Khartoum’s silent killer: unprecedented disease outbreaks

7 October 2025

Ever since Sudan’s army retook control of the capital, Khartoum, and its sister city, Omdurman, residents thought the death toll would finally subside. Instead, the absence of any functioning health facilities has led to the silent death of civilians from diseases that have easily spread across the city.

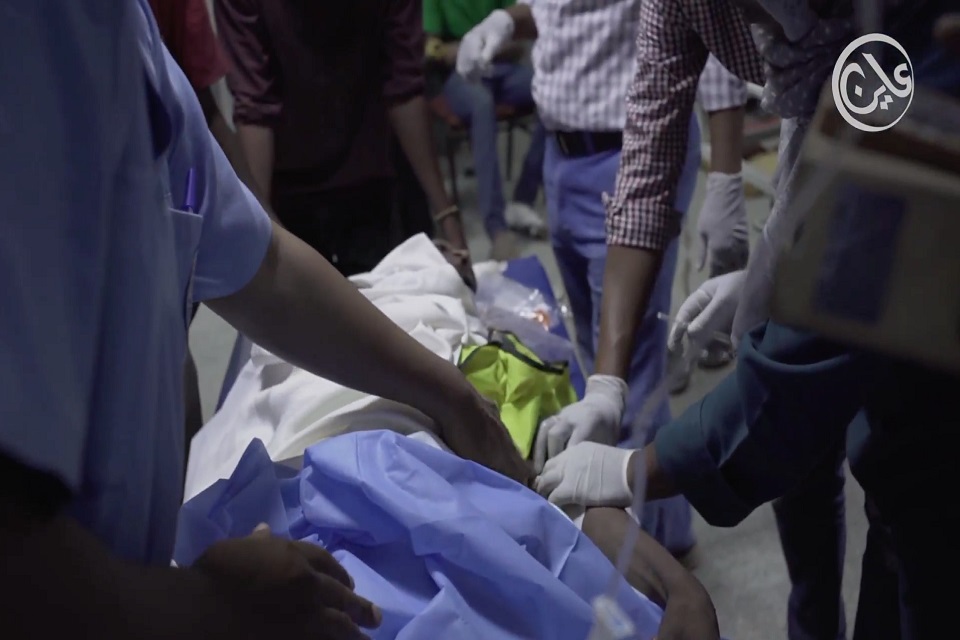

Khartoum is reeling from a severe public health emergency, local medical sources told Ayin. Disease outbreaks, especially cholera, malaria, and various fevers, are spreading rapidly; food and water infrastructure remain devastated, and health facilities are overwhelmed.

Dengue fever has exploded across Khartoum, stretching hospitals already weakened by conflict. Over 2,000 new dengue cases were recorded in a single week in September, though health officials warn that the real number is likely much higher. Khartoum State has now logged more than 14,000 confirmed cases, with fatalities rising. The UN is warning that this outbreak, coupled with cholera and malaria, is pushing Sudan’s fragile health systems to the breaking point.

Noor Atiya, a university student in Omdurman, has not left Khartoum for the past three years. She told Ayin that she survived the siege, hunger, and aerial bombardments only “by the grace of God.” But now, she said, disease has become an even harsher struggle. Since August, Noor has contracted malaria four times.

Malaria

“We are a family of six, and every one of us is suffering from malaria, severe dengue fever, or both. Even our youngest sister, who is only a year old, is sick with malaria and intestinal diarrhoea,” Noor explained.

She described the symptoms as unbearable: “You can’t walk; you can’t sleep from the pain, the fever, and the pounding headaches. You completely lose your appetite; sometimes you can’t eat for two days straight. This illness is truly dangerous.”

According to Noor, the war has left her family surviving on just one meal a day, which doctors say has severely weakened their immune systems. In Omdurman’s Al-Hara Al-Oula neighbourhood, she said, the health situation is “nearly catastrophic”. Power outages, extreme heat, and the spread of disease-carrying insects like flies and mosquitoes are making things worse.

Access to medicine, Noor stressed, is one of the biggest challenges. “You have to buy drugs on the black market because pharmacies hoard supplies or sell them at exorbitant prices. As a family, we’ve already spent nearly $200 per person, forcing us into debt with local pharmacists. Even now, we’ve only managed to pay off half of what we owe.”

The government tried to use planes to spray insecticide last August, but Noor said their efforts were ineffective. “The epidemic is bigger than that. We need house-to-house spraying, and campaigns in areas where stagnant water collects.”

Dengue fever

Reem Mokhtar is a volunteer in the community kitchens run by the youth-driven Emergency Response Rooms (ERRs) in Omdurman. Since late July, Reem began to notice cases of dengue fever. “At first, the spread was limited, but by mid-August infections were rising sharply, and in September it had become a full-blown epidemic” she added.

