Rights denied: Sudanese women’s struggles continue after the revolution

2 April 2020

In the past week, human rights activists witnessed a severe set-back for Sudanese women with an online campaign calling for men to lash Sudanese women in public for “indecent” clothing such as wearing pants or going out without a headscarf. The campaign came as the Sudanese community was still under shock over the19 March murder of a schoolgirl named Samah El Hadi in El Salha, Omdurman. While the family claimed her death an accident, an autopsy report –originally ignored by police—revealed she was shot multiple times, allegedly by her father.

This was followed by reports of another victim, a 19-year-old woman in Omdurman, allegedly stabbed to death by her husband, and then buried without involving authorities. Around the same time, another schoolgirl was purportedly killed by her father in El-Fasher, North Darfur, simply for speaking to a man.

These incidents took place while the Head of Police in Khartoum State, Lt. General Eissa Ismael, remarked in a live interview that “no one is lashed for no reason,” and suggested the revival of the state Public Order Law to curb miscreant behaviour linked to the greater social freedoms found in the post-revolutionary period. The Police Chief called for the notorious law to be reinstated in a different fashion and declared that the murder of El Hadi bared no criminality, adding that “procedures taken by the police are legal and professional.”

The State Public Order Law was identified by women during the revolution as one of the key oppressive tools used by authorities to target often poorer Sudanese women, incurring mass profits through arbitrary fines and detentions. The state law was abolished in November 2019 under the new transitional government.

“We fought back long and hard for our rights to abolish the Public Order Law and are still pushing to remove other offensive and humiliating law articles. We will not have these laws brought back after all the sacrifices of the revolution,” says Ayat Hassan, a university student from Bahri, Khartoum North.

Denounced

Ismael’s remarks were followed by a statement from the Ministry of Interior distancing itself from his comments, affirming that the laws denounced by the public for violating human rights would not be re-instated.

Ismael was shortly relocated to another position in the Ministry of Interior and replaced by Lt. General Zain El Abdeen Osman as the new Director of Khartoum’s Police Force.

The former police chief’s remarks sparked outrage from several communities and bodies advocating for women’s rights. The National Commission for Human Rights condemned the comments in a statement, and the No to Women Oppression initiative called for a protest and held a meeting in the Public Prosecutor’s office, demanding a correction to El Hadi’s case. Thousands of people signed a petition demanding justice for the victim.

