Hospitals in the crosshairs – The targeting of medical staff and patients in El Fasher

12 February 2026

For months, El Fasher was cut off from the world. No safe roads, no reliable communications, no functioning supply chains. Inside the besieged city, hospitals became islands of desperation. Doctors worked without anaesthesia, without electricity, and often without hope. Yet they kept going.

Dr Ezzeldin Aswo, a surgeon, was one of them; during the siege, medical teams performed more than 12,000 surgical operations. They carried out many of those procedures at night, under bombardment, using only mobile phone flashlights to illuminate open wounds. Operating rooms were reduced to bare survival spaces, where the priority was no longer recovery but simply keeping patients alive long enough to see another sunrise.

After enduring 16 months of fighting between the army and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), the latter overtook El Fasher, the capital city of North Darfur State, in October last year.

As the siege tightened, even basic technologies collapsed, Dr Aswo told Ayin. Internet access was impossible. Starlink devices existed, but they were useless without generators or solar power – both impossible to operate under constant shelling and targeted attacks. Communication blackouts were total. No one knew what decisions were being made or whether the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and allied Joint Forces (JF) intended to hold the city or abandon it.

On the day El Fasher fell, Dr Aswo and those with him tried repeatedly to leave. They attempted to escape through the southwest and northwest routes, the same directions where they saw soldiers from SAF and JF withdrawing. At that time, they had no idea that an official withdrawal order had already been issued. With communications jammed, civilians and soldiers alike relied only on what they could see with their eyes: people leaving and danger closing in.

Fleeing El Fasher

“The shelling that morning was relentless,” Dr Aswo said. “In the streets, artillery fire fell without warning, tearing through fleeing civilians. Bodies were torn apart in full view of those running for their lives.” Movement became almost impossible. Still, they tried. Their first attempt took them toward the Airport neighbourhood in the southwest. There, they encountered the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) units already positioned in the area.

The fighters shouted orders and racist insults, demanding surrender. Panic took over. Dr Aswo and the group of medical staff ran. RSF fighters chased them on motorbikes, firing as they fled. One man, Al-Hadi, was shot in the neck. The bullet severed a main artery. His son screamed for help.

Dr Aswo stopped and examined the wound. There was nothing he could do. Under fire, without equipment, the injury was fatal. He told his son, “We can’t save him; we have to keep running.” Staying meant death for everyone.

They retreated into the city, toward the Faculty of Engineering at the University of El Fasher, an area usually controlled by the SAF, and remained there until evening. As darkness fell, streams of civilians and soldiers once again attempted to flee. This time, they joined them, walking on foot through the night.

Hours passed. Thirst became unbearable. Dr Aswo collapsed from dehydration and told his companion he could not continue. They stopped where they were and slept on the ground. They woke up at dawn to a terrifying realisation: they were in an RSF-controlled village on the outskirts of El Fasher.

When they asked for directions to Tawila, RSF fighters confiscated their phones and money, then beat them. They were accused of being part of the army. Interrogations focused obsessively on tribal identity. Those who did not belong to tribes perceived as aligned with the RSF were insulted with racist language and subjected to harsher violence.

After being stripped of everything they owned, they were forced to sit under a tree for hours. Dr Aswo’s colleague had hidden US$5,000 in his underwear. When the money was discovered, the beatings escalated until sunset. Only then were they allowed to leave, given vague directions toward Tawila.

They walked all night again. Near dawn, as they approached the town, his companion stopped to remove thorns embedded deeply in his foot. At that moment, an RSF four-wheel-drive vehicle arrived. Fighters fired into the air, shouted racial slurs, and forced them into the vehicle.

They were taken to an abandoned village near Tawila. There, dozens of detainees were already being held. The group were beaten collectively until sunset. By Dr Aswo’s estimation, there were 38 detainees.

Conditions were brutal. All detainees shared only 4.5 litres of water per day. A small teacup of water was considered a stroke of luck. Food consisted of one kilogram of rice in the morning and another in the evening, which detainees cooked themselves and divided among the group.

Each day, four or five detainees were taken to a nearby location with Starlink internet. There, they were forced to call their families and demand ransom. Payments were set arbitrarily, often based on tribal identity. Dr Aswo hid his profession, fearing that revealing he was a surgeon would lead to either forced labour treating RSF fighters or accusations of having treated army personnel.

Detention and disease

Another medical worker, based at the Saudi Hospital in El Fasher, witnessed the city’s collapse from a different angle. Salah* had remained in El Fasher throughout the siege, watching medical supplies vanish and prices spiral. By the final weeks, one kilogram of rice cost as much as US$ 200. Medicines were almost entirely unavailable.

Worst of all was the constant shelling of the hospitals. “Even the army’s own headquarters was not hit as heavily as the Saudi Hospital in El Fasher,” Salah told Ayin. “Nowhere faced more shelling, gunfire, and drone strikes than that hospital.” Even before the RSF took control of the city, Saudi Hospital was under bombardment. “The surgical complex where I worked was struck three times in one month by drones and C-5 rocket launchers. We had to relocate the hospital multiple times because of the shelling.”

When the situation became unbearable, Salah decided to flee early in the morning the day the RSF took over El Fasher. He never made it out.

Around 10 am, in a familiar area northwest of the city known as Qarni, Salah was arrested. Thousands of people were gathered there – men, women, and children – trapped and surrounded. Salah estimated the number to be between 6,000 and 7,000.

Hours passed under armed guard. At around 2pm, women were separated from men and taken deeper into Qarni. The remaining group was ordered to move under heavy escort, only to be returned to El Fasher later that day. Throughout this ordeal, the medical worker concealed his profession, knowing that disclosure could mean forced service or death.

