The paths of return: Sudan’s former regime and Islamist allies

9 April 2023

While members of the former ousted regime, the National Congress Party, (NCP), are attempting to sabotage the current political dialogue between political parties and the security forces, these efforts may be negligible given the internal divisions within the former ruling party.

Political parties under the Forces for Freedom and Change – Central Council (FFC-CC) have attempted a civilian-military negotiation to end the October 2021 military coup and form a new civilian-led government. The FFC-CC leads the signatories of the Political Framework Agreement (FPA) with coup generals Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and Mohamed Hamdan “Hemedti” Dagalo, who claim a final agreement will be finalised this month.

Analysts, however, believe key Islamist groups linked to the former ruling party pose a serious threat to the democratic transition, having ramped up their public threats against authorities over the past month.

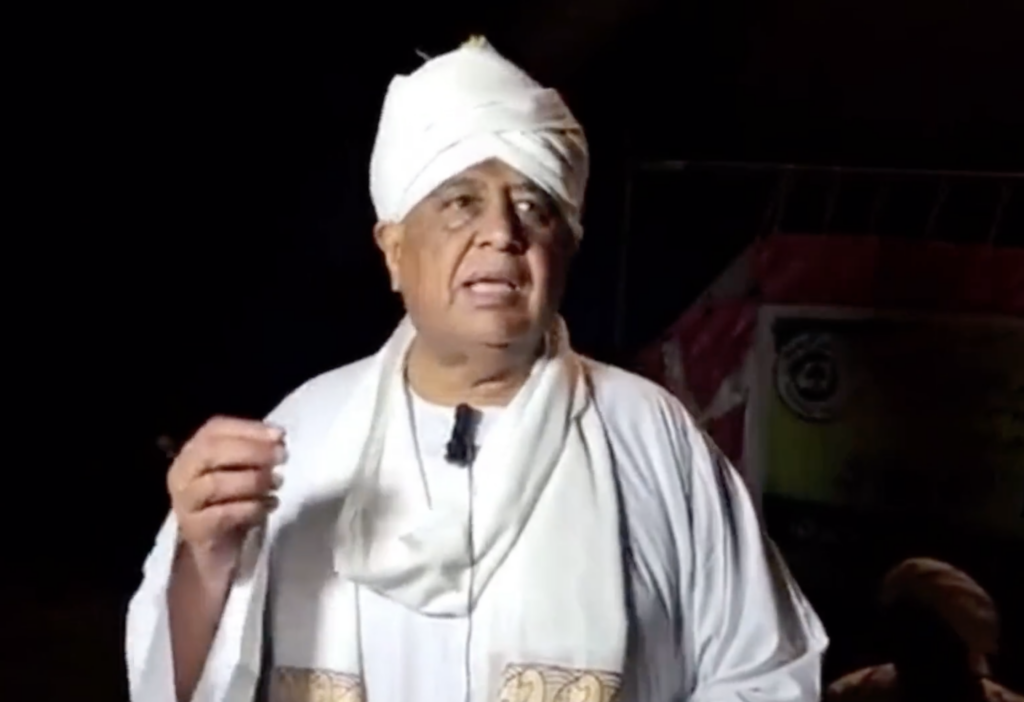

Former NCP Head Ibrahim Ghandour spoke recently at an iftar, where he referred to a broad base of Islamist support in Sudan ‘waiting for the signal to move’. Similarly, the former prime minister under the NCP government, Muhammad Tahir, threatened an armed insurrection against the framework agreement while addressing an iftar in Port Sudan. “Today we are more capable than yesterday of carrying arms and taking our rights into our own hands. Tomorrow, Sudan will witness new stages, in which there is no place for the framework or anyone else.”

Just last week, a court in Khartoum pressed terrorism charges against Islamist Naji Mustapha Badawi for his appearance in a social-media-driven video of himself, backed with masked, armed men, threatening violence against authorities if they normalised relations with Israel.

Another NCP affiliate and Secretary-General of the Sudanese Islamic Movement – Ali Karti – recently made an unexpected public appearance at a speech in Gezira State, central Sudan. Karti, who is understood to maintain close relations with Islamists in the army, was previously the subject of an arrest warrant in relation to alleged involvement in the 1989 coup and had assets confiscated in an earlier crackdown on members of the former regime.

In February, a relatively new militia calling themselves “Sudan Shield”, started openly recruiting and moving into major cities in the country, including the capital. According to military sources, the militia is directed by military intelligence and led by former Islamist army officers under former president Omar al-Bashir’s regime.

The public-facing statements of the NCP and Islamists, however, do not imply political harmony behind the scenes. Several diverse sources reveal to Ayin a web of interlocking forces, equally rivalrous as symbiotic, that have coalesced the NCP and Islamists into three relative centres of influence. Each centre, with its own strategies and constituency, possesses a distinct vision for its own return to power.

The Karti – Burhan Alliance

The primary centre of influence focuses on a puppet alliance forged between Ali Karti, former head of the Islamist Popular Defence Forces (PDF) and Minister of Foreign Affairs, and coup leader General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan.

