Less bread ahead – Sudan’s hunger gap predicted

24 June 2022

Musa Ali, a baker in Bahri, North Khartoum, is not looking forward to working in the days ahead. “The price of bread will go up –-my customers will not be happy—and [they] will blame me for something I cannot control.”

The Steering Committee of the Bakeries Union in Sudan expects a rise in bread prices. It is not surprising since the price of gas used for cooking fuel has recently jumped by 56% and the price of a jerry can of oil has also increased by 67 percent. In April, the price of wheat skyrocketed by 180% compared to the same period last year.

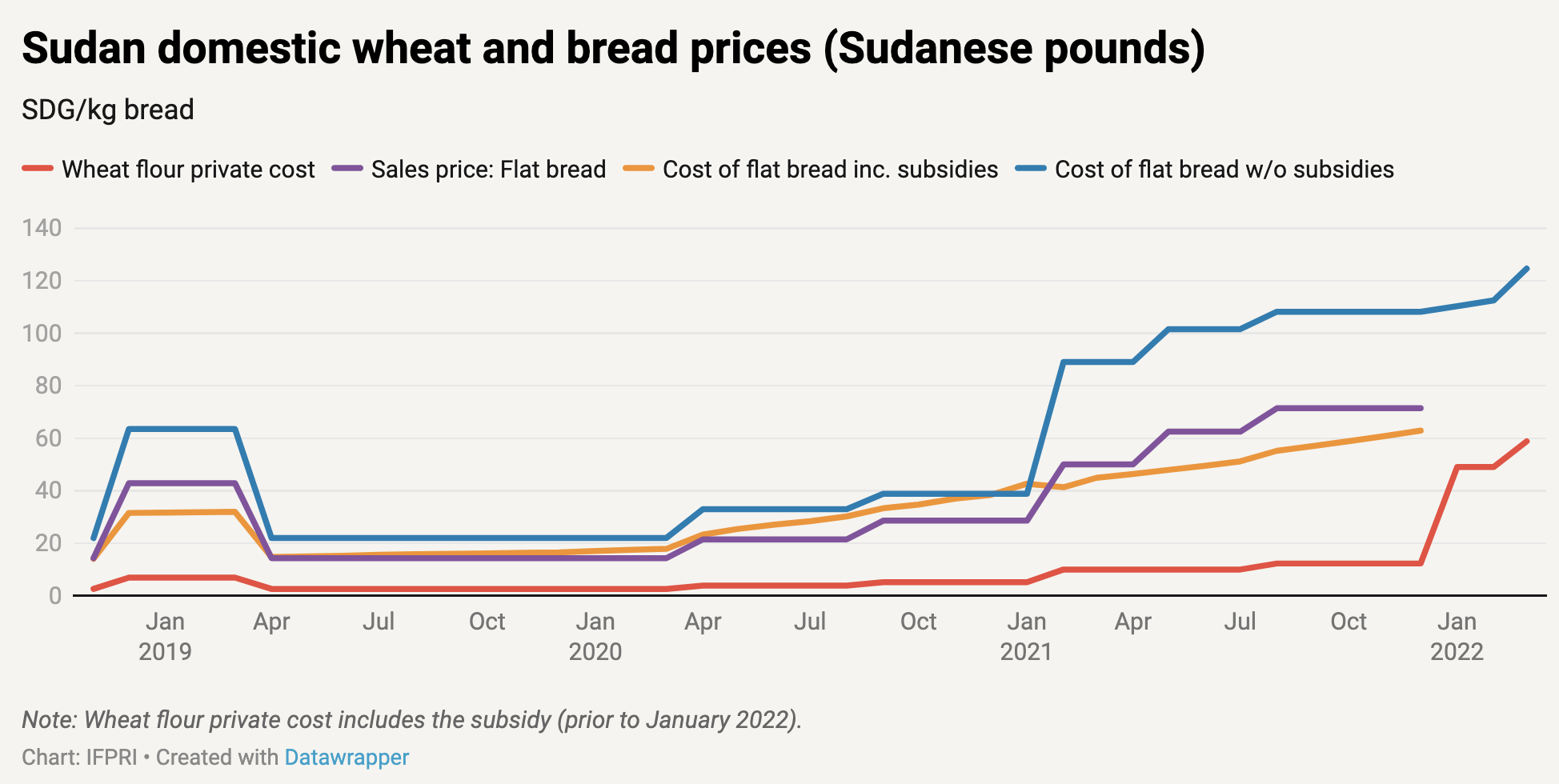

On 1 January, the government abandoned all forms of subsidies on wheat forcing milling companies to obtain grain in the higher-priced open market. Overall, between July 2021 and February 2022, the wholesale price of wheat in Khartoum rose by 60 percent.

