Hopeful signs to end Blue Nile’s cholera curse

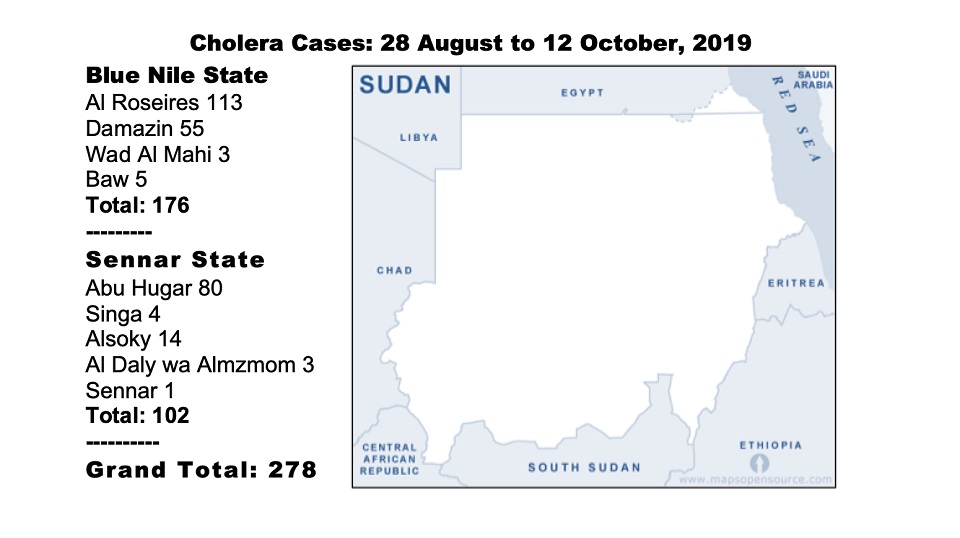

Today marks the end of the first phase of the World Health Organization’s cholera vaccine campaign in Sudan, first detected on 28 August in Blue Nile State. Over 1.6 million people were vaccinated in Blue Nile and Sennar states where 278 recorded cholera cases and eight deaths have been reported.

Sudan has experienced repeated surges in cholera outbreaks since 2016, WHO reports, with all of these cases originating from Blue Nile state. While the situation remains dire, the level of the outbreak is far more manageable than previous years, doctors told Ayin. Authorities are also more open about the situation than the past, the same sources said, which has assisted in their ability to react and treat patients.

“My kid was the first patient from this area to contract cholera and he passed away,” Habib Mahmoud, a retired policeman from Blue Nile State’s capital, Damazin, told Ayin. Habib’s child was actually his nephew but grew up with Habib since he was young. Mahmoud was terrified when his grandson, 11 years old, also caught the disease, potentially after visiting his sick relative days later. “Thankfully he recovered, he is even now back in school,” he said, adding that medical teams are now visiting homes providing the cholera vaccine.

Unfortunately, Habib’s story is not uncommon. Sudan has grappled with recurrent cholera cases where the first signs of the epidemic routinely start in Blue Nile State.

Why Blue Nile?

Bad environmental practices, large displaced populations residing in cramped conditions coupled with poor medical resources to contend with the disease are some of the factors contributing to Blue Nile State’s repeated cholera outbreaks, medical staff told Ayin.

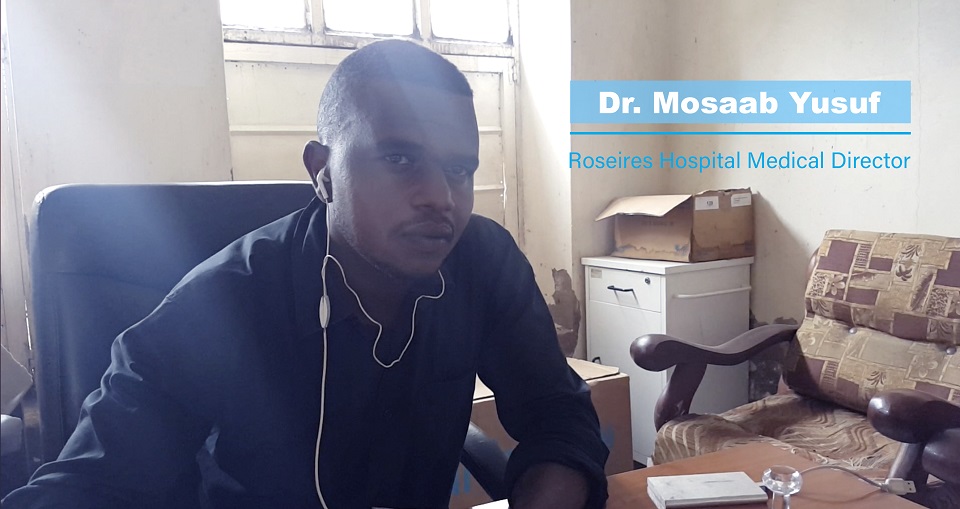

“Why is there always cholera in Blue Nile? In this state we have a poor environment, especially in places with high population density and little awareness of the disease,” said Roseires Hospital Medical Director Mosaab Yusuf. The medical director said one residential area in Blue Nile, Ganis, is routinely affected due to the cramped living conditions where the average house shelters 18 people, all using one latrine. According to Dr Mohaned Mohamed from the Central Doctor’s Committee in Khartoum, Blue Nile State’s poor infrastructure allows unsanitary material to enter the water supply that then spread easily across the state.

