Heritage guardians: The ongoing quest to save Sudan’s history

10 December 2025

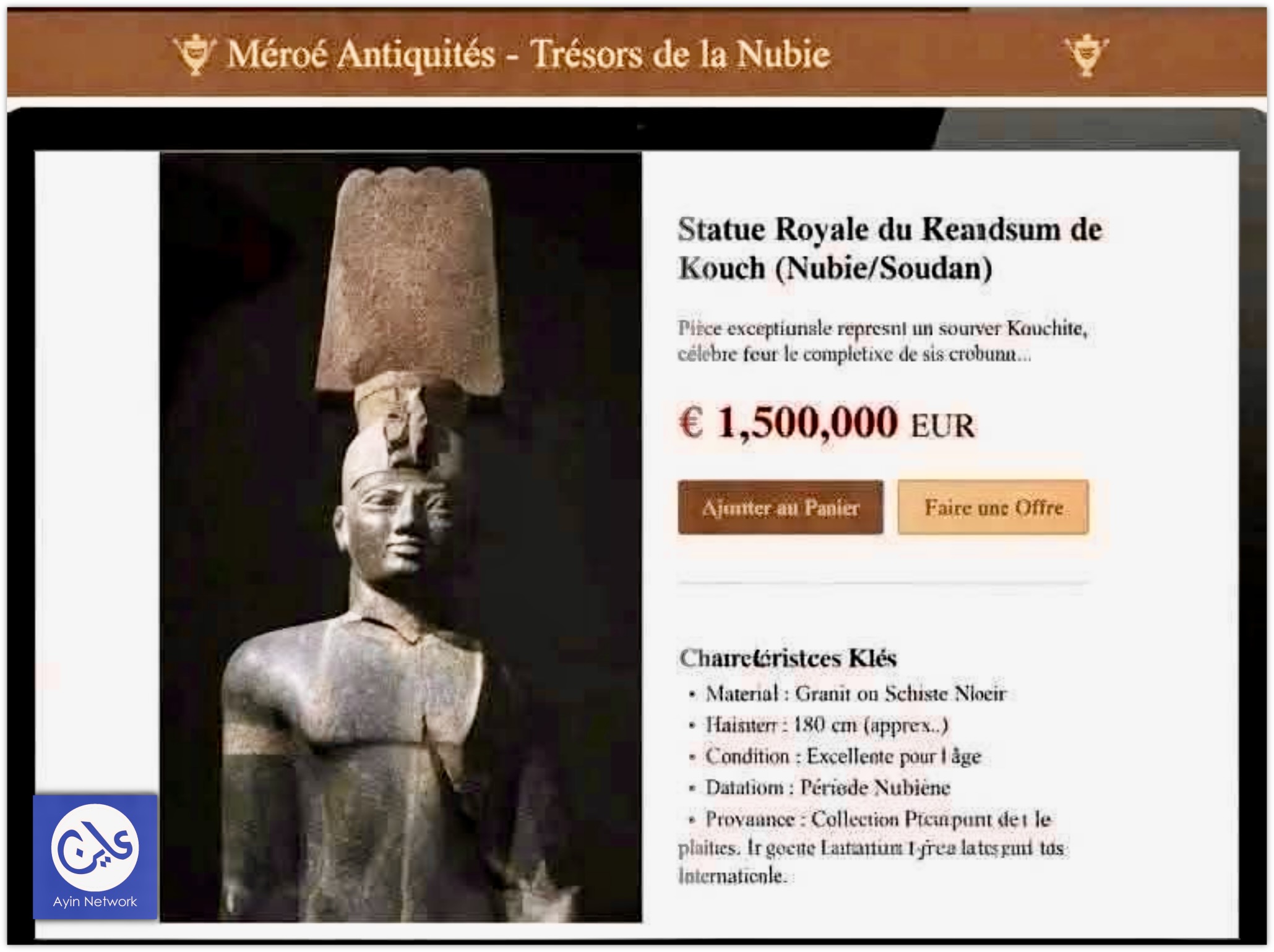

In mid-November, Sudanese social media accounts decried yet another loss rarely documented by the media – a priceless Nubian artefact was allegedly stolen and sold on an e-commerce platform. The illicit sale of a granite statue of King Aspelta, a powerful Nubian ruler of the ancient Kush Kingdom, sparked widespread condemnation on Twitter accounts.