This is particularly concerning for a country like Sudan where wheat consumption is roughly twice the world average. “Imagine, we used to sell bread for 25 [Sudanese Pounds] last year at this time,” Ali told Ayin, “now we are selling this same bread at twice the cost, for 50 Sudanese Pounds.”

Hunger ahead

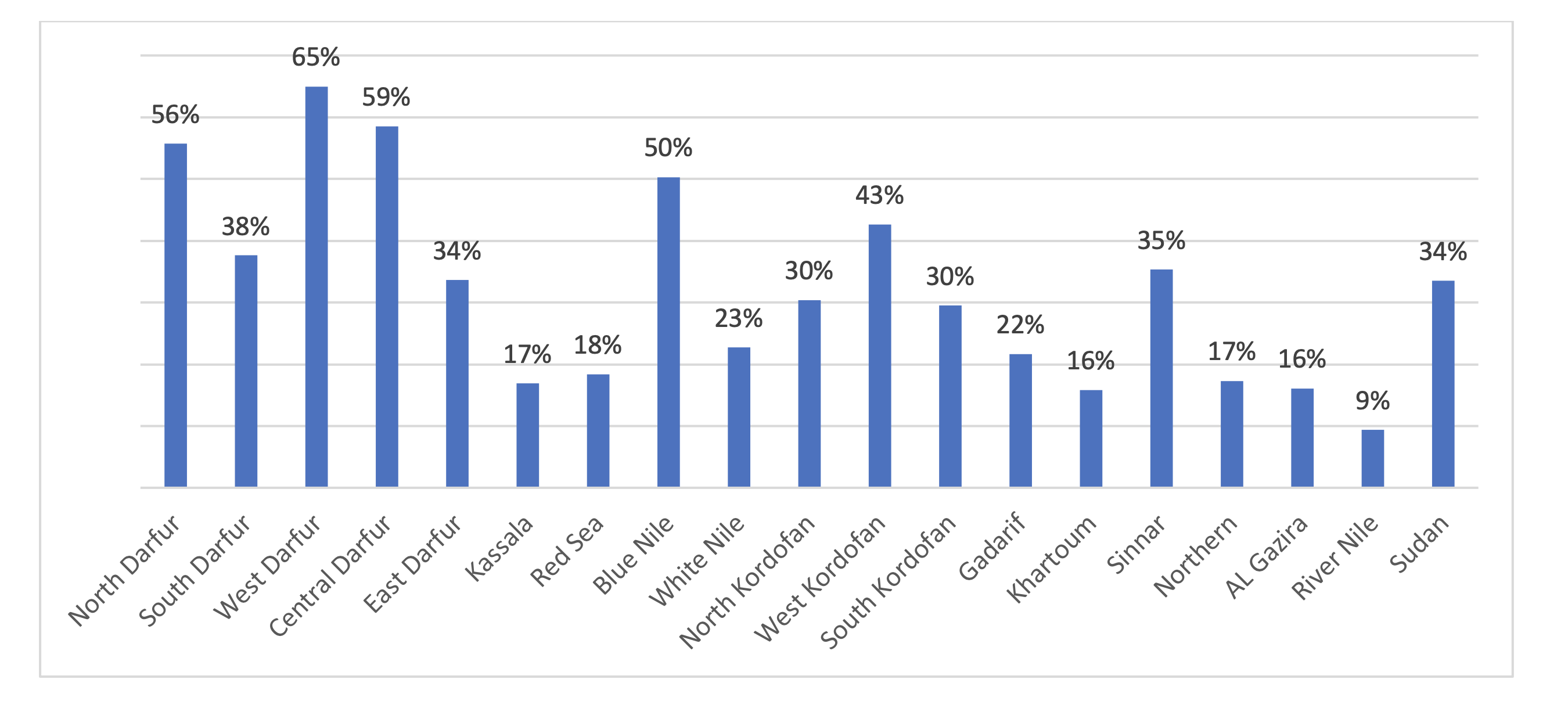

The United Nations predicts dire days ahead amidst high food prices and poor harvests with the Food and Agricultural Organization and World Food Program (WFP) estimating that 18 million Sudanese, over a third, will face acute hunger by September. “The societal impacts of conflict, climate shocks, economic and political crises, rising costs and poor crop production are driving millions of people into hunger and poverty,” said Eddie Rowe, WFP Sudan Representative.