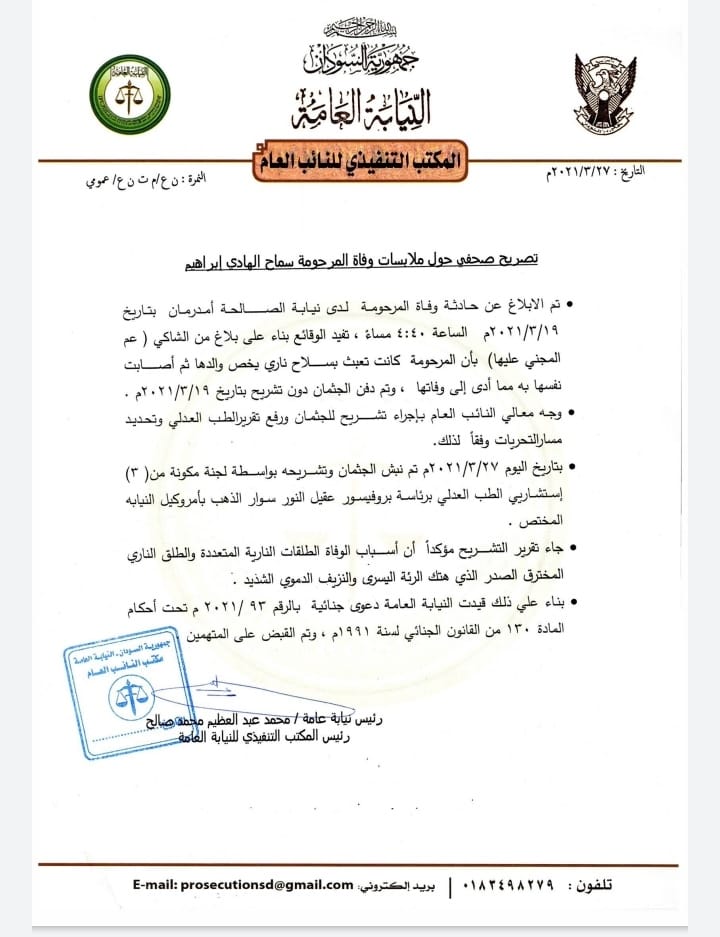

“The body was exhumed, the autopsy confirmed that she was shot three times. The cause of death was multiple bullets, one of which penetrated the left lung causing damage and severe bleeding,” a statement by the Prosecutor’s Office reads.

By the end of March, a unit within the Ministry of Social Welfare set up to combat violence against women held meetings to draft a law designed to prevent gender-based violence.

Aisha’s story

“I was assaulted by my brother one night, a year ago, as I was trying to sleep and asked him to close his room’s door because of the noise. We argued and it escalated, then he just took a wire and started to beat me viciously,” one survivor of domestic violence told Ayin. Aisha (not her real name) could not return to her job and was forced by the coronavirus lockdown to stay at home. “My mother and sister came when they heard the noise but could not stop him. We don’t have a man in the house as my father lives and works abroad.” A slim girl in her mid-twenties, Aisha felt unable to defend herself.

She said that he kept beating her with the wire for more than 15 minutes before starting to kick and slap her and then sitting on her and then knocked her head against the floor for some time. “My mum was screaming and telling him to stop, but she also got hit by his wire. My little sister was in shock and just crying. The neighbours came (two men) and removed him. I stayed on the floor unable to move for some time.”

Her brother, Aisha says, had worked with the National Security before the revolution, an environment where, under the former government of President Omar al-Bashir, security forces felt entitled to control others. “He was part of the national security undercover troops,” Aisha said. “We both participated in the revolution; we went to the protests and the sit-in. I went to bring down the oppressive regime and he went to oppress protestors.”

Covered in bruises and a swollen face, Aisha’s brother appeared remorseless and attempted to kick her out of the house, she said. Instead of putting an end to his assaults (this was not the first incident) Aisha’s mother told her to leave the house for her own safety. Despite being traumatized, Aisha refused to leave. “I told him that it was my father’s house and that I had just as much as a right to live there as he did.” Eventually, Aisha’s mother called on her uncle to remove her son.

The survivor explained that the assault took place during the first covid-19 lockdown. In order to be admitted to the hospital, Aisha had to open a police case, something neither her mother nor aunt were willing to do. With the help of friends and her younger sister, Aisha managed to file a complaint and saw a doctor for treatment.

These are not isolated cases, it’s a system of violence”

— Muhammed Osman, Human Rights Watch

“My mother refused to testify, but my sister stood by me and gave her statement to the police. I felt betrayed by my mum’s behaviour, but to be honest, the way she brought us up and how she favours our brother was the initial drive to this violence,” Aisha explained. The violence started as early as 7th grade when her brother was 12 years old. At the time, Aisha says, her mother warned her to heed her brother since he could beat her. “He assaulted me for the first time right after my mother uttered this sentence. My mother never truly defended me, she is a victim herself.” Aisha’s father and brothers were violent and, according to Aisha, her mother wanted “us to be as submissive as she and her sisters were.”

Family members and police alike allow such cases of domestic violence to take place, according to Aisha. Police never pursued her case, claiming arrests could not take place during the Coronavirus lockdown. The brother eventually returned to his father’s house after spending some time at their grandparents’ residence, Aisha said. They do not speak to each other. Aisha is still determined, however, to follow up on this case –fearing he will one day target her younger sister.