Karti was side-lined by NCP leadership during a post-2015 dismissal as Minister of Foreign Affairs – a position subsequently granted to his political rival – Ibrahim Ghandour – yet remained an influential leader among wider groups of Sudanese Islamists. He was elected Secretary General of the Sudanese Islamic Movement (SIM) during a secret meeting with the Islamic advisory body, the Shura Council, in June 2021 on a farm near Khartoum.

The Sudanese Islamic Movement pre-dates the formation of the NCP and serves as an umbrella body for multiple constituent Islamist groups. A civil society source describes the “longstanding” rivalry between Karti and Ghandour as emblematic of the lack of a full alignment between Sudan’s Islamic movement and the National Congress Party. Whereas Karti had historically prioritized the broader interest of the Sudan Islamic Movement, Ghandour cemented his power solely within the former ruling party apparatus, the source said.

Although NCP interests and the SIM often converged, the two entities held divergent positions during the NCP’s 1999 split from Islamist Hassan al-Turabi and his Popular Congress Party (PCP). In the years prior to the 2019 revolution, senior Islamist leaders had become increasingly willing to abandon Bashir –-if not the entire NCP. From the separation of South Sudan in 2011 along with harsh international sanctions tied to Bashir’s ICC arrest warrant and the US state sponsor of terrorism list, Sudanese Islamists started to view Bashir as a liability. The Sudanese Islamic Movement held Bashir responsible for the 2013-2017 ascendancy of Hemedti, a non-Islamist, and his mercenary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) to a dominant position within the security sector.

The then-head of National Intelligence Security Services (NISS) Salah Gosh had floated multiple possibilities of an Islamist coup against Bashir. On April 11, 2019, Sudan Army Supreme Commander Awad Ibn Auf actually carried this out. The actions of both individuals – alongside former Sudan Army Chief of Staff Kamal Abdelmarouf – were later endorsed by an investigative committee of the Islamists’ Shura Council.

Gosh, Ibn Auf, and Abdelmarouf were ultimately frustrated from their full ambitions to power due to fears of Himmedti and the RSF, fleeing to Egypt in the immediate aftermath of the revolution. An informed source tells Ayin that SIM leadership remains primarily threatened by Himmedti, a tension that was notably showcased in an August 2022 verbal confrontation between Karti and Himmedti in Omdurman.

A leading member of the FFC-CC, Yasser Arman, publicly alleges that Karti developed the plan for the October 2021 coup at an earlier June meeting with the SIM Shura Council. A source familiar with the meeting claims Karti reasoned that the army leadership could be motivated toward a coup given looming fears of criminal justice for historic crimes carried out by the military. The SIM and Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) also shared a common interest to impede the transitional government Tamkeen committee, an organisation that attempted to recover assets from Islamist financial holdings and threatened the seizure of military-industrial companies. The same source added that some leaders in SIM rejected partnering with Burhan, claiming he lacked hard-line Islamic beliefs. Karti, however, calculated that Burhan could serve as the public face of a carefully reframed “military takeover” to shield SIM from overt responsibility.

But a direct link between the SIM and Burhan’s October coup is difficult to confirm given a leaked SIM report claiming the military coup was “unauthorised” by them. Nevertheless, since June 2020, Burhan was in communication with Karti. An informed source alleges the two spoke through intermediaries such as Husham Hussein, then deputy director of the General Intelligence Service, and Lt. Col. Mudathir Osman, Karti’s own son-in-law, who was shortly appointed as Burhan’s office secretary after the coup. Islamist Popular Congress Party figure, Abu Bakr Abdel-Razek, corroborated in an early 2022 interview that some PCP members, including then-acting PCP leader Adam Rahama, had participated in the coup arrangements and some “were even notified of the zero hour”.

Further, after the military coup, Burhan quickly mobilised 3,000 known Islamist cadres to staff civil service positions in his coup authority – allegedly provided to him by an “established party with a broad base that stood behind [the coup].” Hundreds of NCP members were returned to key institutions such as the central bank, judiciary, state broadcasting and other government ministries – notably, Karti’s wife, Amira Gurnas, was returned to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Security and intelligence posts were likewise re-staffed with known Islamists: e.g., Military Intelligence Chiefs Gen. Abdel Nabi al Mahi and Gen. Abdelmonim Jalal, General Intelligence Director Ahmed Mufaddal, and a number of questionable re-shuffles in the army.

Whether Karti maintains significant influence over Burhan remains up for debate. One civil society source speculates this alliance only serves as a temporary vehicle for the SIM’s slow creep into key political positions. But others such as Yasir Arman and Sudan analyst, Jonas Horner, believe Islamists are plotting to contest post-transition elections. Burhan, holding formal power in the meantime, even remains uncertain regarding his own future relationship with the SIM, having issued stern warnings against Islamist interference in the affairs of the state and disbanding historically Islamist-controlled unions in 2022.