A WFP report released this month states that food insecurity is present in all 18 states across the country –with the Darfur region being the most affected. Even more worrying, the UN’s children’s welfare agency, UNICEF, estimates that 3 million children are currently suffering from malnutrition, with 325,000 potentially fatal cases if treatment is not received.

According to the Famine Early Warning System Network (FEWS NET), a food security monitoring organisation, an estimated 600,000 tons of locally produced wheat is anticipated to be harvested this season, 33% less than last year’s production. The harvest will only cover roughly 23% of Sudan’s annual wheat demands, FEWS NET reports.

Farming at a “guaranteed loss”

Farmers in Sudan simply have not managed to produce as much this year as previously –partly due to unfavourable price conditions and, in other cases, perilous work conditions.

“Crop and livestock production has dropped by up to half in 14 states across Sudan when compared to the last five-year average,” said Farhan Haq, the deputy spokesman for the UN Secretary-General, Antonio Guterres.

To encourage farmers to sell their wheat harvest and build cereal reserves, the government set the purchasing price of wheat for farmers at 43,000 Sudanese Pounds (around US$ 94) per 100 kg sack in March this year-a significant increase from 13,500 Sudanese Pounds (roughly $30) per sack paid previously.

But farmers say this set price is still unprofitable due to high production costs and inflation. Last January, the Ministry of Finance raised electricity prices by 600% –jumping the cost of irrigation for small farmers immeasurably. Farmers also claim the government’s Agricultural Bank, which purchases and stores grains from farmers, has set impossible conditions upon them such as charging transportation and supply fees. Moreover, despite what farmers claim are unfavourable price conditions for purchasing wheat, agricultural officials say the cash-strapped government has been reluctant to fulfil these price payments.

The Minister of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Abu Bakr Al-Bishri stated in recent press statements that they have issued urgent directives to the Governor of the Central Bank to provide the required funds to purchase wheat from producers, appealing to farmers to be patient until the funds are available.

But many farmers have run out of patience and even the will to continue farming.

According to farmer El Jaili El Sheikh in Sennar State, crops have suffered from poor rainfall and, what he calls, insurmountable fuel prices, forcing most farmers into insolvency. Many farmers in Sennar, El Sheikh added, will not plant this season if diesel is not available and the Agricultural Bank will not adjust its debt payments.

The Director of the Agricultural Bank Finance Department, Saleh Mohamed Saleh, says rampant inflation has made it near-impossible to fix loan schemes for farmers. “If we lend a farmer an amount to buy a tractor and agree he will pay back the loan after five years, the same amount will not even buy a tractor wheel anymore,” Saleh said in an interview on Blue Nile TV.

Wheat production looks just as bleak in the once fertile Al-Jazeera region in central Sudan. “If the situation continues in this way, there will be no cultivation anymore in Al Jazeera,” says Ahmed Babiker, Secretary-General of the Al-Jazeera State Farmers Association. “All farmers will migrate to Khartoum to earn a poor living by doing odd jobs and marginal businesses.”

Faced with poor pricing options from the government, farmers are either giving up on farming or keeping their harvests to themselves.

Vast government warehouses are near empty of wheat in Dongola, the capital of Northern Sate. Between March – April, the wheat harvest in Northern State extended to an area of 130,000 feddans (1.03 acres), producing hundreds of thousands of tons of wheat, local farmers told Ayin. “No one will plant wheat again next season because of the Sudanese government’s actions,” says farmer Ali Mohamed Ali Gedo, claiming any future planting is a “guaranteed loss”.

The former commissioner of the Investment Commission in Northern State, Bushra al-Tayeb, told Ayin that there is no comparison between the agricultural preparation this year and that of last year due to the “government apathy” towards agriculture. Al-Tayeb says the government’s decision to increase electricity costs for agricultural projects six-fold is the main reason farming in Northern State has significantly reduced.

