Another pandemic: Rising domestic violence under quarantine in Sudan

The pandemic has caused all countries to direct citizens to stay home to protect themselves and others, yet for domestic violence victims; home is also a dangerous place to be. Domestic violence numbers had amplified significantly according to the UN, describing it as a “shadow pandemic”.

Their figures showed that 243 million females – globally- aged 15-49 have experienced sexual and/or physical violence committed by an intimate partner during the outbreak of covid-19 and the lockdown.

Sudan, unfortunately, is no exception to this heightened trend in domestic violence. According to the head of the gender-based violence Unit in South Darfur State, Fatima Abaker, several women in the state have died from domestic violence cases during the Covid-19 lockdown period. “With the current curfew in Sudan, a rise in domestic violence was expected, but it wasn’t expected to reach murder,” Abaker said.

The COVID-19-induced movement restrictions and economic hardships have created challenging psychological circumstances for Sudanese citizens, says Psychologist Dr Ali Baldu. Facing an inability to control their situation amidst stress and anxiety over daily fiscal concerns, families are contending with pent up aggression that leads to verbal and physical abuse, Dr Baldu told Ayin. Even children are not safe from it. “There must be psychological support channels and awareness-raising programs for us all to survive this period”, he added.

Living in Dangerous Situations

Options for Sudanese women facing domestic abuse are few and far between. There is little protective legislation in place for cases of domestic violence and many female survivors of domestic abuse face obstacles accessing the police fearing social stigma. Others reach out to family members for support.

Rehan* is a mother of four from Omdurman and a survivor of domestic abuse from her husband. On 5 February, Rehan’s enraged spouse attacked her with a sword as she lay next to their newborn and other children. Rehan was left with severe injuries to her neck, hands and abdominal area –requiring intensive medical and psychological care. The parent’s eight-year-old son came to Rehan’s rescue, only to face his father’s wraith. Eventually, the father ran into the street towards their relative’s nearby home carrying his 4-year old daughter, stains of his wife’s blood on his clothes. People coming from morning prayers met them and called the police; “I killed my wife”, he told them. Rehan’s family rushed her to the hospital to stat the long journey of recovery.

Suffering from depression, major wounds and other health complications related to the head injury, Rehan is slowly recovering from her ordeal. According to the local press, her perpetrator said later that if he knew she survived, he would have gone back to finish her. The husband remains in jail after being released temporarily in April and faces charges of attempted murder according to a SIHA (Strategic Initiative for Women in the Horn of Africa), women’s advocacy and support organisation.

Rehan’s Aunt told Ayin that he poses a great danger to her and her children -who are still in shock- if he is to be released. Even from prison, the Aunt said, the husband managed to contact a relative to Rehan and threatened them. An authoritative family figure, Rehan’s husband kept her away from any contacts with family and friends since their marriage commenced. Rehan’s Aunt is determined she will pursue justice for her niece.

While Rehan’s case is extreme, there are numerous reports of egregious domestic violence cases in Sudan – with many reported in the capital, Khartoum.

The Women and Child Protection Unit in the Ministry of Social Welfare documented 40 cases of violence – most of them within the state of Khartoum. “All those cases were offered psychological support, but it’s still not enough”, says Dr Sulima Ishag, the head of the Unit.

Dr Ishag says that legal support should be provided but few courts and public-attorney offices are open during this corona period, leaving many survivors of domestic violence without access to the legal recourse.

“Many women had filed cases already in police stations against their abusers, however, they [the perpetrators] get out of the lockup with a simple guarantee, this places these women in danger again once the abuser returns to the homestead,” she says.

“We make sure to direct the victims to child and family protection services as they are more specialized than regular police”, she said adding that last April the Unit launched a hot-line service to receive the complainants of domestic violence taking place across the country.

In the town of “Bulbul Dalal Al-Angara” in South Darfur state, Mariam Abass* was killed by her husband during the quarantine period. “The murder took place when the married couple had a fight and she went to the house of a female-relative in a nearby town,” according to Mariam’s cousin Aldoma Adam. The husband followed Mariam, demanding that she returned home, Aldoma Adam added and killed her with a sharp object when she refused. The husband surrendered himself to the police. “To beat your wife to death is unheard of here, something we are not familiar with in our town”, Adam said.

Legal and Customary framework

While the cases of Mariam and Rehan took a firm legal course of action –they are the exception to the rule. The dearth of legal protection in domestic violence cases has resulted in few domestic violence victims seeking a legal solution. Dr Ishag’s unit is currently working to resolve this by drafting new articles to protect domestic violence survivors, she said.

Even while legal reforms are taking place, most survivors of domestic violence seek psychological aid over any legal action, Dr Ishag told Ayin. “Due to social stigmas attached to these cases, they refuse legal support,” Ishag explains. Traditional norms –where upholding the family’s name is considered sacrosanct to all other considerations—prevents many women from coming forward. “We have offered legal support to 40 women and also considered a safe house for them –but these ideas proved useless due to their traditional family structures.”

Developing more legal direction is supported by civil NGOs in Sudan, including SIHA, which filed a memo to the general public-attorney several weeks ago to combat gender-based violence in Sudan. “Stopping laws that discriminate against women and drafting new laws that ensure women’s civil rights is essential,” says Hala Al Karib the head of SIHA. Al Karib says they are pushing for specialized public attorney offices that focus on gender-based violence and state-supported safe houses so that domestic violence survivors can pursue their legal rights in a safe environment.

