists are using the justice system to release their supporters, reclaim their property, and intimidate opponents. It is a tried and tested tactic, the report says, that Islamists used in the early 1980s and after Bashir’s coup in 1989. These judicial manoeuvres have resulted in the return of 102 diplomats, including 48 ambassadors, 35 junior diplomats and 19 administrative staff to the foreign service.

In some cases, loyalists to the NCP have been given high-ranking positions without the appropriate qualifications. A similar trend was identified at the Ministry of Labour in 2020 – whereby employees from the former regime were hired for loyalty rather than academic qualifications. According to employment records seen by Ayin, nearly half (49%) of employees at the ministry were not academically qualified for the roles they held.

The Dismantling Committee…completely dismantled

While the courts are releasing members of the former regime in record numbers, those who helped arrest them before last October’s coup are in constant fear of incarceration. The Dismantling Committee was set up during the transitional period in Sudan to remove NCP-affiliated organisations and individuals. On the eve of the military coup, however, security forces raided their offices and suspended all of their activities.

According to a leading member of the Dismantling Committee, removing the Committee was one of the main reasons that led the military leadership to launch the coup in the first place. It is an assessment Sudan analyst Alex de Waal agrees with. The Dismantling Committee “was not only exposing and uprooting the network of companies owned by the Islamists forced out of power in 2019,” de Waal said, “but also the tentacles of the commercial empires owned by senior generals.”

In March, security forces detained the senior leadership of the Dismantling Committee for six weeks on alleged corruption charges. “We do not feel safe because we can be arrested again at any time,” the committee official told Ayin. Since their case files remain open, he says, they can easily be re-arrested. For over five months, security forces have detained Lt.-Col. Abdullah Suleiman, a police delegate assigned to the Dismantling Committee assigned to guard recovered assets.

Since the coup took place, 90% of the decisions issued by the Committee have been overturned and retracted, the official said, “either by direct decisions from the coup authority or by members of the former regime in the judicial system.”

Sudan’s civil service – back to Bashir

Local officials working within Sudan’s government told Ayin they have noticed large numbers of former NCP cadres re-entering the workforce. For example, the Khartoum Refinery Company, a parastatal linked to the Ministry of Petroleum, had 48 employees linked to the NCP removed during the transitional period. But according to one official working at the company, 37 had returned by late April this year. “Immediately after the coup on 25 October, they [NCP cadres] returned in groups,” the official told Ayin. “They returned with their full rights, even the salaries of the previous two years when they were absent.” Once former premier Abdalla Hamdok resigned in January this year, the only civilian representative within the military government at the time, supporters of the revolution within the civil service were removed and NCP members returned unopposed, the official said. Roughly 70% of employees at the Refinery belong to the National Congress Party.

The revival of NCP in politics and economic projects can be witnessed across the country.

Take, for instance, the “Kanaf Abu Namma” project in Sennar State. The “Kanaf Abu Na’ama” project, located in Abu Hajjar locality, is one of the most prominent producers of the “burlap” industry fibres used for burlap sacks. It is a government project allocated by the ousted regime for the benefit of investors, most notably businessman NCP member, Muawiya al-Barir.

However last year, the Dismantling Committee had decided to allocate the project to farmers in the region. A state member of the Committee, Khaled Al-Fadil, told Ayin that the project was allocated to local farmers but the military coup halted this and returned the project to businessman Muawiyah Al-Barir. On 18 May, military forces guarding the “Kanaf Abu Naama” project killed three civilians and wounded seven others after the farmers protested the reversal.

No choice

Given how unpopular the former regime is with the Sudanese populace and the junta’s Gulf allies who oppose Sudan’s return to Islamic fundamentalism, Burhan’s revival of the NCP appears self-destructive. But according to several political analysts in Sudan –-the coup leader had no other option.

Political analyst Khalid Mukhtar Salim says Burhan’s decision to ally with the Islamists represents the only option to curtail the revolutionary movement and the growing influence of his deputy, the Commander of the Rapid Support Forces, Lt.-Gen Muhammad Hamdan Dagalo (known by his nickname “Himmedti”). With the exception of Egypt, few international actors supported Burhan after the October coup, analysts said. Political support from the former regime represented the only means to maintain power amidst external and internal isolation from the international community and the Sudanese public alike.

With little political support from Burhan’s erstwhile regional Gulf allies, Egypt allowed Burhan to release certain Islamists, says Adel Bakheet, an expert in Egyptian-Sudanese affairs. “Cairo found itself between two options: extending support to Himmedti or returning the Islamists [to power] —so they chose the latter– provided that it was in accordance with a controlled process between Khartoum and Cairo,” Bakheet told Ayin.

Originally set up by Bashir as a tribal militia to counter Darfur rebel groups, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) under Himmedti has expanded its influence and wealth across the country. According to human rights activist Ahmed Othman, Himmedti and the RSF’s estimated net worth could be as much as US$14 billion –-largely through their control over Sudan’s gold mines and other assets. Such vast wealth could easily support Himmedti’s political ambitions for the presidency and further encroach control over Sudan’s conventional army.

Political analyst Ashraf Othman believes the army is trying to temper Himmedti’s expansion by widening its range of allies within the political arena. With few other options available, Burhan has entered a potentially uneasy alliance with cadres of the former regime.

It is an alliance that has, so far, failed, says members of Sudan’s civilian-led protest movement. Since October, Burhan has attempted to form a new government that the military could control. Instead, a political vacuum persists, and the economy continues to spiral downwards, directly affected by this impasse.