Sudan’s war on women

14 February 2024

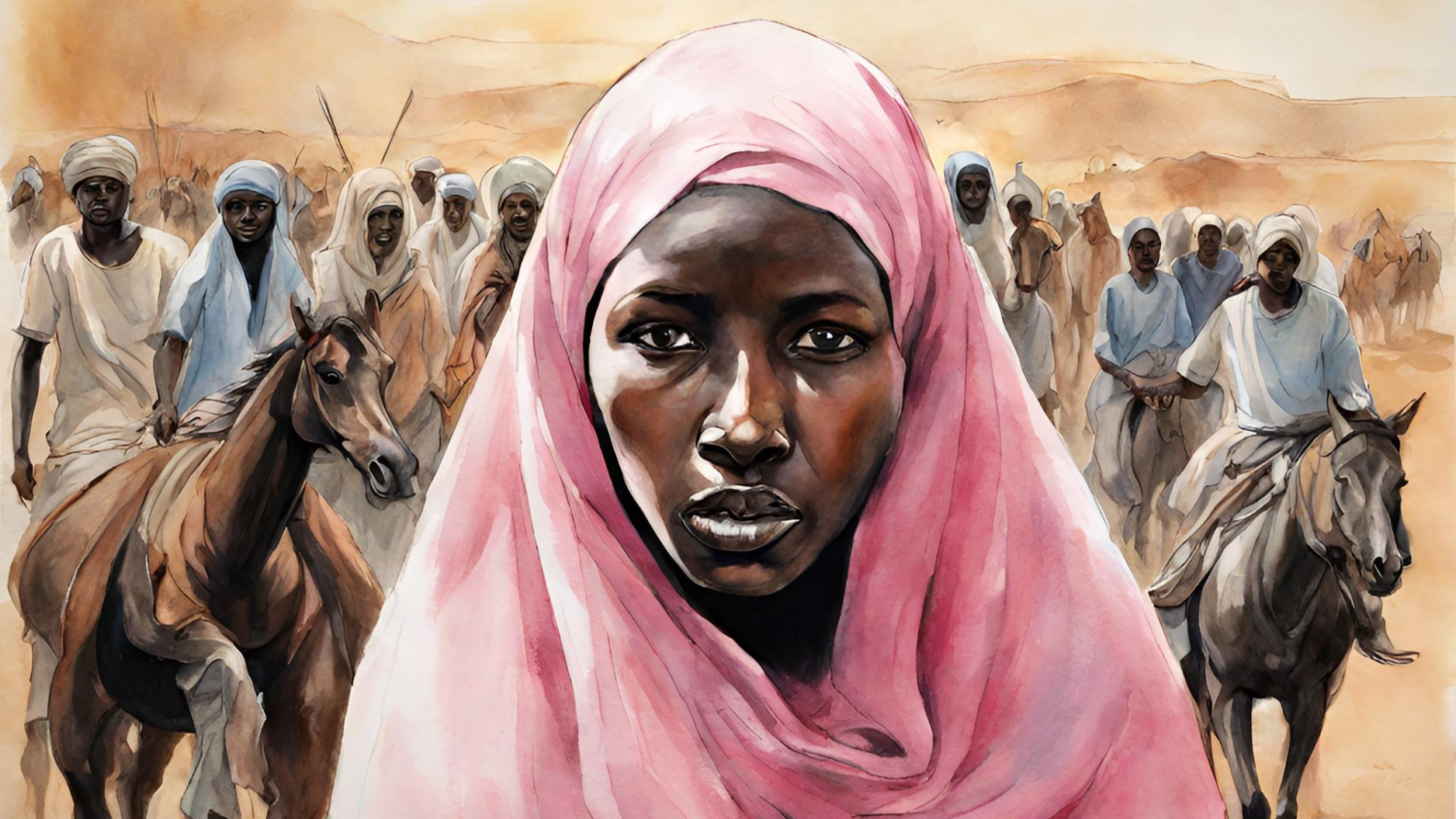

“They raped three of my sisters, they were beaten, and one of my sister’s hands was broken,” recalls Somia Musa after the Rapid Support Forces and allied militias raided Tawila, North Darfur State in June last year. While Somia managed to escape, her siblings were detained by the armed men for several days –only later did she learn they were in El Fasher Hospital, along with a dozen other girls. “Lots of our girls were raped,” Somia Musa told Ayin, “even abled-bodied elderly women were not safe from gang rape.”

Somia recalls the attack on Tawila well. The Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and allied militias flooded into the town with armored cars, motorcycles, and camels. Musa managed to flee Tawila with her children but hunger and thirst forced them to return to the town after the conflict, in hopes of taking supplies from their home. “They took everything from us, they left no livestock or anything, whatever they could not carry, they would burn.” It was during this attack that Somia saw armed men treat women as if they were commodities, literally spoils of war.