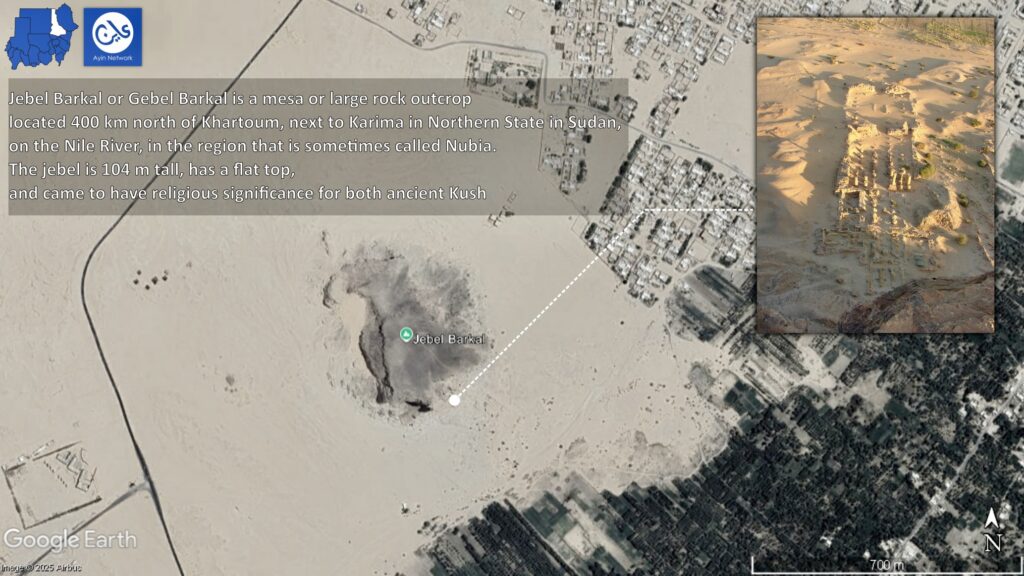

Blue Shield International, an organisation that seeks to protect cultural heritage sites, along with the Ayin investigation team, managed to defuse this painful rumour, confirming that the online listing was false. The object shown was, in fact, a well-known museum piece: the granite statue of King Aspelta, excavated from the Great Temple of Amun at Jebel Barkal and dated to 600–580 BC. The statue remains safely housed at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

This verification provided Ali Noor, the Secretary General of the Blue Shield Sudan National Committee, a small sigh of relief. But not a day goes by for Noor without a heavy sigh of dismay, as he learns of the wanton destruction of Sudan’s cultural heritage sites and artefacts.

