Remembering El Fasher: A journalist’s account

5 January 2025

A reporter for Ayin recounts from El Fasher the final moments of the city’s fall.

In October last year, the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) conducted a siege on El Fasher, toppling the last army stronghold in Darfur, ensuring RSF control of the vast area, estimated to be the size of Spain. The process resulted in the loss of countless civilian lives and the displacement of countless more. However, accurate estimates of one of the bloodiest takeovers since the outbreak of war in mid-April 2023 remain rare. Below is one of the few accounts from our own El Fasher correspondent about his ordeal trying to cover the El Fasher story and his plight, among other journalists who tried to do the same.

Reporting in El Fasher was no easy task. Despite the grave dangers, I chose to remain in the city with a few colleagues after more than 95% of journalists had fled, as living there had become virtually impossible. The Rapid Support Forces (RSF) had infiltrated residential areas amidst a security vacuum and a catastrophic collapse of basic services such as water, electricity, and healthcare. The banking system had ceased functioning, and hospitals and markets were out of service, making reporting on the situation on the ground a daily and urgent necessity.

Amid this pressing professional reality, the Sudanese army’s military and security authorities tightened their grip on press freedom, preventing journalists from carrying out their professional duties. Caught between the hammer of threats from RSF commanders and the anvil of restrictions imposed by the Military Intelligence Branch of the Sudanese army in El Fasher, uncovering the truth and revealing accurate information was an imperative for those of us who remained, to document these events for posterity.

Military press repression

I remember in July 2024, when I wanted to interview displaced families who had lost loved ones in an RSF artillery bombardment of the Al-Inqaz neighbourhood. The RSF commanders forced these families to flee to the Shala area, where they erected tents made of tattered fabric. As soon as I started filming, a soldier from the Central Reserve Forces—a unit affiliated with the army—pointed his weapon at me and took me to the headquarters. The commander stated that filming in areas where displaced people were staying near military zones was forbidden, claiming it “served the enemy” and demanding that the footage be deleted. I refused, emphasising the importance of documentation, and after a lengthy argument, he allowed me to leave. They recounted the details of the tragedy before the footage was sent to a foreign news channel.

In another scene, after the armed forces repelled a major attack by the Rapid Support Forces, citizens went out in celebration. While I was filming this spontaneous scene, a member of the military intelligence snatched my camera and tried to take me to the Sixth Division despite my showing my press ID. I only got the camera back through the intervention of acquaintances, accompanied by threats of prosecution if the pictures were published.

This pressure prompted us to appeal to the head of the state’s Supreme Council for Culture and Media, urging him to coordinate with the military to ensure the world was informed of the facts. However, the government agencies seemed intent on silencing the press. But there was no turning back. I combined journalistic and humanitarian work by preparing and distributing meals to shelters at a time when food had completely disappeared due to the siege. It was a point where animal feed was the only available sustenance for the residents.

We launched the “Save El Fasher” campaign to highlight the suffering of malnourished children, the elderly, and the wounded, and we sent hundreds of messages to the international community to break the siege. We documented serious violations by the RSF, and we also observed the participation of members of the army and joint forces in looting citizens’ homes and selling their wooden roofs as cooking fuel.

I lost my entire home, my belongings were reduced to rubble, and I was displaced, living among the neighbourhoods, surviving on scraps, and participating in digging trenches for shelter.

The most difficult days

On October 26 and 27, 2025, the bombardment reached its peak as shells rained down upon us. After neutralising its platforms and tightening the noose around the army headquarters from three sides, the army’s artillery found itself unable to respond.

Monday, October 27, was the most difficult day; the sound of the call to prayer that is raised daily in the mosques was absent, and I had a feeling that something serious and dangerous had happened in the city. After the sound of the large explosions subsided, I left the room where I was staying and peeped through the opening of the house door, where I saw new combat vehicles standing in front of the house, which is only 500 metres north of the Joint Force Command and one kilometre south of the Army Artillery Command.

I rushed back to the room, spoke in a low voice to my cousin and told him about it. As soon as we fell silent, we heard voices and conversations in different dialects that we had never heard before, which confirmed our suspicion that the Rapid Support Forces had taken control of the city.

It wasn’t long before members of the RSF stormed a house in the first-class neighbourhood, demanding that mobile phones be handed over to them at gunpoint. They also broke the locks on the closed doors and looted whatever property they could, accusing us of being affiliated with the army and the joint forces.

Fleeing El Fasher

In the middle of the night, we decided to flee. My elderly paternal grandmother, two of my aunts, and my cousin were with me. During our escape, soldiers from the Rapid Support Forces opened fire on us. Thankfully, none of us were hit before they stopped us and looted what little money and clothing we had left.