Testimonies of Sudanese women being raped, even kidnapped are prevalent, says Dr Salima Ishaq, the director of the state-run Violence Against Women and Children Unit. But Director Ishaq is the first to confess that their monitoring of these cases is only the tip of the iceberg to an expansive, ongoing problem.

Since the beginning of the conflict until November, the Unit has confirmed 136 cases of rape throughout Sudan, including 16 cases of minors, some as young as four years old. The Unit has also recorded 29 cases of women being kidnapped and held temporarily as sexual slaves, Dr Ishaq told Ayin. These recorded 136 cases “do not exceed 2%” of the total number, she added, since the Unit lacks access to many areas, while other women refrain from reporting these attacks, fearing the social stigma linked to sexual assault. This could mean the number of incidents is closer to 6,000 to 7,000.

Since mid-April, a war of political and economic dominance between Sudan’s army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces has taken place, displacing over 10 million people in the process. Sudanese women have been particularly targeted by both sides of the war, as multiple human rights workers claim the levels of sexual assault –even kidnappings of women– are reaching unprecedented levels.

Tawila: Escape from Kidnapping

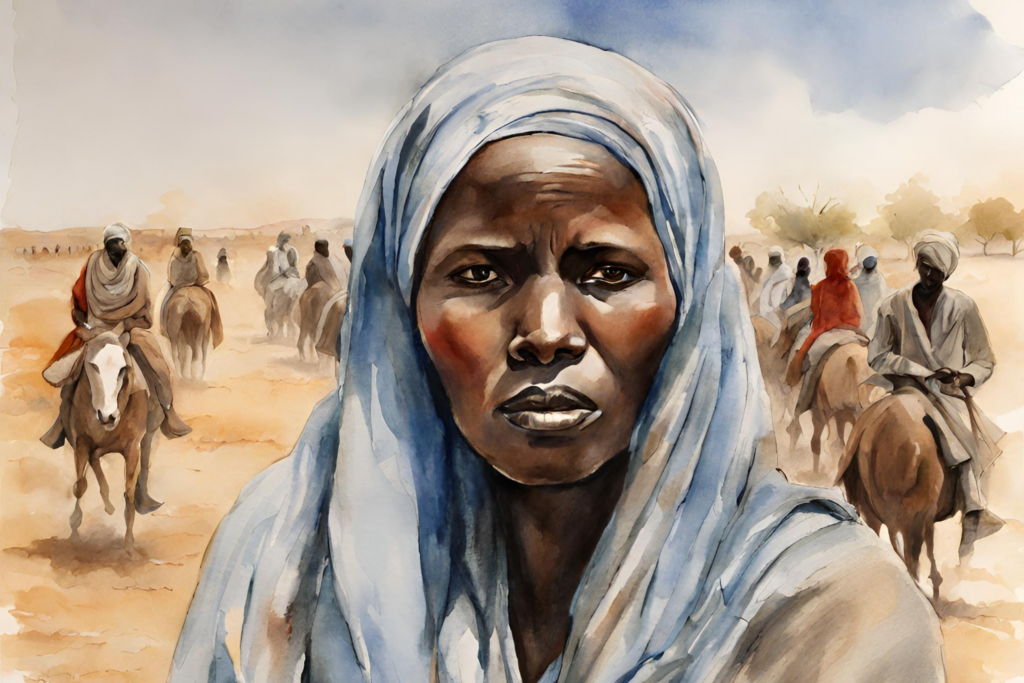

Fatima* can still recall those terrible weeks of uncertainty last June as she and her family attempted to flee the violence in Tawila, North Darfur after the RSF and allied militia raided the town. As Fatima tried to escape, one armed man, wearing the RSF uniform and carrying approximately seven magazines of ammunition, chased her on horseback. “We tried to get away from him, but he persisted,” Fatima said. She attempted to offer him her donkey and cart but the man “wanted me too, not just my belongings”.

The suspected RSF soldier kept Fatima detained for several days in a large RSF camp in North Darfur. He and his fellow gunmen threatened and beat her regularly. The man boasted of his riches –cars from Khartoum– and that he now “needed a woman”. According to Fatima, he said he would marry her, taking her to his family in Chad, and that he would kill any member of her family who tried to save her.

One evening, the man told her he was going to a meeting with the RSF camp leadership and ordered her to shower, change her clothes, and threatened to kill her if she tried to escape. Still bleeding from being beaten earlier, clothes torn, Fatima tried to escape but her assailants saw her so she hid under rocks and behind trees in the nearby mountain. “I spent two days in hiding, without food or water, barefoot and bleeding.” Fatima managed to escape on the third day while the RSF were sleeping, with several looted cars from Tawila around them and just kept running until she arrived in a remote agricultural area. Local farmers gave her water, and clothes, and treated her wounds. “My clothes were full of thorns, dry and stuck to my body, they had to pour water over me to take them off.” Fatima says she is still traumatised by the event and cannot go out into the public on her own. “Today I was asked to go to the farms, but I refused. I cannot leave the house.”

