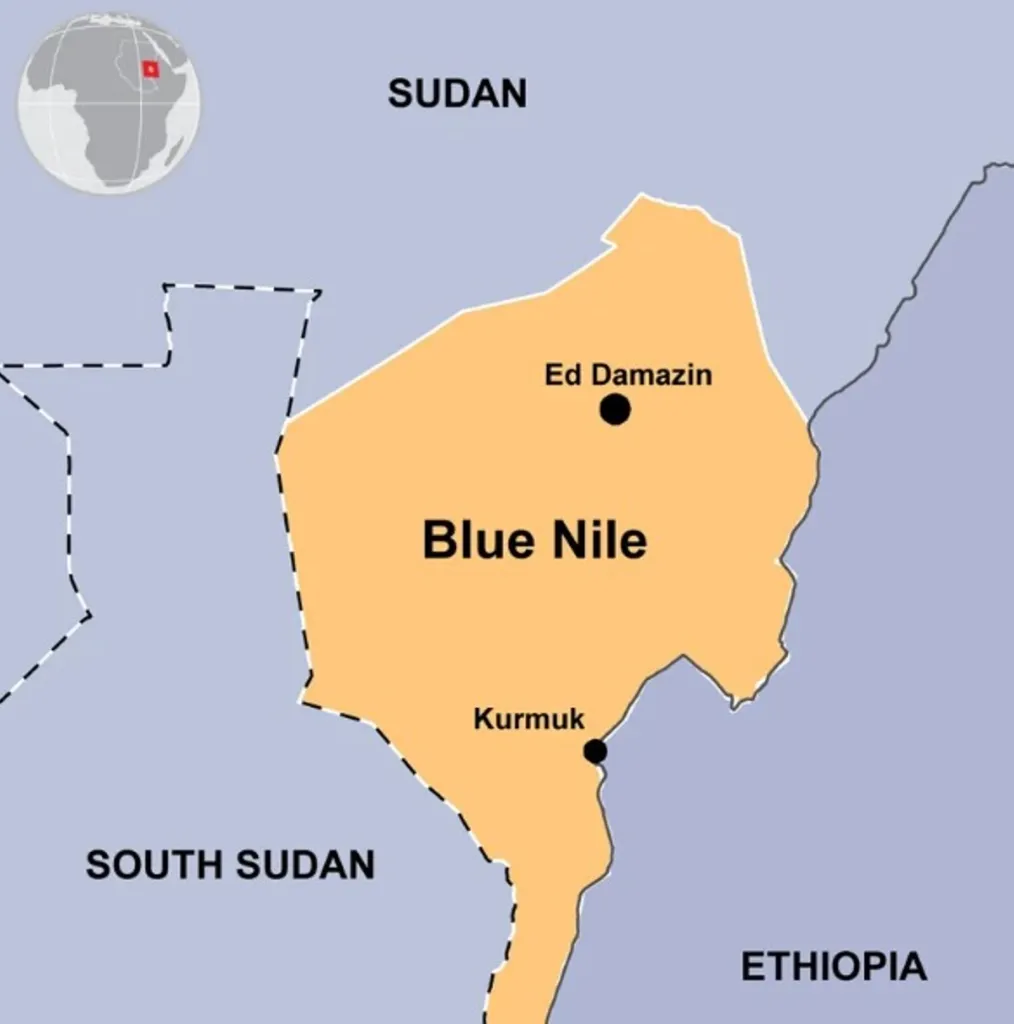

Violence in Blue Nile – an avoidable crisis

20 July 2022

In some of the highest levels of violence Blue Nile State has experienced in a decade, the Federal Health Ministry now estimate 105 deaths linked to the inter-communal violence that took place in several locations across the state. Protests led by the Hausa ethnic community have taken place across the country since the deadly violence that occurred in the southeastern state from 14 – 17 July.

On 14 July, armed clashes between members of the Hausa, Berti and Funj tribes started in multiple areas of Blue Nile state, including Quaisan town, the capital Damazin, and Roseires, the state’s largest city bordering Ethiopia. To quell the violence, State Governor Ahmed al-Omda issued a state of emergency on Saturday, prohibiting public gatherings and imposing a curfew from 6 pm – 6 am in Damazin and Roseires cities –with all roads leading to Damazin closed by security forces.