Unable or unwilling to sell their harvests to the government, some farmers are resorting to selling their wheat crops to traders who export it to Egypt, according to Tariq Ahmed Al-Hajj, head of the Al-Jazeera Farmers Association, where Egyptian merchants purchase wheat for around 60,000 Sudanese Pounds per sack.

In the restive Darfur region, it is not a matter of farmers being unwilling to harvest this year, insecurity simply makes it impossible to do so.

Too dangerous to till

The Darfur region was once the country’s breadbasket, providing around 70% of the country’s source of maize and millet and 85% of Sudan’s groundnut and sesame crops. Now, due to high insecurity, many farmers are displaced from their land by heavily armed pastoral militias and targeted if they attempt to return to farm their land.

In early June, seven farmers displaced by conflict and residing in Kalma and Al-Salaam camps in South Darfur State attempted to return to their home villages to farm near Ladoub town. Armed men attacked them, killing six and wounding the other, blocking them from accessing their land, local official Harun Omar Ali told Ayin.

The plight of these seven farmers is echoed across the region.

A survey conducted in North Darfur State by the state authorities and FAO revealed a near 200 million metric ton deficit in food production this year. The Director-General of the Ministry of Agriculture in North Darfur, Dr Inam Abdel Rahman, attributed the shortage to the ongoing armed conflicts as the main causal factor, with high prices and desertification as secondary contributors.

“We cannot reach our farms for several reasons, including the systematic violence against farmers by shepherds,” says farmer Issa Ali Adam, who used to farm near South Darfur’s capital city, Nyala. According to Issa Ali, insecurity, runaway fuel prices and general economic uncertainty has doubled the number of people in need of food within cities and displacement camps in South Darfur State. “Three farmers were beaten, killed and their agricultural machinery was looted last week (late May) by gunmen south of Nyala when they were planning the land for cultivation,” he added. “Despite filing complaints against the aggressors, the security forces responsible for protection did not arrest them. The perpetrators have an affiliation with the security forces.”

Individuals within the government are certainly trying to curb food shortages. According to the Director-General of the South Darfur State Ministry of Agriculture, Hammad Musa Matar, the state has planted 15 million feddans of maize and millet this year –three times what was planted last season. The government official, however, fears the conflict between pastoralists and farmers may affect the project. In March, the state government also held a conference with civil leaders to mitigate violence during the agricultural season by developing livestock migration paths and water resources as well as a law to regulate agriculture and grazing.

But in terms of government efforts to provide physical security for farmers, Darfur residents say, authorities continue to support the heavily armed pastoral groups that routinely loot and displace the farming community.

Take, for example, the recent fighting in the Kulbus area of West Darfur State. From 6 – 11 June, attacks by armed militias in Kulbus and neighbouring villages killed at least 125 people and displaced an estimated 50,000 others, the UN reported. A local leader in the area, Abkar al-Touma, told Ayin that the authorities ignored the plight of civilians from five villages around Kulbus as armed militias burnt their villages to the ground and looted hundreds of heads of cattle.

With most of Darfur’s original farmers now conflict-displaced, residents say, there is simply no one able to safely work in agriculture, despite the country’s severe needs.

The levels of displacement, especially in Darfur, continue. In May, the UN announced that the number of displaced people in Sudan rose to 3.1 million after 75,000 people were conflict-displaced in Darfur this year alone.

Forced to import

With local production severely curtailed by farmers unwilling or unable to farm, the government has relied on costly imports. But accessing foreign markets is also proving to be a challenge.

The war in Ukraine has disrupted grain shipments from Russia and Ukraine, which account for over 80% of Sudan’s wheat imports. The Sudanese Professionals Association, a group that spearheaded the December 2018 revolution that toppled former president Omar al-Bashir in April 2019, has severely criticized the current coup leaders for spending millions on wheat imports. According to a statement by the association, the authorities imported over 900,000 tons of wheat from January – March this year, costing the penurious government US$ 366 million -a huge sum in comparison to the same time last year whereby the civilian-led government spent US$ 86 million and imported 288,000 tons of wheat.

High prices, bread revolution

With limited access to wheat and the highest rate of inflation in Africa, Musa Ali fears fewer and fewer customers will be able to purchase his bakery’s bread. The lack of bread will induce more hunger, Ali says, as well as trigger further political unrest. “The revolution started with protests over bread prices,” Ali told Ayin. “People shouldn’t forget how important bread is.”