The Kober Prison Group

A secondary centre of influence focuses on the top players directly within the NCP’s political apparatus – many of whom were imprisoned immediately or in the months after the revolution. Termed the “Kober Prison Group”, these leaders include former president Omar al-Bashir, former vice presidents Ali Osman Taha and Bakri Hassan Saleh, former minister of defence, Abdelrahim Hussein, former security chief Nafie Ali Nafie, former speaker of parliament Al-Fateh Ezzedine, former governor of North and South Kordofan Ahmed Haroun, former Oil Minister Awad al-Jaz, among others.

Senior NCP leadership has been historically plagued by political infighting but nevertheless shares a common fate under the current circumstances. Twenty-seven of these individuals face charges in the domestic judicial system –some are contending with multiple charges, and innumerable instances of corruption. Under Sudan’s criminal law, some defendants may face the death penalty if convicted. The Kober Prison group is consequently described as a “desperate” coalition seeking to free themselves through any means necessary.

The Kober group is additionally bound in shared distrust toward the Karti-Burhan alliance, believing themselves to have been sacrificed to bear accountability on behalf of historical crimes of the entire Islamic Movement. Former NCP Minister of Culture and Information, Amin Hassan Omar, described the imprisoned leaders as “irrelevant” in the June 2021 SIM Shura Council meeting, implying an unwillingness to seek their release. Burhan distanced himself from Bashir’s regime in November 2022 by ordering the return of Bashir and Hussein and a number of former Bashir aides from Alia Hospital to Kober Prison. Despite fully controlling the judiciary after the October coup, Burhan has allowed trials against Bashir and his cohorts to continue, ostensibly to provide token satisfaction toward popular demands for the dismantlement of the former regime.

On July 11, 2019, in a coup attempt later deemed “unauthorized” by the SIM Shura Council, Army Joint Chief of Staff Major Gen. Hashem Abdel-Muttalib led three other officers and 12 enlisted members of the army in an unsuccessful coup attempt. An informed source tells Ayin that despite initial blame – and possible arrest – being placed on Karti and senior SIM leader Zubeir Ahmed El Hasan, it was actually Karti who had prior advised Abdel-Muttalib to stand down due to the plan’s slim chance of success. The latter had nevertheless chosen to act upon instructions relayed from the Kober group.

The same source also believes that the Kober group had been alarmed by the plans between Karti and Burhan presented during the June 2021 SIM Shura Council meeting. They allegedly sought to pre-empt the October coup with a hastily organized plot of their own – hence resulting in a September 2021 coup attempt, which was similarly deemed “unauthorized” by the Sudan Islamic Movement. On the morning of September 21, Major Gen. Abdalbagi Al-Hassan Othman led 18 armoured and airborne army officers to seize several military installations and a media building before being forced to surrender in Shajara, a neighbourhood in south Khartoum. Sudanese media reports Othman to be a known Islamist and holding close loyalty to Bashir originating from his military service under the National Islamic Front.

The Kober group appears to persist in deploying escalatory, yet piecemeal, plots to secure their freedom. In late February this year, Islamist leader Naji Mustafa participated in a coordinated campaign calling for Bashir’s release, reportedly to have “summoned a group of masked armed men” while delivering a speech in White Nile State. Mustafa was subsequently arrested under an order of the Public Prosecution. Sans traction from broader coalitions within the SIM, the Kober Prison Group’s efforts remains unsuccessful to date.

The Reformists

A third centre of influence, occupying only a sliver of the Islamist base, may be characterized as reformists who are willing to adapt their political agendas in accordance with the democratic change in Sudan. Several civil society sources who grew up near well-known Khartoum Islamist families consider a generational divide between youth who have benefitted from family wealth versus hardliner elders who had been retrenched within the former regime. From first-hand experience, these sources say many of these youth have either assumed a less hard-line stance towards Islam, viewing the affiliations of their parents as a political risk detrimental to their own business and developmental interests.

Whether motivated by self-preservation or by developmental interests, the Popular Congress Party (PCP) and Ansar al-Sunna have also shown slight indications of a reformist political agenda. Both notably attended consultations surrounding the FFC-CC-led Sudan Bar Association draft constitution in August-September 2022, a gathering that had been attacked by other suspected Islamist cadres. PCP Secretary General Ali al-Hajj took a stand against alleged Islamist coordination behind the October coup by dissolving his own party secretariat and dismissing its acting leader Bashir Adam Rahma. The PCP has since signed and publicly endorsed the Framework Agreement, revealing plans of engagement in the formation of a new transitional government.

The reformist centre of influence still faces public mistrust. Resistance Committee members and others have openly called for the exclusion of PCP and Ansar al-Sunna in any form of political participation. Moving forward, the reformist centre of influence has much ground to cover in rallying internal support among other Islamist groups while bridging the lack of external trust before they can be fully accepted in the Sudanese domestic arena.

Conclusion

NCP and Islamist threats against talks of an upcoming revival of the Sudanese transitional government must be taken with a degree of nuance. Internal power dynamics, misaligned interests, and an overlapping set of actors among the three centres of influence greatly complicate the decision-making matrices of the NCP and Islamists. Adept domestic and international political strategies may carefully navigate this landscape to neutralize publicly apparent, but nevertheless disjointed threats against the path to a new Sudan.