Museums destroyed, artefacts looted

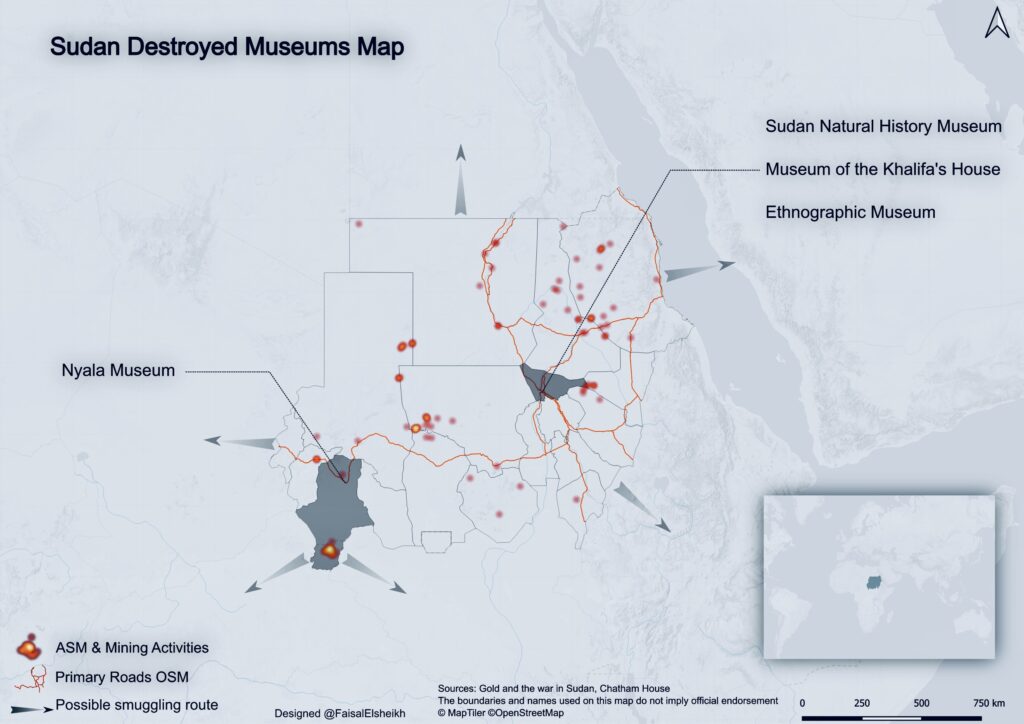

While it is impossible to gauge an exact estimate, Noor says satellite imagery and field documentation have helped them confirm that dozens of museums, archaeological sites, and heritage institutions have been damaged or destroyed, and thousands of artefacts looted. Major institutions affected include the Sudan National Museum, the National Ethnographic Museum, Nyala Museum, El Geneina Museum, and the Khalifa House, as well as multiple university libraries and national archival institutions, he said.

According to archaeologist and museum curator Dr Shadia Abdrabo in an AP interview, regional museums in the Darfur region, El Geneina and Nyala, are almost completely destroyed, while the National Museum in Khartoum – which held an estimated 100,000 objects before the war – was ransacked.

The National Museum had pieces dating back to prehistoric times, including those from the Kerma Kingdom and the Napatan era, when Kushite kings ruled the region, as well as those from the Meroitic civilisation that built Sudan’s pyramids. Other galleries showcased objects from later Christian and Islamic periods. Among its most valuable items were mummies dating back to 2,500 B.C., some of the oldest and most archaeologically significant in the world, as well as royal Kushite treasures.

Systematic destruction

To Noor, the destruction of Sudan’s historical heritage is not accidental, the unfortunate by-product of a destructive war, but a planned, systematic tactic used by the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces. “There is no credible interpretation under which this pattern of destruction can be described as accidental,” Noor says. “The RSF (Rapid Support Forces) is not only seeking military control—it is reshaping Sudan through the erasure of ethnic and historical identity. When palaces of sultans, museums of peoples, and archives of the state are destroyed simultaneously with mass killings and forced displacement, the objective is clear: to eliminate both the people and their history from the land.”

He cites the heavy damage to Sultan Ali Dinar’s Palace in El Fasher, which occurred after an RSF siege, as an example of such efforts. “This palace is not merely a historical structure—it is a symbol of Fur sovereignty, political authority, and anti-colonial resistance. Its targeting is inseparable from the wider assault on the Fur people.”

Likewise, in El Geneina, the destruction of the Sultan Bahr el-Din Palace and El Geneina Museum took place alongside the RSF’s ethnic targeting of the Massalit people. Even the director of the El-Geneina Museum, along with his entire family, was killed, Noor said. He describes the case as a stark example of the simultaneous implementation of cultural extermination and physical annihilation. “These were not incidental acts. They represent the deliberate physical and cultural extermination of entire communities from the historical landscape.”

Systematic looting

In other cases, the armed groups have looted historical sites for profit – some estimate losses of around $110 million, while others believe it to be much higher. Thefts include an entire archaeological gold collection (including jewellery from the kings and queens of the Napata era), small portable artefacts, and mummies dating back to 2500 BCE.

Satellite imagery from 2024 appeared to show trucks loaded with artefacts leaving the museum while they were under RSF control, suggesting a coordinated operation.

Noor says the RSF operates a war economy that includes the large-scale heritage looting as a direct source of financing. The historical loot is trafficked through western corridors toward Libya and Chad and through Red Sea ports under weakened state control, he said. Regional black markets, closed online trading networks, and even international auction houses eventually sell these items.

“The RSF (Rapid Support Forces) is not only seeking military control—it is reshaping Sudan through the erasure of ethnic and historical identity. When palaces of sultans, museums of peoples, and archives of the state are destroyed simultaneously with mass killings and forced displacement, the objective is clear: to eliminate both the people and their history from the land.”

— Ali Noor, Secretary General of the Blue Shield Sudan National Committee

Blue Shield International, among other actors such as Dr Abdrabo, are working tirelessly to identify and map out the destruction of Sudan’s heritage in a bid to track down stolen artefacts and maintain as much of Sudan’s historical record as possible. To Noor, this work is pivotal for Sudan’s history and current identity.

“The destruction of museums, archives, palaces, and sacred sites is the destruction of Sudan’s collective memory itself. When heritage is erased alongside communities, what is being targeted is not only land or power but historical existence,” Noor said. “This is cultural extermination embedded within mass violence.”