Darfur displacement continues to rise

25 August 2021

“Why is it when they claim there is peace, we still hear gunfire?” asks Fatima Abdel Karim, a young woman displaced by conflict residing in Autash, an Internally Displaced Persons [IDP] camp in South Darfur State. “You still see new displaced people coming into the camp […] so where is this peace they talk about? If you asked me 1,000 times, I cannot say we have peace [in Darfur].”

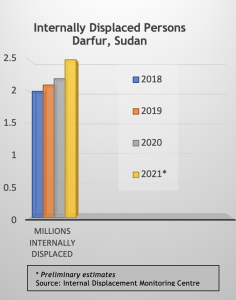

Unfortunately, the numbers displaced by conflict in Darfur since the transitional government came into power reflect Fatima’s sentiments. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) in Geneva, Switzerland, there were 79,000 newly displaced from conflict and violence in Sudan last year. In 2021, preliminary findings suggest there are already 333,8000 new internal displacements linked to conflict – with 97% of these cases coming from Darfur. “The number of new internal displacements in Sudan has increased at an alarming rate in recent months,” says Manuela Kurkaa, a Monitoring Expert at the Centre. “We have recorded nearly four times as many conflict displacements in 2021 as we did in all of 2020.”

“The number of new internal displacements in Sudan has increased at an alarming rate in recent months. We have recorded nearly four times as many conflict displacements in 2021 as we did in all of 2020.”

— Manuela Kurkaa, Monitoring Expert, Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre

One of the worst conflict-related displacements took place at the beginning of the year. A January surge in inter-communal attacks in West, South, and North Darfur states forced more people to flee their homes in three days than in the whole of 2020 in Sudan, IDMC reported.

These attacks have not abated as the year progressed. Earlier this month, armed groups attacked the displaced who had returned to their farms for the planting season in the Kolgi and Qallab areas, killing three people and wounding 10 others. In response, the North Darfur State authorities formed a joint security force to protect the farmers during the agricultural season. The joint force comprised of government security forces and former rebels now aligned to the government under the Juba Peace Agreement. After three days of protecting the agricultural area, an armed group ambushed the security forces, killing six and wounding 21 of them, according to news reports.

These attacks have not abated as the year progressed. Earlier this month, armed groups attacked the displaced who had returned to their farms for the planting season in the Kolgi and Qallab areas, killing three people and wounding 10 others. In response, the North Darfur State authorities formed a joint security force to protect the farmers during the agricultural season. The joint force comprised of government security forces and former rebels now aligned to the government under the Juba Peace Agreement. After three days of protecting the agricultural area, an armed group ambushed the security forces, killing six and wounding 21 of them, according to news reports.

As a result of these events, around 5,300 families were displaced and fled to Zamzam, Shaqra, and Tawila IDP camps, Sudan’s Humanitarian Aid Commission (HAC) reported. “North Darfur witnessed the displacement of approximately 38 villages in the span of three days,” Adam Mahmoud Abdullah, a resident of Zamzam IDP camp told Ayin. “This is the highest displacement rate since the signing of the Juba Peace Agreement.”

Juba Peace Agreement

There were high hopes that the peace agreement between 11 rebel groups and the government signed in Juba last October would engender greater peace and security for Darfur’s displaced population. The agreement itself stipulates that the signatories would establish an IDP and Refugee Commission within 60 days of signature to oversee, administer and facilitate the voluntary return and resettlement of those displaced by conflict in Darfur and elsewhere. “The Parties shall pay special attention to protecting internally displaced and refugee women, children, and all other vulnerable groups from all forms of harassment, exploitation, and sexual or gender-based violence,” the agreement also states.

In terms of reducing conflict between the government and rebel forces, the agreement could be viewed as a success – but it has also left a vacuum for other forms of insecurity.

Intercommunal violence

Since late 2020, the region is seeing more people displaced by criminal violence and inter-communal fighting over land, Kurkaa told Ayin. “Most new displacements have taken place in Darfur and have been driven by intercommunal violence and disputes over land and resources,” she said. “Armed groups are further exploiting inter-communal tensions and power vacuums in some areas for political gain.”

In the past 10 years, Arab herders in Darfur and nomads from countries west of Sudan were invited by the former government of Omar al-Bashir, ousted in April last year, to inhabit the areas where Darfuri farmers used to live before being displaced by conflict. For years, government-aligned militias protected and, in some cases, continue to protect these new “settlers”.

