Facing starvation, El Fasher residents maintain hope for a proposed ceasefire

1 July 2025

After enduring a near year-long sige by the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces on the El Fasher area, conflict displaced civilians like Amira Abdel welcomed news that a potential weeklong humanitarian ceasefire may take place to allow critical aid to enter the city.

Every day, Amira Abdel, along with hundreds of other displaced women, stands in line for hours in a residential neighbourhood of El Fasher hoping supplies from a community kitchen will not run out before she reaches the front of the long, winding queue. Some days she and her family eat one meagre meal, on many others, they don’t.

Last Friday, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, head of the Sovereignty Council and commander of the Sudanese Armed Forces, approved a week-long humanitarian truce in El Fasher to allow aid deliveries during a phone call with UN Secretary-General António Guterres.

The potentially good news could not come soon enough.

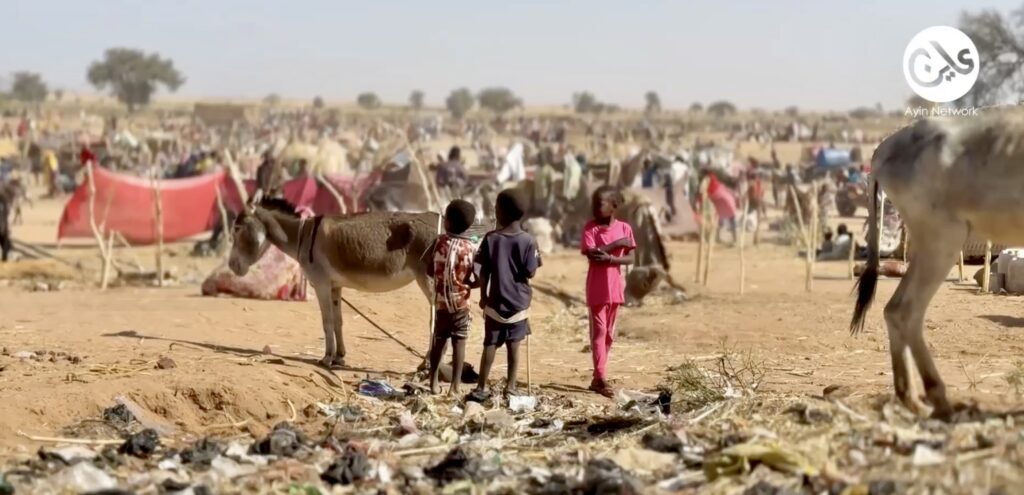

Since April 10, 2025, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have intensified their attacks on North Darfur State’s capital city, El Fasher, and the Zamzam and Abu Shouk IDP camps in North Darfur, Sudan. The Sudanese army, combined forces, and mobilised El Fasher rebels are preventing the RSF from taking Darfur’s last major city still under army control in the Darfur region.The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs estimated the population of over 900,000 in Al Fasher locality, with some 700,000 internally displaced due to escalating violence.

Will both sides agree?

The RSF position on the UN proposal for a humanitarian truce, however, remains shrouded in mystery. No official statement has been issued yet, but several advisors to its commander, Mohamed Hamdan “Hemedti,” have made statements that implicitly reject the truce. Mohamed Mukhtar El Nour told Asharq Al-Awsat that his forces had not been officially notified by the UN of a request for a humanitarian truce in El Fasher, and that his forces would not accept any ceasefire in El Fasher because the city was now empty of civilians who had been displaced to Tawila and Korma, he claimed.

“The de facto authorities in Port Sudan’s announcement of a seven-day humanitarian truce in El Fasher is motivated purely by military considerations, following the deterioration of the situation of their forces inside the city,” says Ibrahim Mukher, a member of the advisory office of the RSF commander. “We have received reliable evidence indicating that civilians are being exploited to meet the needs of these forces.”

Mukher told Ayin that the RSF are ready to cooperate with the United Nations and aid agencies “to ensure humanitarian aid reaches those in need without discrimination or obstacles, and even to secure the exit of citizens from war zones.”

No aid in months

A humanitarian worker requesting anonymity for security reasons explained that the latest siege, which came on top of a previous blockade, has worsened the crisis to an unprecedented degree. “No food convoy has entered El Fasher recently, not since the battles on January 24–25, 2025,” he said. Securing aid under the current conflict conditions has proved impossible, the source said. “Food no longer arrives the way it did during the first siege. The current situation is far worse than ever before.”

