The case of Salha – civilians as the target of war

5 May 2025

In late April, in the quiet neighbourhood of Salha, on the outskirts of Omdurman, a group of paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) fighters pulled dozens of civilians from their homes. They ordered the men, both young and old, to sit in rows before gunning them down in front of cameras.

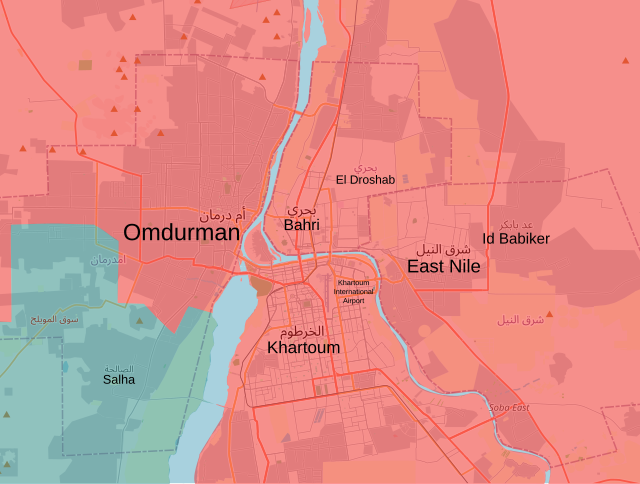

Online footage suggests the massacre took place in the Hai Al-Qe’aa Sharq neighbourhood in Salha, one of two areas within Omdurman that are still under RSF control.

Their bodies were left on the pavement, filmed, and then shared as undeniable proof of a crime that was not meant to stay hidden.

At least 30 civilians were murdered in this latest massacre, which follows a disturbing pattern of RSF atrocities since the outbreak of Sudan’s conflict over two years ago. But this attack, executed in broad daylight, recorded, and publicly claimed by an RSF commander, has sent shockwaves throughout the country. For many Sudanese, it wasn’t just another act of violence—it was a chilling reminder that no place is safe and that impunity reigns supreme.

Fear as a tactic

“This isn’t an isolated event,” says Sudanese political analyst El Bashir Idris. “The RSF employs terror as a tool of governance, using execution and ethnic targeting to instill fear.” he noted that this attack fits a troubling pattern of similar violence in the places like Ardamata, El Geneina, and eastern Al Jazeera “It’s not about winning battles—it’s about control through fear and brutality.”

Every time the RSF are defeated in one area, they carry out retaliatory attacks in another, says researcher Hamid Khallafallah. They do this partly out of frustration and partly to disprove the army’s claims that an area is safe and under their control, he added. “For instance, around Khartoum now, the army claims the area is safe and people can return—but RSF has attacked Salha and other parts of Omdurman, sending a message that SAF has not won.”

As footage from the Salha massacre circulated online, public outrage intensified. Yet the RSF’s internal messaging around the attack revealed conflicting narratives. A senior RSF commander justified the killings by claiming the victims were members of an army-affiliated militia allegedly plotting an attack on the positions held by the RSF. The RSF’s central command quickly refuted this version, denying any involvement in the incident.

Deadly impunity

Even if the victims had been affiliated with the army as the RSF suggested—a claim which remains unsubstantiated—summary executions without trial violate international humanitarian law, says Linda Bore, an expert in international criminal law with the Wayamo Foundation. The RSF’s decision to film and disseminate the footage suggests not only an intention to intimidate but also confidence in avoiding consequences. According to El Bashir Idris, the incident reflects a deep-rooted culture of impunity, where armed actors no longer feel compelled to hide their crimes.

“The executions were filmed for a reason—to send a message that no one is safe,” Idris says. The psychological impact of these public killings is central to the RSF’s strategy of control. By targeting individuals in broad daylight in residential areas and publicising them, RSF underscores its power to act without fear of retaliation, Idris added.

The risks for civilians are enormous, especially when they’re accused of supporting one side or the other. Survival has become a dangerous gamble for Sudanese civilians.”

–Laetitia Bader, Horn of Africa Director

Across Sudan, this dynamic is playing out in territory contested or captured by either force. As battles rage in cities and rural regions, both RSF and the national army routinely accuse local residents of collaborating with the enemy, says researcher Hamid Khallafallah.

These accusations—often made with little or no evidence—frequently result in disappearances, torture, and even death, he added. Civilians are thus trapped in an impossible dilemma: remain silent and risk suspicion, or engage with either side and face retaliation from the other.

Human rights organisations warn that this climate of fear is systematically eroding the fabric of Sudan’s society. Laetitia Bader, Horn of Africa director at Human Rights Watch, says the RSF’s habit of recording and sharing violent acts reflects not just cruelty but strategic messaging. “The RSF film these atrocities because they know there will likely be no consequences,” Bader explains. “This kind of impunity must be challenged, and that starts with international and regional investigators being allowed in.”

Peas of the same violent pod

The Salha massacre has also highlighted how both armed factions are increasingly adopting similar tactics. In Al Jazeera, Ayin’s investigation into the army’s conduct revealed a methodical pattern of executions targeting civilians accused of RSF collaboration. Often, the SAF picked up victims during neighbourhood raids or detained them at checkpoints, only to later find them dead, bearing signs of execution-style killings. Analysts pointed out that the similarities to RSF’s actions in Omdurman do not only indicate comparable brutality but also the normalisation of extrajudicial killings as a means of governance and warfare.

The shift from conventional battles to community-based terror campaigns shows that both factions are moving away from military logic and toward political domination through fear, Idris said. The RSF’s strategy of dominance through violence is clear, but the SAF’s pattern of retaliatory brutality mirrors this logic, creating a dangerous symmetry in how both sides engage with civilians. “It is no longer just about controlling roads or towns – it’s about breaking resistance through bloodshed and ensuring submission through trauma,” he added.

Bader notes that the stakes for civilians are especially high in contested areas. As territory shifts between RSF and army control, civilians are routinely subjected to interrogations, loyalty tests, and collective punishment. “The risks for civilians are enormous, especially when they’re accused of supporting one side or the other,” she says. “Survival has become a dangerous gamble for Sudanese civilians.”

International reaction to the Salha massacre has been largely muted, limited to statements of concern and vague calls for accountability. Sudanese civil society groups, many of them operating in exile or underground, have called for more robust international engagement—specifically, protection missions, investigative commissions, and mechanisms to hold commanders accountable. Yet so far, concrete action has been minimal.

Primary targets

Bader emphasises that treating the conflict as a conventional power struggle misses the core reality: civilians are not collateral damage—they are primary targets. “We need protection, not just documentation,” she stresses. “An international presence on the ground is critical to safeguard civilians from further harm.”

“As long as armed groups are allowed to operate with impunity, massacres like the one in Salha will not only continue but multiply,” Idris said. “The footage from Omdurman was not an anomaly—it was a warning.”

El Bashir Idris concludes that justice must become a central pillar of any future peace process. “Unless accountability is prioritised over political calculations, atrocities like those in Salha will remain the rule, not the exception.”