Whenever the original farmers try to return to these lands from the IDP camps, conflict erupts between them and the new occupants. The new settlers, heavily armed by the previous regime and, in some cases, still protected by government forces, retaliate with violence.

The African Union and United Nations hybrid peacekeeping force, UNAMID, provided at least a modicum of protection for some of these farmers, Kalma IDP camp resident Osman Adam told Ayin. But once UNAMID withdrew all personnel in June this year without its agreed national replacement, a wider security vacuum developed.

“After UNAMID left, attacks increased,” says Ehssan Mohamed, Women Director for IDP camps in South Darfur State. “The Juba Peace agreement has failed, failed, failed –-up to now nothing has happened. Criminals are still happily looting. Secondly, no criminals have been taken to court, and thirdly, there are more weapons circulating around than before. Previously when we were in the IDP camps, there was nothing called a gun – but now even young kids are carrying them.”

Dr. Suleiman Sandel, Political Secretary of the Justice and Equality Movement and Vice-Chairman of the Security Arrangements Committee is acutely aware of the problem. A former rebel leader under the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), Sandal says a security arrangement must be implemented to assist voluntary returns and prepare for the agricultural season. During an address at a training course on peacebuilding and civilian protection for armed movements, Sandel said the recent events in the Kolgi region of North Darfur highlighted the pressing need to implement security arrangements and form a joint force in Darfur. “In the security arrangement (from the Juba Peace Agreement) we agreed to construct a force to protect Darfur – 6,000 from Sudan’s army and 6,000 from rebel groups, but we have a lot of challenges,” Sandel told Ayin. “First of all, we just came out from a war and our and troops are everywhere – another challenge is there are a lot of weapons in the civilians’ hands and also we need funds [to set up the peace force] –it’s not easy.”

Distrust

But even if a national peacekeeping force is set up and fully functional, there is little chance Darfur residents will accept and trust such a force –especially since the Rapid Support Forces will be part of these deployments. Few of those displaced in Darfur trust the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) given their infamous track record of brutalizing civilians. The RSF were re-branded from their former nomenclature as “Janjaweed” –an infamous, armed militia set up by Bashir to counter Darfur rebel movements.

According to Mohamed Osman, a researcher with Human Rights Watch (HRW), Sudan still has a long way to go in terms of security sector reforms. “Deploying forces with poor rights records, which are neither trained nor equipped to conduct rule of law operations, creates an environment ripe for abuse, as we have already seen,” Osman said in a statement.

Many of those currently residing in Darfur’s displacement camps say they see little difference between the ‘Janjaweed’ of the past and the RSF now assigned as part of a joint peace force. “How can a government-supported force be within the camp?” questions Ehssan Mohammed. “They bring the Rapid Support Forces to protect us, but we do not trust them because they are the ones who displaced us in the first place. They displaced us to this camp, and we have remained in this camp up until today – even if we stay in this camp forever and this camp will be our gravesite, we cannot accept [these] troops.”

Similarly, pastoralist Arabic tribes are also wary of the joint peace forces –suspecting the former rebel groups will remain impartial towards them. The Coordination of Arab Tribes said in a statement that forces affiliated with the former rebel Sudan Liberation Army and those formerly linked to the Darfur regional governor, Minni Minawi, carried out an attack this month on Arabic civilians in Damra Koulaki, killing several people in retaliation over a land dispute.

Displaced yesterday, displaced today

With land disputes taking place between armed communities across Darfur in this security vacuum, the levels of displacement in the region appear set to increase. The victims of this displacement will largely remain the same as before: civilian farmers.

According to Kurkaa, many of those who suffered displacement during Darfur’s war are the same facing displacement today. “Internal displacement in Sudan is largely protracted, as 57% of the IDPs who live in the country were displaced between 2003 and 2010 and have yet to reach durable solutions or an end to their displacement.” Over half of IDPs in Sudan face food insecurity, Kurkaa added.

Severe food shortages will likely continue if not increase since many of those displaced in Darfur are unable to farm due to the ongoing insecurity.

“The state is still witnessing a wave of displacement of citizens to El Fasher — conflicts between farmers and armed militias are still ongoing,” says Rania Mater, a civil rights activist based in North Darfur State’s capital, El Fasher. Matar says many displaced have lost all their farming equipment amidst this violence, making it even harder to cultivate even if the violence stops.