But clashes continued throughout the evening on Saturday despite the directive, according to a statement by the Central Committee of Doctors. One merchant based in Roseires, Muhammad Hamad, told Ayin he saw a massive fire spread across the main market in Roseires, destroying all the shops and stalls while the streets were in chaos amidst a complete absence of security forces.

By Monday, calm returned to the state, according to the Sudan army spokesman, Nabil Abdullah, and the attorney general has been assigned to set up a committee to investigate the incident to identify the perpetrators behind the violence. The military authorities who ousted the civilian-military-led government in October last year are facing increasing pressure from protestors and opposition groups who accuse authorities of mishandling the crisis.

Mass displacement, injuries

Besides a high death toll, an estimated 14,000 people are now displaced due to the conflict with the majority being women and children, according to the head of the International Committee of the Red Cross in Damazin, Al-Tayeb Ahmed Zayed. The displaced are in three schools belonging to the armed forces near Souk al-Kawda and Block 56 in the al-Qassam neighbourhood, south of the capital, he told Ayin. Zayed believes the total number of displaced is, however, likely higher since many of the displaced have fled to Sennar State. Sennar State Governor, Al-Alam al-Nour, announced in a meeting today the formation of a state committee to provide support for the displaced.

Hospitals in Damazin and Roseires are overflowing with patients alongside a dearth of medical resources to treat the wounded, according to a statement by the Central Doctor’s Committee. Heba al-Tarifi, a member of the Damazin Resistance Committee, a neighbourhood movement that organise the protests against the military coup, told Ayin that the Damazin Teaching Hospital is overwhelmed with wounded patients amidst a lack of basic medical supplies such as gauze, cotton and spirit. By Saturday, the hospital was contending with 144 injured patients, 80 of them suffering from bullet wounds.

“The health situation in Damazin Teaching Hospital is dire,” said state health minister, Gamal Nasser al-Sayed. “A number of corpses of the parties to the conflict have not yet been identified – the hospital’s mortuary is filled with bodies, resulting in foul odours permeating the facility, making it even more difficult for the hospital’s medical staff to carry out their work.”

In a press statement on Sunday, the Damazin Resistance Committees said that the authorities of the security services suspended the movement of ambulances transporting the injured to hospitals to receive health care under the pretext of the curfew.

With an uneasy calm now on the ground, humanitarian organisations have started to dispatch health and medical supplies for roughly 30,000 people, UN spokesperson Sofie Karlsson said, noting that humanitarian support is still limited. “These clashes are occurring at a time when humanitarian needs in Sudan are already at an all-time high,” Karlsson said. “Over 14 million people, currently require some form of life-saving assistance, [any] upticks in violence further exacerbate the humanitarian situation at a time when funding stands at only 20 per cent.”

Conflict roots

While medical personnel continue to frantically treat patients across the state with limited supplies, few state residents are surprised by the flurry of violence. Clashes spread last week in several towns after Hausa farmers clashed with Birta pastoralists in Adasi, an area near Qaisan.

But the root of the conflict stems much further back.

According to Blue Nile Governor al-Omda, the issue started in April when the Hausa tribe demanded their inclusion into the state’s administration, the official said in a television interview. Earlier in the year, the governor said, the Hausa community had chosen a leader to represent their affairs – a move that was rejected by the tribal administration in the region. The head of the Blue Nile’s tribal administration, El-Obaid Hamad Abu Shotal, openly questioned the Hausa’s demands for representation, claiming the area belongs to the “tribes of the Blue Nile” and that the Hausa were “guests” to the area.

While many Hausa have lived in Sudan for generations, other tribes in the state still perceive them as outsiders since the Hausa ethnicity is particularly prominent in West Africa. Some residents also claim the Hausa are favoured by the current military rulers since they supported the former National Congress Party under Omar al-Bashir in the past –-a claim many Hausa dispute.

These ethnic tensions have been palpable for quite some time, residents say and were duly ignored by local authorities. Blue Nile resident Ahmed Ibrahim holds the local and central authorities squarely responsible for the conflict, who, he says, ignored calls to try and defuse the crisis. “Everyone knew and appreciated the extent of the tribal tensions,” he said in an interview with Al-Araby Al-Jadeed. Authorities, including the governor, were completely absent at the beginning of the conflict, he added.

