State Governors denied – challenges in new appointments

7 September 2020

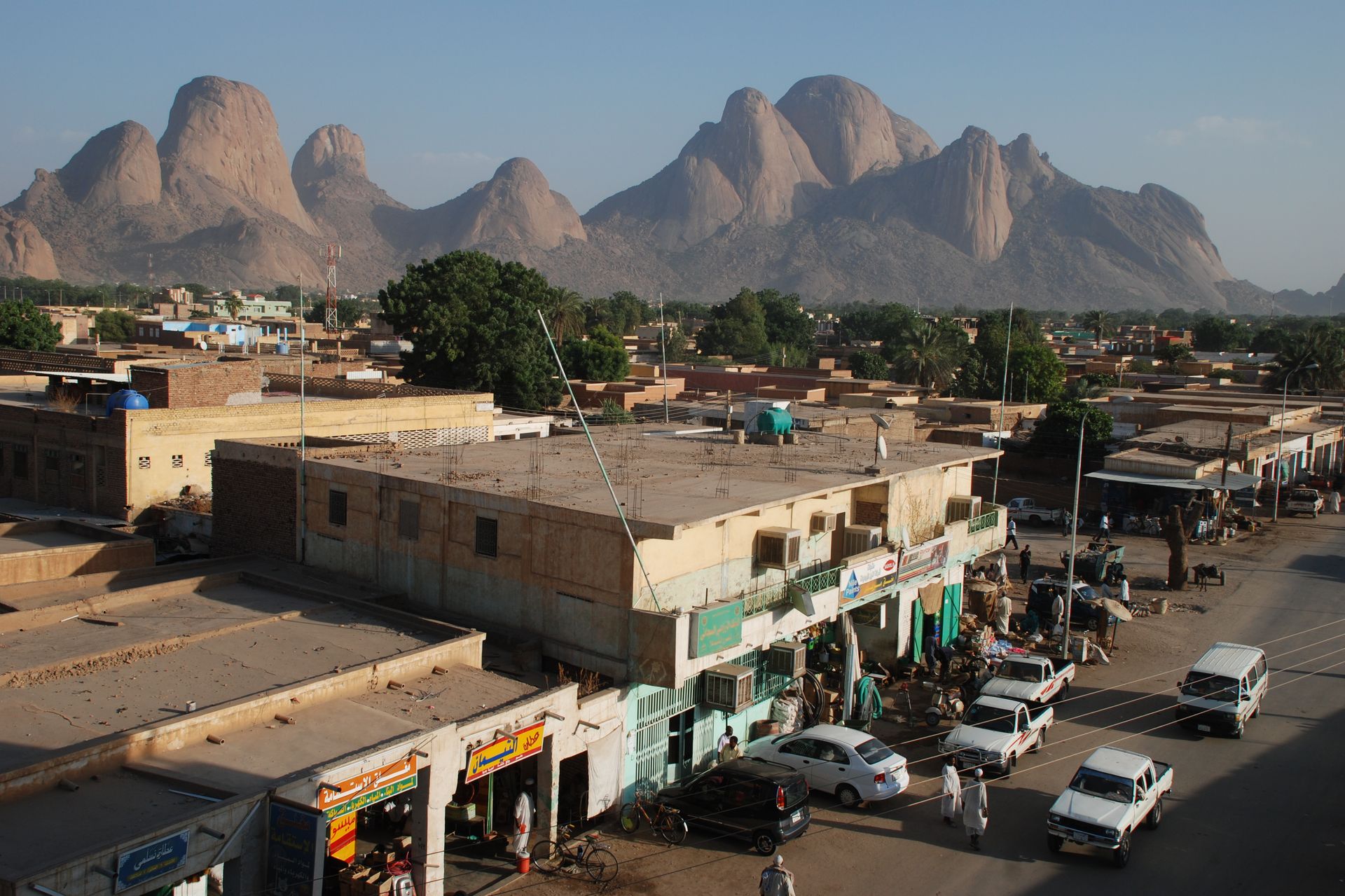

As of last week, life in Kassala, eastern Sudan, appears to slowly return to normal after a curfew was lifted and shops at Kassala Grand Market cautiously re-opened on Monday. The violent feud over the governor’s appointment appears subdued, for now.

On 4 September, Deputy Governor, Arbab Mohamed and the Head of Police, Ezzaldein Alshaikh, confirmed that life in Kassala was going back to normal. The two had a tour in the market of Kassala assuring the return of commercial activities.

The central government had not predicted the violence that erupted in three states after the much-delayed appointment of state governors took place –with events in Kassala State being one of the most restive.

Violent protests emerged in late July from opponents to the newly appointed governor in Kassala State. The protestors closed governmental facilities and blocked several roads and a bridge, including the key highway linking Port Sudan to Khartoum. Violent clashes ensued between supporters and opponents of the newly appointed governor, Saleh Ammer, inducing Kassala’s authorities to issue a curfew.

“These kind of events aren’t familiar to us living inside the city of Kassala,” said resident Halima Ahmed, adding that life is slowly going back to normal there. “People in Kassala are living together peacefully, those who participated in the riots came from outside the city –both the Beni Amer and Hadandwa who had escalated the conflict.”