Reem described how the illness swept through her household and among her neighours. “There are eight of us in the house, and all eight were infected, even the baby, who is only a year and a half old. In the apartment below hers, 14 people are infected while one person died from the disease. Upstairs, a mother and six children are all sick, she added.

Electricity cuts last hours, sometimes days, in Omdurman. “Without power, it is impossible to shut the doors and windows to keep mosquitoes out,” she added. “The heat made it unbearable.” Many people even carry mosquito nets with them in a desperate attempt to prevent infection. “You see them [mosquito nets] everywhere: at weddings, in markets, and in the streets.

The family’s greatest challenge has been finding medicines and IV fluids to treat the disease. “Hospitals were overflowing with patients. A test that used to take one hour now takes three.” The price of IV fluids has recently risen by 3 – 4 times. “Even in the state-run pharmacy at Al-Nau Hospital, supplies are so limited that a patient is only given three IV bags.”

Al-Nau Hospital

Even well-established hospitals such as Al-Nau Hospital in Omdurman are struggling with a lack of access to medical supplies and health personnel. Ali Gabay, an ERR medical volunteer who has not left the hospital’s emergency ward since the early months of conflict, says the facility only admits critical cases given the influx of patients. “The hospital does not accept mild cases at all, only advanced ones – our capacity is simply too weak to take in anything else,” he explained.

According to Gabay, dengue fever has spread at an alarming rate: “It’s impossible to find a family without at least two or three members sick with dengue.” He said that IV fluids remain one of the most pressing needs, though supplies have slightly improved.

“At Al-Nau, IV bags are available for 3,000 Sudanese pounds. Outside pharmacies sell them for 5,000, and in Omdurman Hospital they cost 4,000. There was a severe shortage for weeks, but on September 25, around 2,500 IV bags were delivered to Al-Nau.” Volunteer initiatives have also played a role, donating basic medicines like paracetamol and some IV solutions,

Still, Gabay stressed that accurate data is hard to obtain: “There are no precise statistics, because Al-Nau only treats critical cases. Once patients are stabilised, they are referred to health centres for follow-up.”

Poor environment, poor health

Gauging the level of illness in the capital is nearly impossible, says Ahmed Zuhair, a monitoring and evaluation officer from the Sudanese American Physician’s Association (SAPA). Infections continue to rise by the minute, Zuhair told Ayin, while the health ministry lacks the capacity to keep track of all the cases.

“Every hospital, health unit, or treatment centre in Khartoum receives 40–50 new cases daily and roughly 1,000 new cases across the state each day, most of which are suspected dengue fever or malaria,” Zuhair said. By contrast, cholera cases have begun to decline across Khartoum State, with only limited spread still visible in parts of South Omdurman.

According to Zuhair, the roots of the crisis are environmental. “The environment is completely unhealthy; mosquitoes, poor sanitation, and piles of uncollected waste, especially in Bahri and central Khartoum, create fertile ground for viruses. One epidemic ends only for another to begin. The only solution, he says, is to address the root causes: improve sanitation and medical access for the populace.

Access to treatment remains tenuous at best for most civilians in the capital, he added. “Even when medicines are technically available, they are unaffordable given the economic situation. People simply cannot buy IV fluids or malaria treatment. Prices are a huge obstacle, and shortages are just as serious.”

Then and now

Mohamed Abdallah, an engineer and volunteer with Khartoum ERRs, told Ayin that the Arkaweet Health Center managed to survive during the war thanks to volunteers who had been trained before the army entered the capital city. “At that time, we didn’t face major problems except for severe cases,” he said.

He added that the situation is now very different. “The centre has only one doctor, a general practitioner appointed by the Ministry of Health, and he cannot handle the huge number of patients. The centre serves Arkaweet, Al-Maamoura, Al-Azhari, Eid Hussein, Soba, Al-Salama, and Al-Jarif. The pressure is extremely high.” According to Abdallah, there are instances where patients simply leave the health facilities without receiving treatment due to a shortage of available staff. “Almost every household has at least one dengue patient, sometimes two or three. Mosquitoes spread the disease fast, especially with abandoned houses and stagnant water.”

He added that the shortages are severe. “We don’t have lab tests, fever reducers, IV fluids, paracetamol, or antibiotics. The centre operates at less than 30% capacity. Families need mosquito nets, one for each person.”

Abdallah believes the outbreak of disease is reaching unprecedented, critical levels. “If things continue like this, we will face a health disaster. Dengue will spread, then typhoid and other diseases,” Abdallah said. “We may even need to quarantine the entire state.”