At the western gate, I saw the army and the joint force withdrawing with all their equipment, and I realised that El Fasher had fallen completely. We lost our way, our water ran out, an old pain in my knee worsened, and my grandmother passed away while being carried on a handcart that we took turns pushing.

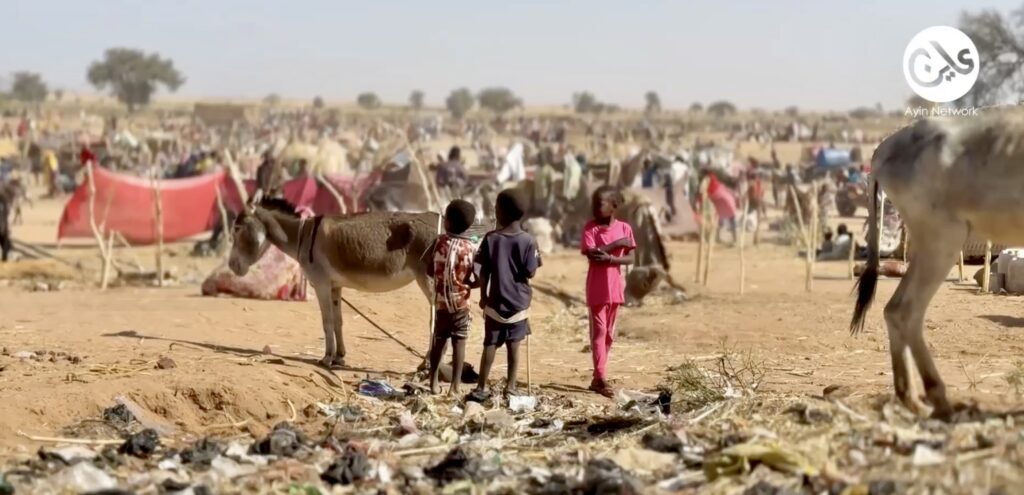

We finally arrived at the village of Qarni (40 km west of El Fasher), a camp surrounded by a large trench more than three metres deep and about three metres wide. We don’t know where it begins or ends! This camp is where the displaced people and those fleeing the horrors of war in El Fasher are crammed.

The trenches were the only means of protection for civilians from the RSF bombing of El Fasher.

Along the way, we saw the bodies of young men lying on the ground. We saw more bodies at the entrance and inside the big trench that encircled the village. While making our way out of El Fasher, the RSF would shout obscene, provocative words at us from the tops of their vehicles. The features and accents of some of those personnel were not Sudanese.

Qarni village

Upon our arrival at the Qarni village school, which had been transformed into a large centre for receiving fugitives, we saw RSF officers instructing young men to head towards a truck to be taken to the mass displacement camp in Tawila. However, I later learnt that the truck headed towards El Fasher and then to Nyala under heavy military escort. The men were being forcibly recruited into their ranks. Anyone who tried to jump off the truck was killed.

The school’s classrooms have been turned into wards for hundreds of wounded and injured people, some of whom have died, while others are receiving treatment from medical teams brought in by the Rapid Support Forces.

While I was in the Qarni area, a member of the RSF, wearing a head covering known as “kadamul,” approached me warmly and asked in a somewhat enigmatic voice, “Don’t you recognise me?” I replied no, but he quickly removed his head covering and said, “Aren’t you the person who interviewed me at the Dar al-Arqam shelter in El Fasher? Aren’t you the journalist?” I confirmed my identity to him, and he looked at me for a moment before leaving.

Fleeing again

After that moment, we decided it was unsafe for me to stay and to leave the area as quickly as possible. It had never occurred to me that the RSFs’ intelligence apparatus was capable of planting informants in the shelters, while the army’s intelligence services were relentlessly pursuing journalists.

While I write this reflection of my ordeal, I must remember those who have suffered a worse fate. In this tragedy, we lost many colleagues in El Fasher, including Taj Al-Sir Ahmed, Ahmed Mohamed, Al-Nour Ahmed, Mubarak Musa, and Mohamed Al-Fatih. Others were arrested: Magdi Youssef, Essam Jarad, and Muammar Ibrahim, while the fate of photographer Mohamed Hussein Shalabi remains unknown.

We left Qarni carrying the “forgotten” wounds of El Fasher, which was offered as a scapegoat, amid the betrayal of the state that failed to protect its civilians. The disaster of El Fasher buried all international norms and laws, and the international community failed to stop a humanitarian catastrophe that occurred in the stricken city.