After El Fasher’s fall — Regional powers scramble to save Sudan’s army

14 November 2025

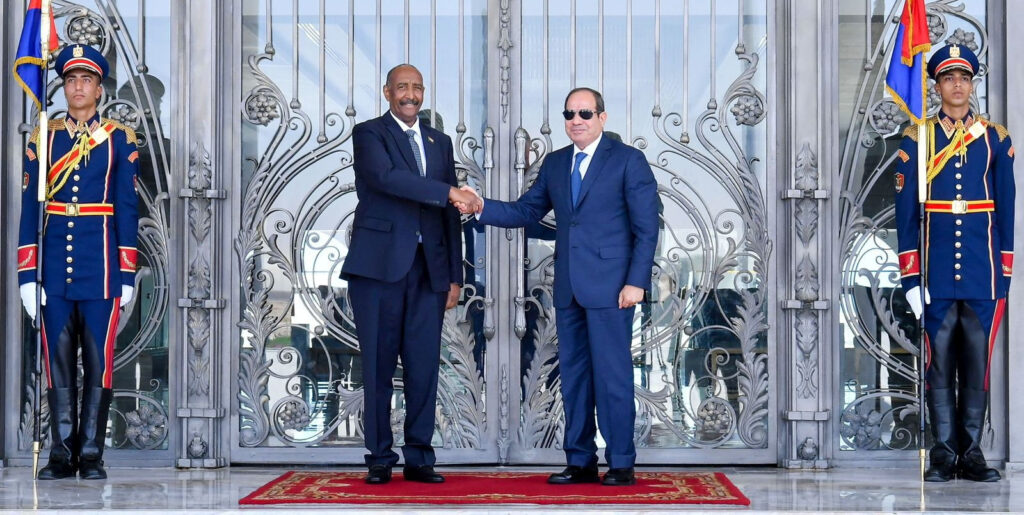

Diplomatic sources told Ayin that during a closed-door meeting in Geneva with U.S. envoy Massad Bolous, Sudan’s army chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan made a direct appeal for new military supply channels. The discussion, described by officials as tense yet pragmatic, focused on how the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) could reduce their reliance on Iran and Russia without losing ground to the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

According to the sources, Burhan requested an “alternative supply framework” to secure advanced weaponry and technical assistance from Western-aligned states. “His top priority,” the sources said, was to obtain early warning defence systems and air defence systems to shield key military installations and urban centres under SAF control from RSF drone attacks.

The urgency stems from RSF’s growing use of high-technology drones, allegedly supplied by the United Arab Emirates (UAE). These systems have inflicted significant damage on SAF positions across Sudan, exposing SAF’s limited air defence capabilities. Burhan, according to one diplomat, “was seeking any credible partner who could fill the gap — short of Iran and Russia.”

The Geneva meeting marked one of Burhan’s most overt diplomatic attempts to realign Sudan’s war strategy with Western and regional allies. Yet his request also exposed the growing complexity of Sudan’s foreign entanglements — where military needs, political legitimacy, and foreign influence collide.

Egypt’s calculated hesitation

Diplomatic sources said the envoy, Massad Bolous, later turned to Egypt—Sudan’s closest military ally—pressing Cairo to help equip the SAF with early warning and air defence systems. The move, officials believe, was aimed at preventing further RSF drone dominance and securing the skies over SAF-held territories.

But Egyptian military leaders have shown hesitation. While Cairo has provided political backing and limited logistical assistance to the SAF since the war began, its commitment to advance its air defence system remains uncertain. Egypt agreed to provide SAF with early warning systems.

According to diplomatic sources, Egypt’s reluctance is rooted in two key concerns: the financial and operational burden of deploying and maintaining such systems and the strategic risk of deeper involvement in Sudan’s war. “Providing air defence means a long-term military footprint,” one source told Ayin. “Cairo fears that would drag Egypt into a conflict it wants to control from the sidelines.”

Still, Egypt has quietly expanded its engagement. In the days following the fall of El Fasher—a strategic city in Darfur captured by the RSF—Egypt’s second-highest-ranking army officer travelled to Port Sudan for what insiders described as urgent consultations with Burhan. The visit, they said, was centred on revising the SAF’s military plans and exploring new tactical coordination.

The discussions reportedly included proposals for joint intelligence operations and technology transfers aimed at blistering SAF’s defensive capacity. While no formal agreement has been disclosed, the meetings signalled a renewed Egyptian willingness to prevent further SAF territorial losses— particularly in eastern and northern Sudan, where Cairo sees its interests directly at stake.

Turkey’s cautious support

Along with Egypt’s manoeuvres, Turkish intelligence and defence officials have also intensified contacts with their Sudanese counterparts. A senior Turkish official told Ayin that Ankara is prepared to expand both military and diplomatic support, though it remains unwilling to deploy troops on Sudanese soil.

“Sudan is not Syria or Libya for us,” the official said, underscoring Turkey’s desire to avoid another direct military entanglement. “But our support will increase — in the same model we use in Somalia, through training, equipment, and defence cooperation.”

This reference to Somalia is significant. In that country, Turkey established a model that combines arms deliveries, military training, and institutional support without direct intervention. Replicating such an approach in Sudan could allow Ankara to project influence without becoming militarily exposed.

Officials familiar with the ongoing discussions confirmed that both Turkey and Egypt are now coordinating formally to support the SAF and prevent further territorial collapse. Despite their historical rivalry, the two regional powers appear aligned on maintaining Sudan’s army as a counterweight to the RSF and the expanding influence of Iran and Russia.

“The fall of El Fasher served as a wake-up call,” one regional diplomat told Ayin. “Ankara and Cairo both realised that if the RSF continues advancing, the entire balance of power in the region will shift — not only in Sudan, but across the Red Sea corridor.”

Analysis: shifting alliances and new calculations

Diplomats interpret Burhan’s Geneva appeal as a clear signal of shifting allegiances. His willingness to distance the SAF from Iranian and Russian support marks a notable departure from recent months. This period included Iranian-made drones reportedly playing a key role in SAF’s limited air operations.

But Burhan’s move also reflects growing internal pressure. With the RSF continuing to advance in Darfur and Kordofan and the army losing critical infrastructure, senior commanders have been demanding more reliable foreign backing. The Geneva meeting, therefore, represented both a plea for help and an implicit admission of strategic vulnerability.

The pressure is also mounting on Egypt. Cairo directly links its national security and control over the Nile Basin to Sudan’s stability. However, the economic burden and domestic fatigue regarding foreign interventions have kept Egypt cautious.

Uncertain future

Despite diplomatic efforts, major obstacles remain. The cost of air defence systems, training personnel, and integrating technology into SAF’s fractured command structure are all major challenges. The SAF is also facing internal divisions, logistical constraints, and a decline in morale due to months of RSF advances.

For now, Burhan’s strategy appears to be focused on survival—securing enough foreign assistance to prevent further losses while signalling political flexibility to Western and regional partners. Whether that strategy succeeds depends largely on how far Egypt and Turkey are willing to go and whether the U.S. and its allies view Sudan’s military leadership as a reliable partner.

As one diplomat told Ayin, “Everyone is playing for time. Burhan wants to show he can pivot away from Iran, but without losing the war. Egypt and Turkey want to help him, but not to the point of owning the conflict.”

The coming months may determine whether Sudan’s military finds new lifelines or becomes further trapped between global rivalries. For now, the Geneva talks reveal more than a diplomatic exchange — they expose a deeper struggle over who will shape Sudan’s war and who will ultimately control its skies.