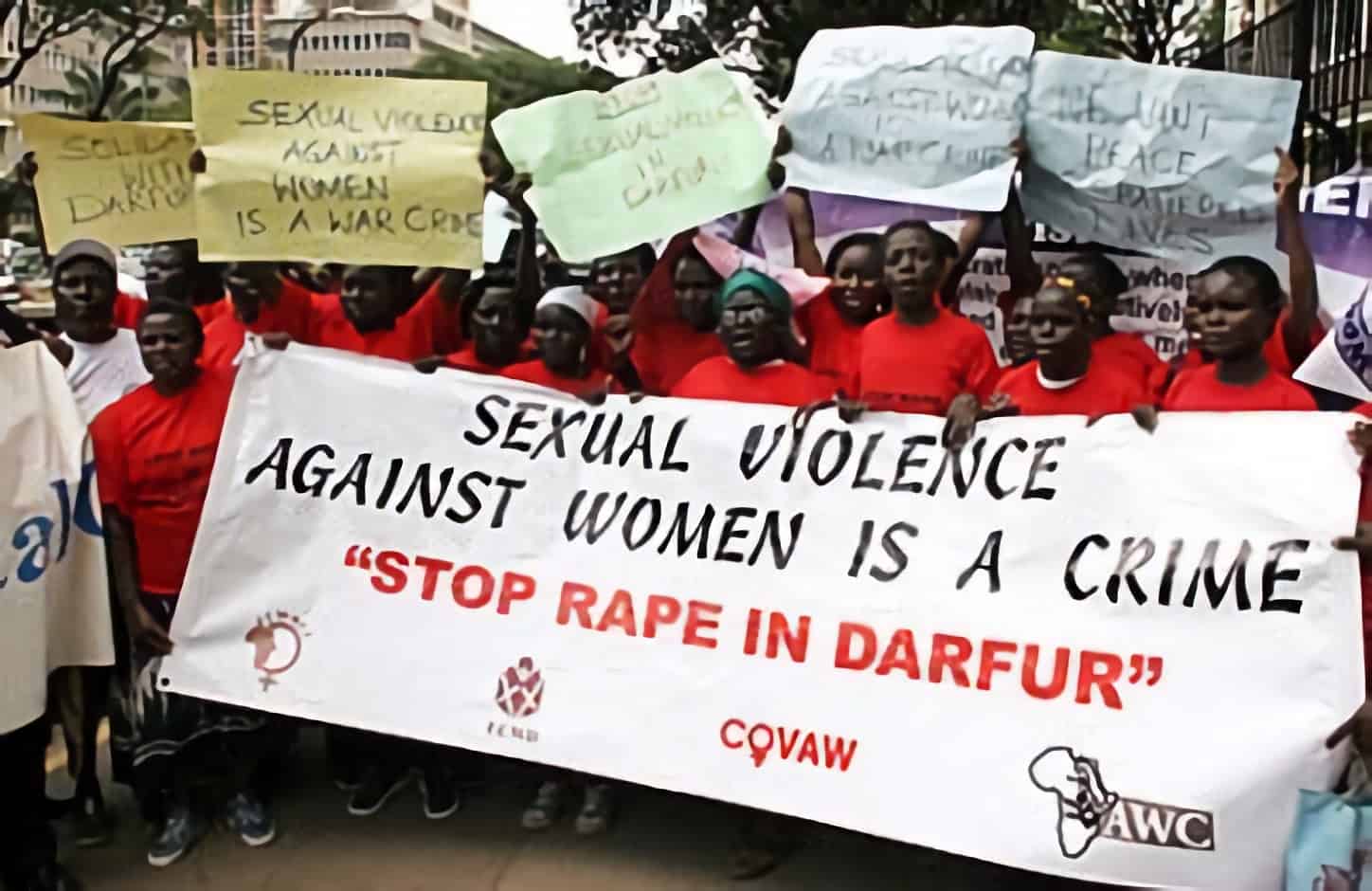

Darfur, violence without borders

South Darfur’s Head of Gender-based Violence Control Unit, Fatima Abakar, told Ayin they held an awareness-raising campaign at the beginning of the quarantine period, working in partnership with civil organisations. According to her, they launched several campaigns to limit the gender-based violence under the quarantine, but face an uphill battle with more cases reported in the quarantine period.

“During our work, we recorded an increase in the number of murders of women by their spouses, including five cases in Al Salam municipality in addition to others in Tulos County and three in Nyala city, in addition to one murder in a refugees’ camp. We checked and confirmed three of those cases. The families of victims are trying to cover-up those incidents”.

Attempts to bury these crimes go back to the nature of Darfur’s community and general traditions in the area, Fatima Abaker says, with most cases being settled outside of courtrooms. “Usually the settlement comes in the form of financial compensation called ‘dia’; which is highly unjust to the victims,” she added.

The unit’s primary role in these cases – according to her – is providing comfort; “We cannot interfere legally, but we try to intensify awareness-raising efforts to limit the violence, and manage hotlines to provide psychological and legal aid to decrease the impact of assaults on the victims.”Abakar says they have one domestic violence survivor case that is seeking legal action, a move she supports since it could act as a deterrent to future cases and works better than relying on Darfur social customs that often discriminate against women.

From North Darfur State, the Chairperson of the Family and Women Affairs Unit in the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, Nidal Senin also told Ayin that the cases of gender-based violence had increased with the current movement restrictions especially in the municipal districts and refugee camps.

Nidal Senin points out that the Unit drafted a plan to work with victims under the COVID-19 curfew, providing them legal counsel to seek legal justice. But Nidal Senin admits there is still a lot of work to be done.

For a start, given the social pressures to maintain a benign family image, very few people report domestic violence cases in Sudan. There are no statistics to gauge the level of the problem and Senin and others admit their monitoring only scratches the surface in terms of cases.

Without quantitative research and legal measures to help quell gender-based violence, such cases will, unfortunately, continue –with or without the COVID-19 quarantine.

* Names changed for security reasons