Fanning the flames

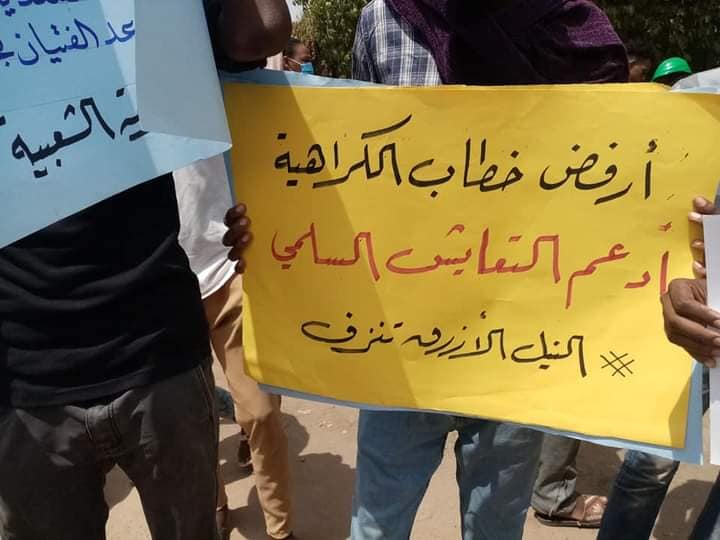

Many opposition groups have spoken out against the current military authorities for not only failing to provide security for civilians in the Blue Nile but also encouraging inter-communal violence in the first place. The Sudanese Professional Association, the pivotal group that organised the protests that helped topple former dictator Omar al-Bashir in April 2019, accused the military authorities of repeatedly failing in their role in protecting civilians and encouraging violence. “The coup authority is working to spread hate speech and racism through its leaders and deliberately igniting armed civil conflicts in order to preserve their authority,” the association said in a statement.

Former Sovereign Council leader Mohamed al-Faki Suleiman also accused the military leadership of fanning the flames of inter-tribal violence via social media saying the conflict in Blue Nile state was “a carefully planned matter,” and that these inter-ethnic conflicts always “start in Khartoum and not in the regions of Sudan.” The opposition party previously in power, the Forces for Freedom and Change, agreed on Tuesday to send their own independent delegation to the state to investigate events on the ground, independent of the fact-finding commission set up by the military authorities.

The Communist Party has accused the splinter faction of the rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) under Malik Agar of stirring up ethnic tensions within the state by supporting the Hausa community in return for Hausa recruitment to Agar’s SPLM-N forces. Agar has flatly denied the claim made by the communist party and plans to seek legal measures against them. The main SPLM-N wing under Abdelaziz al-Hilu has claimed in the past that Agar’s faction does not control any territory within the state and maintains few soldiers in its ranks.

If the accusations by civilians and opposition groups are true, the case of Blue Nile State and other parts of the country, particularly West Darfur, sets a dangerous precedent for Sudan’s future. In an interview with Al-Araby Al-Jadeed, retired Major-General Amin Mahjoub said the Blue Nile incident is the latest in a line of manufactured, tribal conflicts seen elsewhere in the country. “What happened in Blue Nile is an extension of political conflicts as political leaders have resorted to their tribes and clans to manage their battles,” Mahjoub said. “Sudan is at a crossroads that will restore tribal kingdoms to what they were about 200 years ago –-and this is what the world fears now about the future of Sudan.”

Solidary vs. tribalism

But political analyst Mohammed Ibrahim does not believe Sudan will fracture along tribal lines. The Khartoum-based analyst believes the revolution movement and access to information via social have encouraged social cohesion across the country. “The Sudanese people are more aware of political events in the country today than in the past,” he said, “unlike before, it is harder now for those in power to manipulate certain communities for political gain.”