Detention conditions deteriorated rapidly. Children held nearby began showing symptoms of acute watery diarrhoea. The outbreak spread quickly. Eventually, it became known that Salah had medical training. He began treating the children with whatever minimal resources were available.

He remained detained for at least thirty days. As the disease spread, torture decreased – not out of mercy, but out of fear. The guard became reluctant to enter the detention area, worried about infection. “Illness, briefly, became a shield,” Salah said.

Some detainees managed to escape. Others did not survive. Eventually, Salah managed to escape and lived to recount his experiences.

What haunted him most was what happened to his colleagues. On the day El Fasher fell, attackers killed some of the medical staff present at the Saudi Hospital. The hospital bombing also claimed the lives of patients and their companions. A place meant for healing became a mass grave.

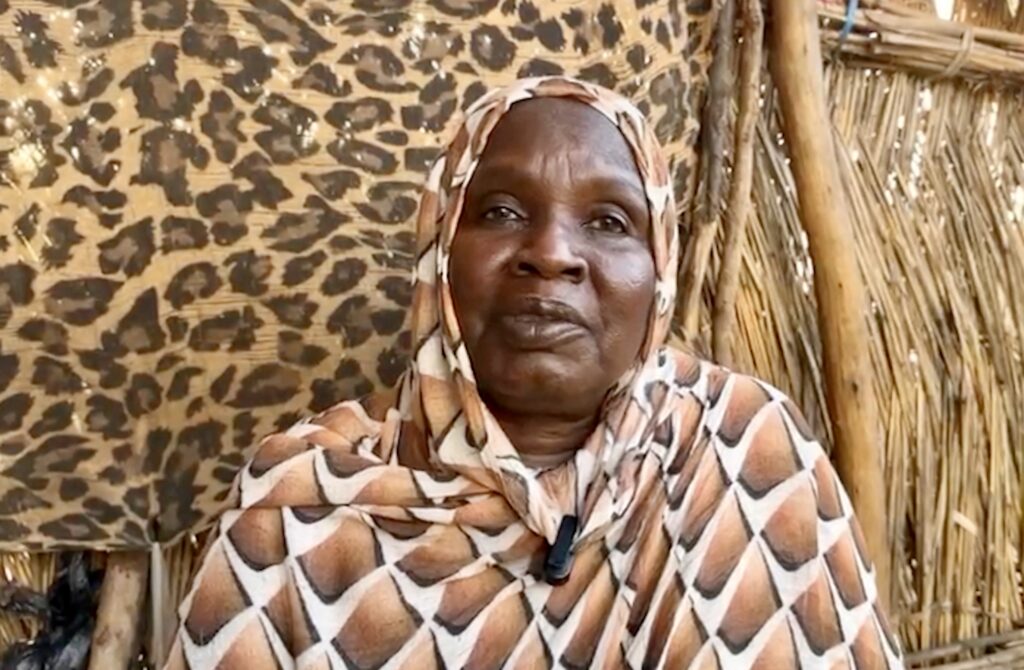

Fatima Mohamed was a patient at Saudi Hospital when the RSF attacked. “People were being torn apart, heads severed, and limbs blown off while the rest of us hid under hospital beds,” she said. Fatima saw eight members of her family die – including children.

After the RSF takeover, the health system collapsed entirely. Health facilities were looted or destroyed. The dearth of healthcare not only affected El Fasher but the entire area. Fatima was compelled to travel all the way to Adré, a refugee camp in eastern Chad, to find any treatment for wounded family members. “We brought the wounded to Tawila, but there were no doctors. We had no money for medication. We moved to Golo—still no help. After two nights, we moved again to Nertiti. From there, we finally crossed into Adré, in eastern Chad,” she said.

Al-Toma Mohammed faced similar challenges as Fatima and found herself in Adré fleeing the conflict and searching for medical treatment. “We carried children in our arms—metal rods still inside their broken legs, their wounded hands wrapped and tied—and we fled.”

A silent tragedy

Months later, survivors’ testimonies from the siege of El Fasher last October are gradually emerging. The total communication blackout ensured both local and international communities remained ignorant of the scale of destruction.

“I did not know what happened to my brother for weeks,” said Samira*, a displaced young mother who managed to flee El Fasher and sought shelter in the sprawling displacement camp in Tawila, North Darfur State. “When the fighting started, we got separated and lost contact completely.” Samira is one of the fortunate ones. Eventually, by sheer chance, they found each other in Tawila. But for many others, the fate of their relatives and loved ones remains unknown to date.

Communication blackouts played a deadly role. With no information, civilians fled blindly into danger. Without power, lifesaving technologies became useless. Without accountability, violence escalated unchecked. El Fasher remains in what the UN describes as a “near total blackout” today.

Although these are only estimates, a recent humanitarian briefing at the United Nations Security Council indicates that around 100,000 people are currently residing in El Fasher, while approximately 1.2 million people have either been displaced or killed. Yale University’s Human Rights Lab (HRL) claims that the RSF have been burying and burning remains to conceal mass killings in El Fasher. Yale’s December report said the RSF “engaged in a systematic multi-week campaign to destroy evidence of its widespread mass killings,” and “this pattern of body disposal and destruction is ongoing.”

Other reports claim the RSF is converting public institutions, including the Children’s Hospital in eastern El Fasher, into makeshift detention centers where potentially thousands are being held in often inhumane conditions.

Currently there is little reliable information other than the testimonies of those who fled the area.

What remains now are the voices of those who survived. Their testimonies stand as records of what happened when a city was abandoned and of what it cost to stay alive when survival itself became a crime.