Systematic tyranny

Sudanese lawyer Mohamed Osman from the global human rights advocacy organization Human Rights Watch told Ayin that the Sudanese legal system has no sensitivity towards women‘s rights, whether its laws or procedures. Women lack protection, Osman says, and Personal Status Laws are designed to oppress Sudanese women.

“The Public Order Law was abolished but the Criminal Law has not changed, and the social mentality goes on,” Osman told Ayin. “There is no legal criminalization of domestic violence, for example, marital rape is not a crime.” Laws regarding adultery and rape are vague –even interchangeable at times, discouraging women from coming forward. “The main issue is the guardianship system -the basis of the Personal Status Law – that gives men guardianship over women, an authority that is amplified by social norms.”

Osman thinks that the recent incidents require an immediate response. “Criminalization of domestic violence and other measures are needed, such as establishing safe shelters and building the capacity of police and prosecution authorities to handle cases with sensitivity. These are not isolated cases, it’s a system of violence”. Sudan’s laws pertaining to women’s rights, he says, are full of contradictions. “For example, it identifies the child as anyone under 18, while the legal age of marriage is ten, even though one of the requirements of marriage is consent.”

Hala El Karib, Director of the Strategic Initiative for Women in the Horn of Africa (SIHA), thinks these incidents are a result of the transitional government’s neglect of women’s rights. She told Ayin that the government fears the former ruling National Congress Party (NCP) and certain religious group’s reactions to social reform. “The NCP lasted so long, they kept telling people that they control women and girls by the Public Order Law and guardianship system. This has created social acceptance of women’s oppression over the years.”

El Karib says the current government has only made superficial changes without tackling essential reforms to the structure of governance. “These institutions are still influenced by the Muslim Brothers,” she told Ayin. The lashing campaign, she says, is designed by the former ruling party and Islamic extremists. The culture of domestic violence needs to be addressed by the current government. “Instead, they only bury their heads in the sand,” she told Ayin.

SIHA’s director points out that the former Police Chief was not removed, only re-located and no one within the civilian government spoke out against the recent domestic violence cases. The former ruling party and extremist groups have nothing to lose and face little opposition in their efforts to suppress women, El Karib said. “They are far more organized than the civilian government bodies, the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC), and well-resourced to attract youth. Our problem is that the government is not capable of making decisions.” Repeated memo submissions to the Prime Minister, justice and interior ministries calling for social change are routinely ignored, she added.

Revolutionaries ignored

Dr Ihsan Fagiri, Director of the No to Women Oppression advocacy group told Ayin that women’s rights were immediately side-lined once the revolutionary protests ended -despite women’s key contribution. “This is clear in the formation of the government and its structure; the constitutional document stated that women will be given 40% of the parliamentary seats, the Juba Peace Agreement also said 40% of the whole government. That 40% ended up being 4% as political parties did not present female candidates. Bullying against women has started to rise, it shows in the bread and fuel lines.”

Positions within the security ranks are often blurred, Fagiri said. “Military officers aspire to be presidents and policemen want to be prosecutors and suppress people.” If authorities do not protect women, she told Ayin, “they are obliged to protect themselves and it will lead to more violence and chaos.” El Fagiri was stunned by some of the public comments she and her organization received while protesting against the murder of El Hadi in front of the Prosecutor’s Office. Comments such as: “So what if he killed her? He is her father,” the director recounted.

Fagiri explains that Sudan must commit to international covenants on women’s rights and implement fundamental changes to laws. “Only signing the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) is not enough, laws must be changed in their core form. The fact that the head of police was not fired [only relocated] stands as proof that the NCP mentality remains.”

Neither the military nor the civilian side of government made any comment protesting the fact the police chief was not removed, merely transferred, she said. “This includes women in the Sovereign Council and the cabinet that participate in women advocacy activities. I hold the premier personally responsible for the silence.”