Sudan’s gamble: Devaluating the Sudanese Pound

The head of the Central Bank of Sudan, Mohamed Al-Fateh announced in a press statement last week of their intention to address all issues related to foreign exchange transfers, in addition to complainants made by people following the exchange rate amendments made last week.

Opinions remain divided over Sudan’s 21 February decision to devalue the Sudanese Pound – some view it as a necessary step to curb parallel market operations and encourage foreign investment, while others foresee further hardship for citizens amidst rampant inflation and price hikes.

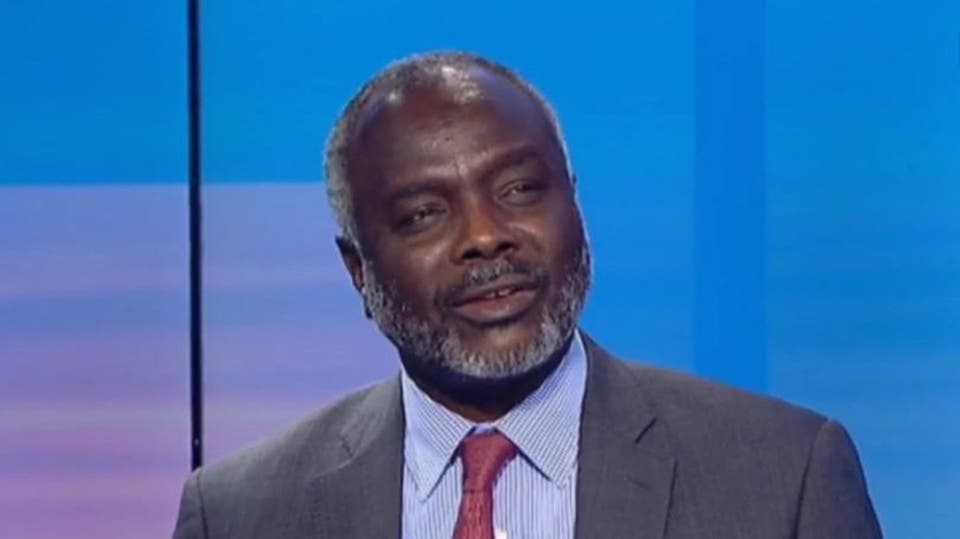

Sudan’s new Finance Minister, Dr. Jibril Ibrahim admitted on Tuesday that there are problems facing banks in the country regarding international transfers as the country had effectively ceased dealing with international and regional institutions for a long time. He did praise, however, the public’s reaction, both at home and abroad, to the government’s latest decision to unify foreign currency exchange rates, saying that people’s cooperation went beyond their expectations. A Twitter hashtag, #Transfer you money though bank, for instance, has been trending in Sudan’s social media since last week.

“Before this rule, there was no foreign exchanges taking place in banks – how could there be? In the banks, you received 55 Sudanese Pounds, in the parallel markets – maybe six times that,” says Hassan Asim, a trader in Khartoum. “So all transactions took place in the streets while banks remained empty.”

The official exchange rate for US Dollars went from 55 Sudanese Pounds to 375 as the government attempts to keep up with parallel, black-market dealers and encourage more foreign money reserves entering Sudan’s beleaguered banking system. Devaluing the currency and balancing exchange rates comes as a precondition for much-needed future foreign funds and loans the government is relying upon to conduct economic reforms.

In a press conference held to announce the decision, Minister Ibrahim informed the press that this action only comes within the governmental effort to control the parallel market, denying any foreign intervention in the decision. The newly appointed minister did concede, however, that foreign support necessitated this step. “They told us if you took this step, we will support you to lighten your debt of $US 60 million and give you grants and developmental loans. That is why we unified the exchange rate,” he stated to the press.

Floating the currency may have worked. The Bank of Khartoum declared a week into the new arrangement that the total foreign currency purchases from 21 – 25 February reached $10 million, a record increase according to the announcement.

“Sudan needs this process to work essentially because of its debt to the World Bank,” a statement from The Central Bank of Sudan (CBOS) reads. “Sudan needs to qualify to benefit from loans as part of the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries ‘HIPC’ initiative, which helped many African countries.”

Several economists Ayin spoke to concur the steps were necessary but, like past fiscal policies, needed to be implemented gradually with measures in place to protect citizenry. Many writers for local press criticized the move as well, and the way it was implemented.

Foreign Pressure

But the measure is only a partial solution, economist Dr Khalid El Tigani told Ayin, which places too much confidence in foreign aid solutions. The government is relying on foreign funds promised by the global community with conditions set by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the economist added, whereby amounts and timing are politicized and hardly guaranteed.

“This might very well backfire and lead to social and political instability. The government should have aimed for political stability followed by a national economic reform programme,” he says, adding that Sudan is very rich in resources, but the government neglects national investments to look for solutions from abroad. The measure will not be enough, El Tijani says, since the core of Sudan’s economic woes stem from a massive budget deficit and mass inflation triggered by the government’s attempts to handle it. “They inherited an inflation of about 53% and now it’s 300 percent,” he told Ayin. “[State] expenditure exceeds revenues by about US$ 4 – 5 billion and the expenditures are expected to get higher now after the peace agreement.” Nevertheless, Tijani adds, the government had to do something to curb the parallel market. “The government had no other choice,” concedes Tijani. “The awaited [foreign] funds were to serve as a cushion to facilitate this critical step that will leave most of the Sudanese people in hardship.”

IMF’s Program

But the devaluation of Sudan’s currency is not a split decision and should not come as a surprise. Last year, Sudanese authorities did sign an agreement with the IMF that resulted in the Staff Monitored Program (SMP) to which Sudan has committed to carry out several economic modifications, including lifting subsidies. The government, however, could not execute all the needed actions by the end of 2020 and failed to receive any of the promised funds.

The deadline for implementing the SMPs will be in June, according to the agreement, whereby the IMF will send evaluators to review Sudan’s progress. Interestingly, even the IMF is wary of the effects of devaluing Sudan’s currency vis-à-vis the public. “While there is broad agreement between the authorities and staff about the key reform priorities, public tolerance for painful reforms is fragile given prolonged economic hardship,” an IMF October report reads. “Notably, donor financial assistance has been well short of the amounts needed to facilitate gradual orderly adjustment. Hence, risks to the SMP are high.”

This is not the first time Sudan has attempted to devalue the Sudanese Pound in order to compete with parallel market traders, El-Tijani says. “The same scenario was implemented in 2018 by Mutaz Musa, former finance minister under [former president] Omar al-Bashir to attract businesses, expatriates and exporters – but it failed as the central bank could not keep up with the parallel market. Now the government is relying on foreign funds and trying to attract the transfers of expatriates”, he told Ayin.

|

“ “The awaited [foreign] funds were to serve as a cushion to facilitate this critical step that will leave most of the Sudanese people in hardship“. – Dr Khalid El Tigani, economist. |

|---|

Sudanese expatriates abroad do send large amounts of money yearly to the country using parallel market dealers or commercial exchange services. The government is trying to land those transactions through the official banks. On 2 March, authorities announced during a press conference 23 incentives the government will offer expatriates to encourage money transfers via Sudanese banks.

“Since the new decision, I started to use banking services to exchange dollars sent by my husband. I feel like we have a duty to participate and do the right things, not just complain about the weak performance of the government”, says Khartoum resident Sana Abdul Majid, adding that she would appreciate it if banks improved their services to avoid time wastage and attract more investors.