The crisis is becoming even more complicated due to attacks on aid convoys. Reports indicate that the most recent convoy headed to El Fasher was hit in an airstrike in Al-Koma village. Both warring parties have denied responsibility.

While some have managed to flee the conflict, many remain trapped inside, the aid worker said, stressing that those who stayed have nowhere else to go.

Markets are experiencing severe shortages due to supply cuts. The collapse of the local currency has pushed the prices of remaining goods beyond the reach of most residents, he added. With basic supplies stopped, goods only reach El Fasher through smuggling routes and in very small quantities, which cannot meet the vast needs of the population. “Prices have reached absurd levels,” says Adam Omer, a medical doctor from the Dar al-Salam neighbourhood south of El Fasher. “For example, a single bar of soap can cost as much as twenty-five thousand Sudanese pounds (roughly $11), reflecting massive and unprecedented inflation.”

Critical access

Nema Al-Haj, a humanitarian aid worker and member of the emergency response rooms, a volunteer-driven initiative to support the conflict-affected, says the year-long siege has severely hindered their efforts to help citizens. “Recently, all efforts to deliver food, medicine, and essential aid have collapsed due to the militia’s obstinacy and the refusal to allow humanitarian access,” Al-Haj said.

After the RSF seized control of Zamzam IDP camp, an aid worker requesting anonymity told Ayin, a vital lifeline was cut that once supplied the city with essential goods. “Previously, food and medicine reached El Fasher through a road connecting it to Zamzam, coming from Dar Al Salam. This movement relied heavily on women, who worked tirelessly to bring in necessary supplies.”

According to the aid worker, the Sudanese army’s shelling of the Turra market was not just an attack on a place of commerce—it struck the only remaining channel through which residents could access what they needed, as vehicle movement had become impossible due to the siege. “Everything now depends on animals like donkeys, camels, and horses, which move very slowly. Women would go to the Turra market to get food supplies and then endure a grueling journey back to El Fasher,” the same source told Ayin.

The siege has made every day a battle to stay alive, as the city’s residents cling to hope that aid will reach them before it’s too late.

— Abdullah Abaker, El Fasher resident

Facing acute food shortages, residents have turned to difficult and insufficient alternatives like belila (boiled grains) or ambaz (groundnut paste). Basic items like cooking oil and onions have disappeared from the markets for months at a time.

Emergency volunteer groups struggle to keep communal kitchens running, but their efforts remain very limited compared to the vast humanitarian needs, local volunteers told Ayin.

Sanaa Younis, a volunteer who fled from El Fasher to the Shangil Tobaya area, told Ayin that during her displacement, she saw an elderly woman, likely in her late seventies, fleeing along the road from El Fasher. She was exhausted and dehydrated and managed to reach an area near Shangil Tobaya, where some people gave her water and milk. Shortly after, she collapsed; they tried to get her to a hospital, but she died on the street. “This is a tragically common scene you might witness in El Fasher and its surrounding areas,” Sanaa Younis said. “The humanitarian situation is extremely dire; words cannot describe the suffering.”

Trenches of survival

When El Fasher area residents are unable to flee or safely search for food, they try to hide from the constant shellings in trenches that resemble those used in the first world war. “Today, the sight of trenches carved through El Fasher’s streets and squares has become a defining feature of the city’s new reality under war,” says El Fasher resident, Abdullah Abaker.

The trenches are especially common in overcrowded neighbourhoods, he told Ayin, where families have fled from areas seized by the Rapid Support Forces. Dug to depths of two or three meters or even deeper, they are expanded to hold as many people as possible.

“To survive airstrikes and shelling, residents roof these trenches with tree branches or zinc sheets, sometimes layering sticks topped with sand-filled sacks.” The entrances are deliberately narrowed, allowing only one person at a time to squeeze inside. This makes it harder for shrapnel or debris to reach those sheltering underground, Abaker said, but it also means families are crammed into dark, stifling spaces for hours or even days.

“People spend their days in constant fear, rushing to trenches with every explosion or drone overhead. The siege has made every day a battle to stay alive, as the city’s residents cling to hope that aid will reach them before it’s too late.”

No medicine

Prone to shelling and facing severe hunger, the medical needs of the population in the greater El Fasher area are immense, says Dr Adam Omar. But the health system in El Fasher is on the verge of collapsing, Omar says. For a year they have not received medical supplies.

“El Fasher is not asking for political support or statements of solidarity,” Omar told Ayin. “El Fasher asks for only one thing: to open the doors to life, to let aid reach its children before hunger devours them, and to break the siege before it swallows what remains of innocent lives.”