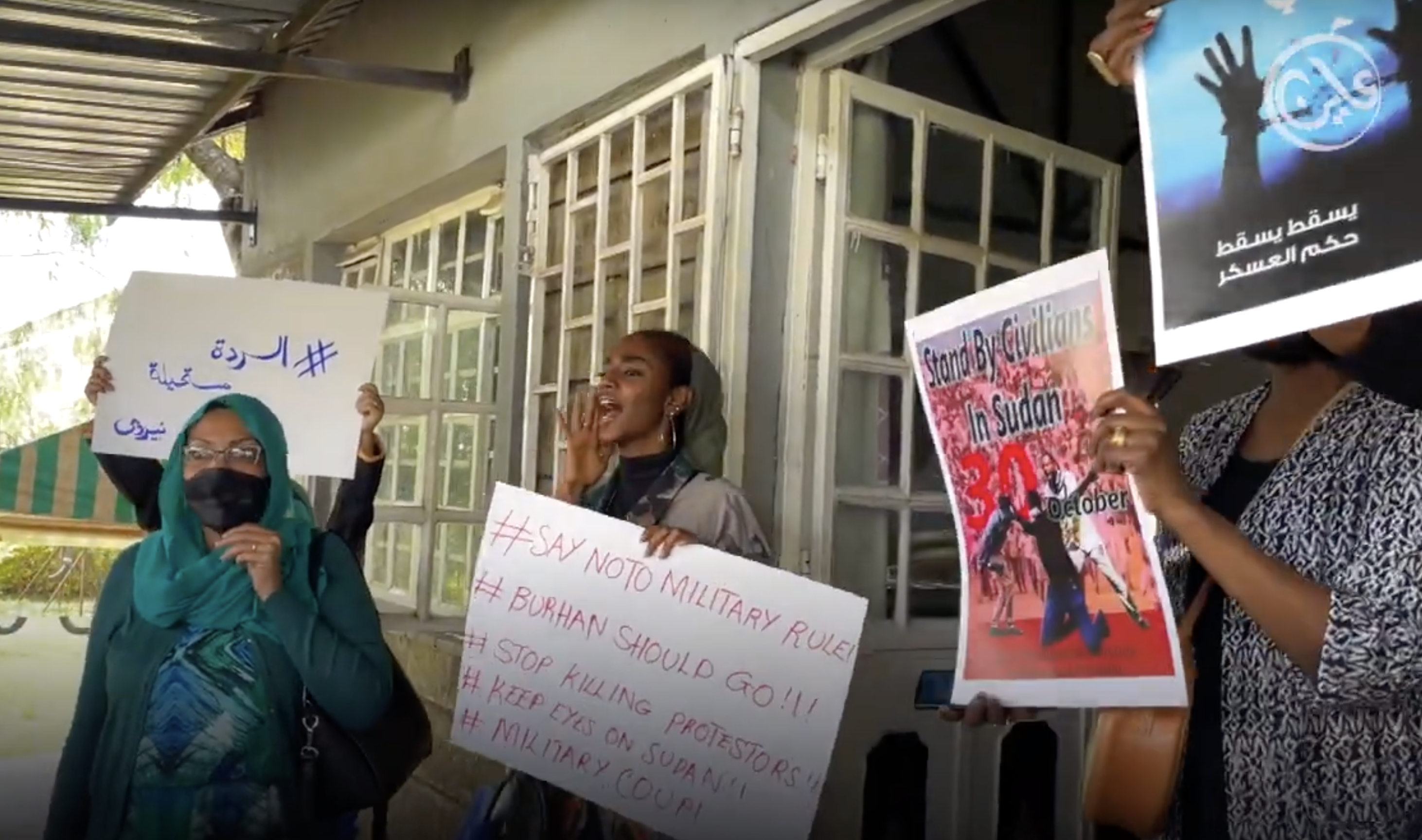

Since Sunday, protests have taken place across the country denouncing the violence in Blue Nile State and in solidarity with the state’s residents. Protestors marched in the capital last Sunday against the military leadership, holding it responsible for the outbreak of violence in Blue Nile State. Hundreds carried placards reading: “Blue Nile is Bleeding,” “Cancel the Juba Peace Agreement,” and “We support peaceful coexistence in the Blue Nile,” as they marched towards the presidential palace. Around 200 kilometres south of the capital, protesters in the city of Wad Medani donated blood at a local hospital to support those wounded in Blue Nile State, the wire agency Agence-France Presse reported.

The Hausa community also came out in large numbers on Tuesday across Sudan in support of their community in Blue Nile State. Some 4,000 people marched in the eastern border town Gedaref, for instance, chanting “Hausa are citizens too”. Similar protests took place in El-Obeid and Port Sudan. Authorities prevented public gatherings in Kassala, however, after demonstrators set fire to and vandalised government buildings and shops.