From liberation to persecution: Sudan’s army recapture of Al-Jazeera State

26 February 2025

While relative peace and signs of development are returning to Wad Medani, the capital city of Al-Jazeera State, security forces continue to target those within the city and across the state. The Sudan Armed Forces [SAF] and allied militias are routinely accusing civilians of collaborating with the Rapid Support Forces, often singling out ethnically African communities as well as anyone associated with the voluntary committees who support the war-affected.

On 11 January, Sudan’s army entered the central city of Wad Medani and pushed out the paramilitary RSF who occupied the city for 13 months. By 1 February, the Sudan Shield Forces, a militia aligned with the army and led by Abu Aqla Kaikal, asserted control over the towns of Tamboul, Rufaa, Hassahissa, and Al-Hilaliya.

During RSF’s rule, the state witnessed widespread atrocities, including mass killings, displacement, and sexual violence—amounting to war crimes and crimes against humanity. The Sudan Armed Forces [SAF] return to Al-Jazeera State was largely welcomed by those who fled the violence, with droves re-entering Wad Medani in particular. But this brief respite of hope has been overshadowed by cases of the army and allied militias targeting civilians both within the capital and across the state.

Wad Medani

Local humanitarian volunteers face escalating security threats, with credible reports of their names being added to lists of alleged RSF collaborators.

Waddah*, a young volunteer in his early twenties, was kidnapped by the RSF in August and September 2024 in Wad Medani last year. During this time, his phone was stolen, his head was shaved, and he was subjected to relentless abuse. Upon his release, he made his way to the nearby town of Hassahissa. When the army forces entered Hasahissa, military intelligence re-arrested Waddah, accusing him of collaboration with the RSF. He remains under detention to the present day.

“Wadah has no connection to either the RSF or the army,” Wadded’s brother told Ayin. “He is an ambitious young man who selflessly helps others and works to serve the community without expecting anything in return.” Waddah’s brother inquired with military intelligence if they had found any evidence against his brother. While they admitted they didn’t, they still did not release him since his national identification was issued in an area formerly under RSF-control. “This is our army, judging people based on their region, skin colour, appearance, and tribe, all while fighting under the banner of a so-called war of dignity,” he added.

Authorities within the army-controlled area routinely target anyone working in civil society or formerly in the resistance committees, youth-driven civil movements that helped oust former dictator Omar al-Bashir and called for civilian rule. Members of the former regime are on the lookout for anyone who had been actively part of the revolution led by the resistance committees in Wad Medani, says Maab*, a former resistance committee member. Even the checkpoints set up inside the neighbourhoods treat citizens harshly and are suspicious of the youth in particular, she said. “Anyone who does not have a national number from the state of Al-Jazeera as proof will be deported,” she added.

Since the conflict began in April 2023, at least 57 members of the volunteer network have been killed

Aid arrives, insecurity continues

Earlier this year on 22 January, the World Food Programme (WFP) managed to deliver much-needed aid to Wad Medani, the first time in over a year. Four barges loaded with 1,000 metric tons of WFP food assistance for 80,000 people arrived in Kosti via the White Nile River from the South Sudanese town of Renk. In late February, two more WFP aid shipment came through, providing support for another 100,000 residents.

This shipment was a huge relief for Mustafa*, a volunteer who helps in the communal kitchens in Wad Medani. But even though hunger is their greatest challenge, they also face security challenges, especially in terms of movement. “We know that we are exposed to danger from both sides and that volunteers all over Sudan are threatened with death, but we do not have the luxury to give up this work,” he told Ayin.

“The primary challenge in Wad Medani is the fragile security situation,” WFP Sudan Head of Communications, Leni Kinzli, said. Adding that the area is still tenuous, with active fighting occurring in parts of Jazeera State. For international organisations to reopen their hubs or offices, thorough checks for explosives and landmines are essential, Kinzli said. Looking ahead, WFP is preparing additional aid convoys to Wad Medani from Kosti and Port Sudan to assist more families in dire need.

Remnants of war

While many displaced return to Wad Medani, the situation remains precarious due to the presence of the remnants of war, including unexploded ordnances. Last month, ammunition remained scattered across roads and residential neighbourhoods. Ahmed*, a recent returnee to Wad Medani says the city’s streets continue to have burned military vehicles that have not been removed; some of the vehicles have boxes of ammunition and unexploded projectiles in them.