Another young woman from Tawila, only 15 years old, spoke to Ayin about her near capture by suspected RSF-aligned militia members. Hiba* had returned to Tawila town to collect some items after the fighting had subsided. “The moment I left the house, I found two men and a woman riding camels,” she said. The three asked her about her name and her father’s name –then they blindfolded her, tied her with a rope, put her on the back of a cart, and proceeded towards a mountainous area. When it grew dark and they prepared a fire, Hiba requested to be allowed to relieve herself. After they agreed to this, Hiba managed to escape and ran to the Zam-Zam Camp for the displaced. “I left my mother at the mountain and we got separated,” Hiba added, “I could not find my father here [Zam Zam Camp] and I’m still looking for him.”

West, Central Darfur

The targeting of women during the war, now approaching its tenth month, has taken place across Darfur, including the restive capital of West Darfur State, Geneina. Many women were sexually assaulted during attacks by the RSF and aligned militias in late April and June last year, according to Noura Mustafa, a social worker from Geneina who witnessed the violence firsthand. “Some of the victims were abducted from their homes and others were raped in front of their families,” Mustafa told Ayin. Men in RSF uniforms would enter each and every home, “some of them search for men, others search for weapons,” Mustafa said, “and there are those who look for virgin girls.”

Mona* was unable to leave her home in late April last year in Geneina when the RSF attacked. Armed men in large numbers surrounded her neighbourhood. “Three men assaulted me. One of them hit me on sight,” Mona told Ayin. “The three gang-raped me one after another at gunpoint.” In other cases, especially among those already displaced living in open shelters, Mustafa said, armed men would abduct girls from the streets, in front of their families. “In some cases, people suffered on the streets more than in their homes, it was particularly tough in Geneina.”

The African Center for Justice and Peace Studies documented 51 cases of sexual violence in Zalingei and Garsila, Central Darfur State, since the outbreak of conflict. The report claims the perpetrators were wearing the RSF uniforms.

Khartoum

Cases of armed groups sexually assaulting, even kidnapping women, are not only taking place in Darfur but other regions, including the capital, Khartoum.

One volunteer providing medical services at a major hospital in the capital told Ayin she had counted at least 31 cases of rape during the few months she worked there. The hospital is based in an area controlled by the RSF and this source only felt safe speaking to us with full anonymity. The volunteer says it can be challenging to know how to help survivors of sexual assault, especially since the facility lacks medical services. “One girl was raped and she is in a state of shock and does not know where she is or even her own name.”

While most of the cases of sexual violence were perpetrated by the warring parties, the volunteer said, some cases of rape have taken place at home, within families. As people take shelter from the war, trapped in their homes for long periods as heavy shelling takes place outside, women and girls are also at greater risk of domestic violence, according to a UN report. As well, young women are being forced into child marriages “as some families are allegedly resorting to it, in an attempt to “shield” them from further risks of sexual violence, assault or exploitation,” the report said.

Arwa Saber is a human rights lawyer and co-founder of the Survivors of the April 15th War initiative, an organisation that provides first aid help and mental support to survivors of assault.

Saber has, unfortunately, seen it all in Khartoum.

“The most painful tithing was the raping of children,” Saber told Ayin, adding that she has recorded several cases of young girls and, on occasion, boys as well. “There are also cases of women that were held captive by groups linked to the RSF and others to the army. Some were held for long periods, as long as two weeks, and were gang-raped constantly during detention.” In many cases, Saber said, the kidnapping and rape incidents involved women from minorities, “ethnicities which [the perpetrators] had issues with, or from the underprivileged area.”

From bad to worse

“What is happening in Sudan against women is beyond any imagination,” says Hala al-Karib, Regional Director of the Strategic Initiative for Women in the Horn of Africa (SIHA). “In fact, women [in Sudan] have been subjected to attack of sexual violence in the heart of conflict areas and the countryside during the past twenty years.”

Sexual violence against women has been a mainstay of all conflicts in Sudan –especially in the Darfur region in 2003 after Darfur rebel groups fought the army, along with state-supported militias –the precursors to the Rapid Support Forces. But al-Karib and other human rights activists concur that the levels of sexual violence are higher now than in the past and, as the conflict expands across the country, affecting wider Sudanese populations.

Since these cases of sexual violence take place with total impunity for the perpetrators, human rights activists in Sudan do not see this terrible trend changing. “There is a continuous silence regarding sexual violence crimes,” al-Karib added. “After the coup of October 2021, lots of sexual violence crimes were recorded. The crimes were intended and systematic –-70% of which were gang-rape incidents.” Unless cases of sexual violence are taken seriously and those responsible for these acts are held to account, al-Karib says, such cases will persist and continue to be institutionalised during wartime. “I hope that those who violated me get their punishment and that, in the future, laws will ensure accountability,” Mona told Ayin. “I know all three of them by name — they lived in my neighbourhood. I will never forget this. I will re-live this pain when I go back.”

* The name has been changed for security purposes