Elusive peace, justice: Sudan’s path to peace maybe longer

Efforts to achieve peace with rebel factions and deliver former president Omar Al-Bashir for international justice appears less forthcoming than Sudan’s transitional government suggest.

Sovereign Council member and main peace negotiator, Mohamed Hassan Al-Taishi, was compelled to extend peace talks last week while significant stumbling blocks to achieve peace with the militarily active rebel groups remain. The peace talks are now meant to conclude by 6 March.

ICC: To see or not to see…

Just days before announcing a three-week extension to the peace talks with several rebel groups, Taishi announced that the government would be willing to present former President Omar al-Bashir and other suspects over to the International Criminal Court (ICC). “Our conviction as government, which made us agree to allow those who have been issued arrest warrants to be taken before the International Criminal Court, this decision, is based on the principle of justice, which is one of the themes of the revolution,” he said.

Taishi’s prior pledges to prepare Bashir and four others wanted for crimes against humanity to the International Criminal Court (ICC) appear to be designed to curry favour with the rebel groups than a genuine commitment to submit the suspects to The Hague.

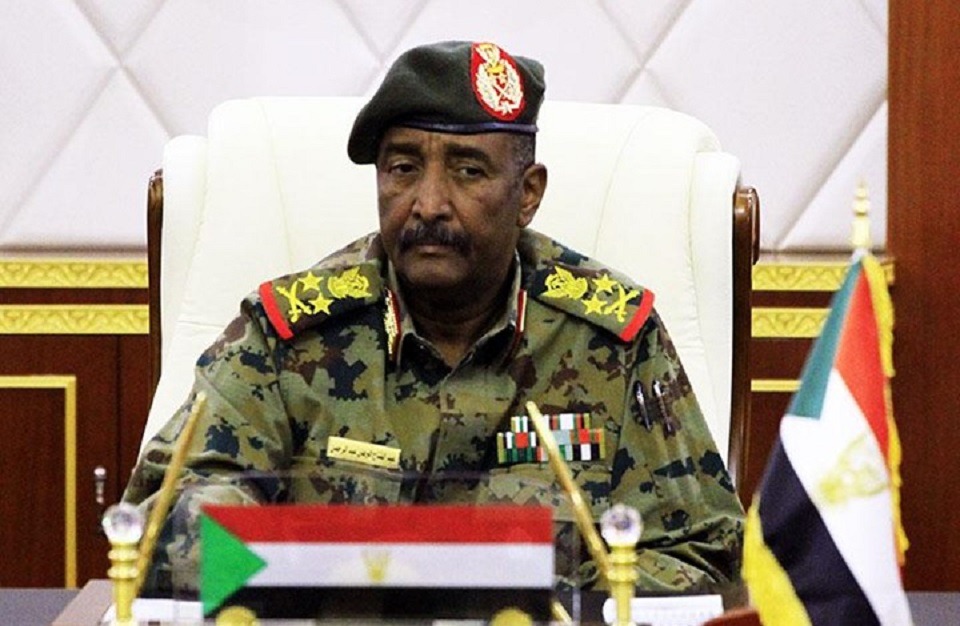

Almost immediately after Taishi’s announcement, Sovereign Council Chairman Abdelfattah el Burhan seemed to backtrack saying the appearance of Bashir and other suspected persons before the ICC does not necessarily mean they will stand trial at the court in The Hague. The Sovereign Council leader said the place for the trial and procedure was still up for negotiation.

“The government has plenty of latitude to wiggle out of this,” says Olivia Bueno, an independent consultant who has reported on the impact of the ICC in Africa for several years. “A lot depends on how much the rebels insist on this.” So far, the ICC has not received any official communication from the Sudan government to pursue the case, Bueno added.

Activists told Ayin Taishi’s ICC announcement was more a desire to show concrete progress in the peace process than a genuine commitment to delivering Bashir to The Hague. Pledges to hand Bashir over to the war crimes court have long been welcomed by the Darfur rebel groups, including the Sudan Liberation Movement under Abdel-Wahid that has not participated in the Juba-based peace talks.

Peace talks stagnate

While the largest militarily active rebel group, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North under Abdel Aziz al-Hilu (SPLM-N AH) have applauded the decision by the government to bring those accused of crimes against humanity in Darfur to justice, there is little to suggest it has helped in their peace negotiations.

“We are at a deadlock,” says Mohammed Jalal Hashim, Deputy Chief Negotiator for the SPLM-N, “One cannot even say that the negotiations between the two concerned parties have begun as the government delegation has arrested negotiations at the threshold, as the initial stages of the Declaration of Principles.” The SPLM-N has called for a secular state and the right to self-determination as foundations for the peace deliberations while the government delegation says secularism should be discussed as part of constitutional reforms, not peace talks.