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) urged “residents to exercise caution when near dangerous areas and not to pick up or touch any foreign objects.”

A neighbour returned to his home and started a fire for cooking on the ground. This triggered an explosion of shrapnel and unexploded ordnance, striking him in the leg and hand due to the intense heat, Ahmed said. “We also heard about an incident where a driver was killed in his vehicle by a landmine explosion in the Al-Farijab area.”

Mass return

Despite these dangers, many of those who fled Wad Medani have decided to return to their homes, escaping the harsh reality they lived in whiled displaced. According to Adam Ali, an employee at the land port in Port Sudan, at least five buses leave Port Sudan daily to Wad Medani. Some passengers pay their tickets, and other buses move with money from charitable organisations. “Most of the displaced people want to return to their homes, even those who did not reside in shelters,” he added.

From Kassala, Kawthar Abdel Rahim packed her bags and was on her way back to her home in Wad Medani, which she had been away from for a little over a year. She was only waiting for some money from a relative abroad, so she could pay the bus fare.

“I will return to my home in Wad Medani, no matter what the situation there is, it will not be worse than the harsh reality we live in in the displacement camp in Kassala,” she told Ayin. “We have lived a year of hell and various tragedies, from diseases and hunger to the absence of health care. Our lives have almost stopped during this period, so we have to leave this situation as long as there is security and stability in our area.”

Tayba village

While cases of insecurity by the army and allied militias may be decreasing within Wad Medani, residents say, outside villages face a very different, destructive story. The international human rights organisation, Human Rights Watch (HRW) has released a damning report accusing the Sudan Shield Forces of deliberately targeting civilians on 10 January 2025 in a brutal attack. According to HRW, the assault on Tayba village left at least 26 people dead, including a child, and many others injured.

HRW interviewed eight survivors, analysed satellite imagery, and verified videos and photographs showing bodies of victims, fire damage, and mass graves. A local committee confirmed 26 deaths most from Tama, Bergo, and Mararit ethnic groups, historically marginalised farm workers from Western Sudan known as “Kanabi”. Other Kanabi communities have also come under attack in recent weeks.

“Armed groups fighting alongside SAF have carried out violent abuses against civilians in their latest offensive in Jazeera state” said Jean-Baptiste Gallopin, HRW’s Senior Researcher. He called on Sudanese authorities to investigate the atrocities and hold Sudan Shield Forces commanders accountable.