Many Blue Nile residents are displaced from the rebel-controlled areas, Yusuf adds, contributing to the congestion and exasperating an already under-resourced state health system. But the displaced do not only emanate from the conflict zones, says Dr Uhud Abdelaziz, who works in the Cholera Treatment Centre at Damazin Hospital. Authorities relocated residents after the construction of the Damazin Dam, Abdelaziz says, and relocated people to reside near the Nile. “Naturally, when the rainy season comes, all the waste from these residential areas drains into the Nile,” Dr Uhud Abdelaziz explains. Blue Nile State also relies on one dumping site that is based near the river, Dr Yusuf said, allowing rubbish to trickle in. “You have to remember people drink directly from the Nile,” he said, “and cholera spreads easily via water.” Both doctors believe cholera has repeatedly reached neighbouring Sennar State through the Nile.

Great Need, little resources

Despite the recurrence of cholera in Blue Nile, the state is poorly equipped to deal with the repeated crisis. The 2018 budget for health and education was 2.7 % combined. “The problem for health is the same as other problems in Sudan,” Damazin-based social activist Bakri Omer said, “the budget for health is too little in comparison to other areas.” The lack of health services, Omer told Ayin, “is why any disease in Sudan always turns pandemic.”

“This hospital needs a hospital to be a hospital,” says Dr. Uhud Abdelaziz jokingly. “We don’t have anything here to do our work easily,” she said. “When patients come, we are often forced to take them to another state hospital since we don’t have the facilities –this allows the disease to spread further.” According to Dr.

Mohaned Mohamed, they are facing severe shortages in pharmaceutical supplies and are unable to contend with major epidemics.Human resources are also in short supply. Incredibly, Dr. Mosaab Yusuf, the medical director for a major hospital in Blue Nile State, is not paid but carries out his work as a volunteer. “I have worked as a general doctor and now a medical director for Roseires Hospital as a volunteer all this time,” Yusuf said.

No reported cholera cases have emerged from the rebel-controlled areas of Blue Nile, according to the Sudan Relief and Rehabilitation Association [SRRA], but concerns are high. “The health situation is very fragile in our area,” says SRRA Humanitarian Officer Ishraga Khamis. “Flooding, a lot of movement in and out of the area and the lack of a referral system at Bunj Hospital make this area susceptible.”

Hopeful future

While still of great concern, the current cholera outbreak cannot compare with that of 2017, says Dr. Uhud Abdelaziz. “I would not even be able to sit down and do this interview with you now if it was 2017 – in those days we were constantly dealing with the crisis.” By June 2017, the Sudan government had reported over 4,000 cases and 12 cholera-related deaths in Blue Nile State alone.

But this time is different for many reasons. For one, unlike in 2017, authorities and the medical community are openly calling the epidemic what it is: cholera. In the past, Sudan authorities and its international partners would refrain from referring to the epidemic by its real name but refer to it as “acute watery diarrhoea”. “The spineless leadership of WHO continues to capitulate to Khartoum’s blind denials of the disease,” wrote Sudan political commentator and Lecturer, Professor Eric Reeves last year. “[These] denials reflect the regime’s not wishing the “stigma” of being a country with cholera.” But this time, Dr Abdelaziz said, authorities openly announced the existence of cholera. “Now we have all the information, from the very first patient diagnosed with it, the government announced that it was cholera and we were able to prepare.” The once state-censored media also reported on the epidemic so the public was aware, she added. Now patients are coming quickly to the hospital for treatment unlike in the past where scant information was available.

The new government’s openness to the cholera problem has also helped encourage both local and international non-governmental organisations to come to Blue Nile, Dr. Abdelaziz said. The entire Cholera Treatment Centre is funded and supported by the medical charity, Doctors Without Borders [MSF], she said. According to MSF’s head of mission in Sudan, Elmounzer Ag Jiddou, MSF has set up cholera treatment centres in Damazin and Roseires in Blue Nile State along with Sinja and Wad el-Nil in Sennar State as well as in Khartoum and Omdurman Hospital.

This more open approach to medical conditions may have led to more reporting on other epidemics affecting the country as well, Dr. Mohamed said. The Health Ministry announced a plan to contain vector-borne diseases including hemorrhagic fever in North Darfur and dengue fever in Kassala and North Darfur. This prompted people to start the social media hashtags “Kassala_is_dying” and “Save_Kassala” to draw attention to the situation.