According to Jalal, the people living in the SPLM-N AH areas of the Nuba Mountains have remained there despite hardships since they believe in freedom in religion and movement – elements the Sudanese state deprives them of. “People in the liberated area face bombs and shooting on a daily basis,” Jalal said, “People stay there since they believe in their liberation. SPLM-N gets its power from the people. If they lose people, then they lose themselves.”

Levels of distrust towards the military components within the government negotiating delegation are also a concern, Jalal told Ayin. “The transitional military council are playing games,” he said, “They put off [their] military uniforms and wear suits, sit in the backbenches while putting their civilian representatives in the front row, controlling the debate.” On 8 February, government officials demanded a formal apology from Jalal Hashim after public comments criticising the government delegation for bringing military and militia personnel to the peace talks. The government delegation temporarily suspended talks after Jalal criticised the Rapid Support Forces militia leader and deputy Sovereign Council head, Mohamed Hamdan Daglo (“Himmedti”), as “the one who kills cannot achieve peace.” The SPLM-N had temporarily suspended peace talks in October after the SPLM-N Secretary-General Amar Amun said 25 regular army and paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) attacked civilians in the rebel-controlled Khor Warral area of South Kordofan State.

Peace in the east?

While talks are stagnating in the south, promising signs of a peace deal in eastern Sudan are on the horizon –but these agreements may only work in Juba and not on the ground itself. Last Friday, the government and rebel Sudanese Revolutionary Front East track members signed a final peace agreement in Juba. The agreement includes provisions to ensure more political participation for people in Eastern Sudan and establishes a reconstruction fund, according to news reports. Just days earlier, however, hundreds of protestors in Port Sudan demonstrated against the peace talks citing a lack of inclusivity.

Jubilation in Juba, distrust at home

Similar reports of success with some of the Darfur rebel groups linked to the Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF) appear to receive little support from the public back home and question the overall validity of these Juba agreements.

“We have made remarkable progress in the negotiation process and we will continue discussions on the other issues,” said Darfur SRF negotiator Ahmed Tugud, expressing hopeful signs a peace agreement will be met within the current three-week extension period. Tugud’s optimistic stance came as the government and Darfur armed groups agreed to allocate a 20 per cent minimum of civil service positions to individuals from Sudan’s western region. While those in Juba cite this as a success, the multitude of conflict-displaced in Darfur feel under-represented and fear their demands will be ignored.

“The people who are appointed for the peace negotiations are often recommended from the cities, not from the IDP (internally displaced person) areas, but it is us, the IDPs, that are feeling the pain,” said Yahya Hasballah a resident of Atash Camp, South Darfur State. A chief and community leader in Atash Camp, Adam Ismail, not only believes the Juba peace talks fail to represent them but are also taking place at the wrong time. “The peace talks going on in Juba does not represent us as IDPs,” Ismail told Ayin. “And the time for the negotiations is not now since our main demand –that those who committed war crimes in Darfur are sent to court– has not occurred yet.” According to Ismail, they can only consider peace once their rights, including properties, are restored. “We lost everything from land grabbing. Right now we rent our own land (to farm) from the new tenants. This is our land.”

Eager for a conclusion

Whether supportive or critical of the outcome of these peace talks, many are eager for their conclusion to encourage key legal and political reforms. One of the key stipulations of the SRF at the inception of the Juba negotiations was to finalise the peace agreement prior to issuing appointments for state governors and legislators. While logical, this has seriously curbed any legislative reforms and allowed states to be controlled by members of Bashir’s former ruling National Congress Party.

As of last week, however, the South Sudanese mediation team in Juba announced that the appointment of governors and the legislative council would be discussed. Taishi told reporters in Juba that the necessity to achieve peace must go hand in hand with filling the administrative vacuum in Sudan’s states by appointing civilian governors. An encouraging sign for civilians across the country who have been repeatedly demanding the resignation of state governors affiliated with the past regime. Since the revolution began, civilians nationwide have organised at least 14 protests against National Congress Party state governors, calling for their removal and replacement, according to Sudanese Archive, an online open-source monitoring organisation.

The possibility of finalising the peace talks amongst the participating rebel groups before 6 March appears unlikely, especially for the SPLM-N, the only group with an active military presence in Sudan. Even in the regional tracks that do complete the process, many citizens within these regions may not accept their results. The net result of these delays and public complaints over-representation may play into the hands of the military, analysts told Ayin, by blocking key legal reforms and dissolving confidence in a civilian-led administration to achieve what has eluded Sudan for decades: comprehensive peace.