By 25 August, chaos erupted in Kassala’s grand market between the new governor’s supporters and opponents with civilians brandishing sticks and knives and burning shops to the ground. At least four people were killed and about 18 were injured in what observers on the ground described as increased tension primarily between two tribal groups: the Hadandawa and Beni Amer.

State governor appointments

The transitional government and the revolutionary umbrella group, the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC), did not foresee such conflict emerging from the state governor appointments. They felt the selection process was inclusive and appointments had been publicly announced well in advance.

Sudanese Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok had appointed civilian governors for the 18 states of Sudan late last July based on nominations from the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC). “The meetings to select the governors included FFC, civil society and state actors, along with some religious leaders and academics, in addition to senior executives and consultants of the prime minister,” said FFC member Ibrahim al-Sheikh, claiming they gave the premier full liberty to choose from the list they submitted.

Another FFC member, Satie al-Haj, told Ayin state citizens had submitted their lists for a preferred state governor to the FFC. “Only minor edits had been done to the list regarding Northern and Nile River State to add female nominees,” al-Haj said. Further, the appointments were made eight months prior to their assumption of office. Given such advanced notice, Al-Haj and others question the recent protests over the appointment of certain state governors. While the majority of states accepted and welcomed the new state leadership, South Kordofan, South Darfur and Kassala States, in particular, have emphatically refused their nominees.

Some Kassala residents claim the appointed governor, Saleh Ammar, is not even Sudanese and question his nationality. “The conflict in this matter is tribal, refusing the governor based on his ethnicity isn’t acceptable,” al-Haj said.

Triggered tribalism

“Kassala State has a diverse ethnical background, but the community is well-bonded and the recent events are strange to the state,” said local leader (“Omda”), Ahmed Hamid, the head of a steering committee for the Beni Amer. “The protest that closed the bridge was full of hate speech and racism and participants had their own agenda to escalate the conflict and engage in riots.”

Reports have described the conflict between the Hadandawa who oppose a new governor from another influential tribe, the Beni Amer. But according to Hamid and others, such a simplified explanation does not depict the real situation.

Hamid clarified that the Beni Amer tribe did not nominate the governor and that the FFC committee in Kassala had nominated him. Further, despite some of the opponents to the new governor belonging to the Hadandawa tribe, they are not representative of the community but represent members of the former regime, the National Congress Party (NCP) –a view shared by the newly appointed governor. “They’re afraid of being held accountable by the new governor for their actions under the previous regime,” Hamid said –pointing out that the deputy governor, Arbab Mohamed Alfadul has contributed to escalating the conflict. “What has happened in Kassala – just like what happened in many other parts of the country – represents the legacy of the previous regime that leads to the escalation of any conflict between individuals into a tribal feud,” says Mohamed Alhafiz, an activist from the area.

The legacy of the previous regime remains a concern for people, including military influences from the capital. But according to political analyst Dr Mutasim al-Haj, the military-political partnership with civilians in Khartoum should not affect the state governors. “In every state, there is a security supreme council that includes the military units, and this council is headed by the governor.”

“The only solution is for the appointed governor to come to Kassala and start his work,” Hamid said. “People should come together and have discussions about the qualifications of the governor, not his ethnic background.”

Al-Hafiz told Ayin people want a conference for all the communities in the east of Sudan to come together and discuss their concerns. “People of the east should have a dialogue about all the issues; Identity, resources, power-sharing, the relation with the capital and the relations with the neighbouring countries.”

A cart before the horse

While potential saboteurs to the state governor appointment process appear to be one challenge for the new appointments, the legislative vacuum will likely pose another, Mutasim Al-Haj says. Governors are being appointed prior to ratifying the Law of Centralised and Decentralised Governance, Mutasim Al-Haj told Ayin.

The mentioned law is set to regulate the work of states’ governments and restructure the different department within the administrations. It contains eight chapters regarding states’ affairs and legislative authorities.

Dr Mutasim al-Haj told Ayin that it was a mistake to appoint governors before ratifying the act. “The governors now rely on their personal judgment in ruling the states. The draft law was problematic in many ways and it is now subject to further editing.” The draft law provided the state governors sweeping powers over the state legislative council, “which is totalitarian and unreasonable, that’s why the council of ministers referred the law for further editing and reviewing.” The political powers and positions within the state governments also need reviewing, Al-Haj added. “The old system should be changed and the authorizations must be clearly set.”

Despite these setbacks, the majority of Sudanese agree that state governor appointments cannot be left on hold forever. For one, Kassala residents were currently struggling with a food crisis after the violence in the main market. Shopkeepers had shifted their goods to storage in order to keep their commodities safe from further plunder. “The market is open again,” Halima said, “groceries and other goods are available but the prices almost doubled since the events.”

Between refusals from citizens to working with a dearth of legal direction, the newly appointed governors certainly have their work cut out for them. “The principal challenge for all the governors of states is how to actualise the project of freedom peace and justice”, says Al-Haj.