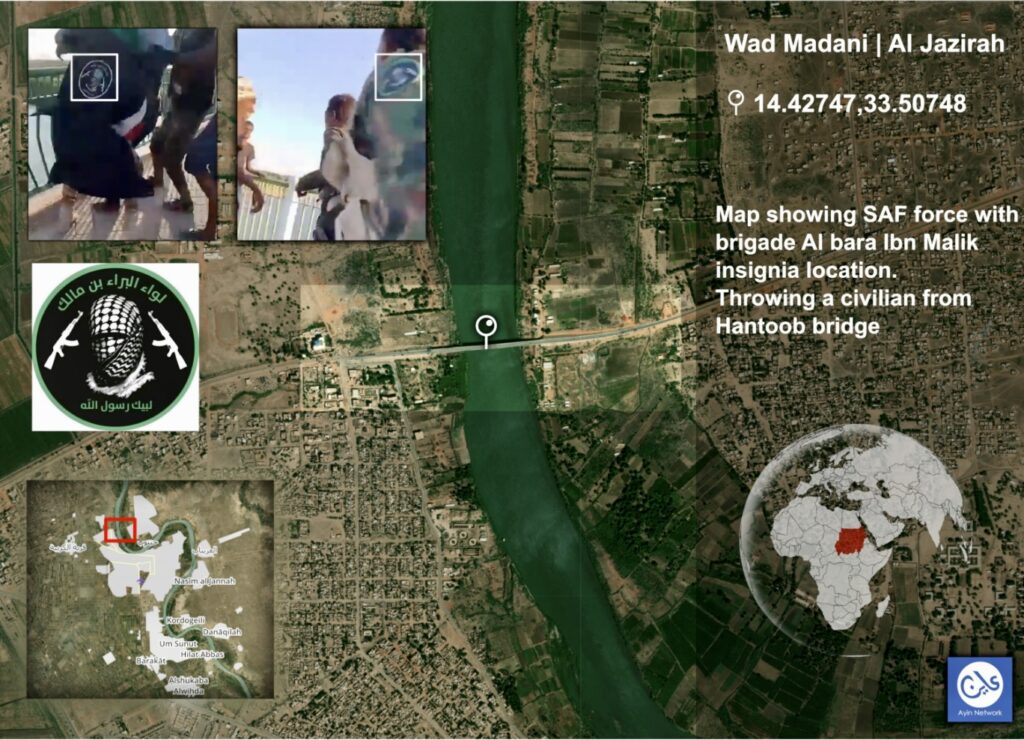

The attack was part of broader wave of violence by SAF-aligned groups, including the Islamist al-Baraa Ibn Malik battalion and local militias, targeting communities perceived as RSF supporters.

Tayba testimonies

Witnesses described Sudan Shield fighters—whom they identified as Arab—storming the village in Toyota Land Cruisers mounted with heavy machine guns, shooting indiscriminately at men and boys, and setting homes ablaze. A second wave of violence followed as villagers buried their dead, with attackers going door to door, executing men and looting property, including 2,000 cattle.

A 60-year old survivor recalled being shot at close range after armed men in green camouflage ordered him to stop. Another witness said the assailants shouted racial slurs like “you slave!” as they fired. Women were threatened and interrogated about their husband’s whereabouts, with fighters boasting about their leader, Abu Agla Kaikal.

Witnesses reported that the attackers’ vehicles bore the words “Sudan Shield” and carried the group’s emblem, reinforcing evidence of their direct involvement. Survivor’s emphasised that the village had no weapons and did not resist, yet was mercilessly targeted.

Jaafar Mohamden, the General Secretary of the Kanabi Congress, has condemned the recent attack on Kombo Tayba, attributing it to deep-seated racial and ethnic discrimination. According to Mohamden, the attack was not just an act of violence but a deliberate attempt to expel the Kanabi population and seize their land. He pointed out that Kanabi communities hold rightful ownership of agricultural land in the Jazeera Scheme and other farming projects across central and eastern Sudan.

“This attack is part of a broader campaign to displace the Kanabi people, particularly in Central Sudan, by framing our demands for justice and equality as a threat, they seek to delegitimise our rightful claim to citizenship and land,” Mohamden told Ayin.

Abu Aqla Kaikal: Sudan’s next Hemedti?

The rise of Abu Aqla Kaikal, commander of the North Shield militia, signals a dangerous shift in Sudan’s conflict dynamics. The commander is known for his violent record in Al-Jazeera state, both during his time as the senior RSF commander and after defecting to the Sudanese Armed Forces. Kaikal’s growing influence, analysts say, raises fears that the SAF is cultivating another militia leader to carry out violent attacks on their behalf. The same tactic was used under the former regime of Omar al-Bashir that helped develop the current RSF leader, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (aka “Hemedti”). Kaikal’s forces, accused of ethnic violence, particularly against Kanabi communities, have operated with increasing impunity, mirroring the early days of the RSF’s expansion.

“The growing influence of Sudan Shield militias follows the same mindset that the army has fostered for years,” Mohamden said. “Creating parallel forces outside the formal military structure, the army itself is the factory producing these militias, which operate beyond the law.”

Calling for accountability

Ayin contacted the Sudan Shield media office for comments on allegations of ethnic targeting of the Kanabi community in Al-Jazeera state. However, no response was received by the time of publication.

Similarly in previous research, Ayin analysed several videos documenting abuses by SAF and its allied forces, successfully geolocating two of them to Wad Medani.

In his first remarks on the reported atrocities in Wad Medani, Sudanese Armed Forces Commander-in-chief General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, stressed that the military is not a militia. He called for adherence to the law and warned against vigilante justice. SAF later announced an investigation into the abuses, dismissing them as isolated acts.

Ayin contacted the SAF spokesperson to inquire about the findings of the investigation launched into the atrocities committed in Al-Jazeera following the recapture of the state, and when the results would be publicly published. However, no response was received by time of publication.