Trump-era team eyes power-sharing, resource pact in Sudan—but with major gaps

14 July 2025

A new U.S backed peace initiative for Sudan is quietly taking shape in Washington, according to multiple African diplomats and one Sudanese source with direct insight into US engagement in the country. The plan, reportedly driven by high-level Trump-era figures, is said to mirror the DRC-Rwanda model, with power-sharing and resource allocation framework at its core.

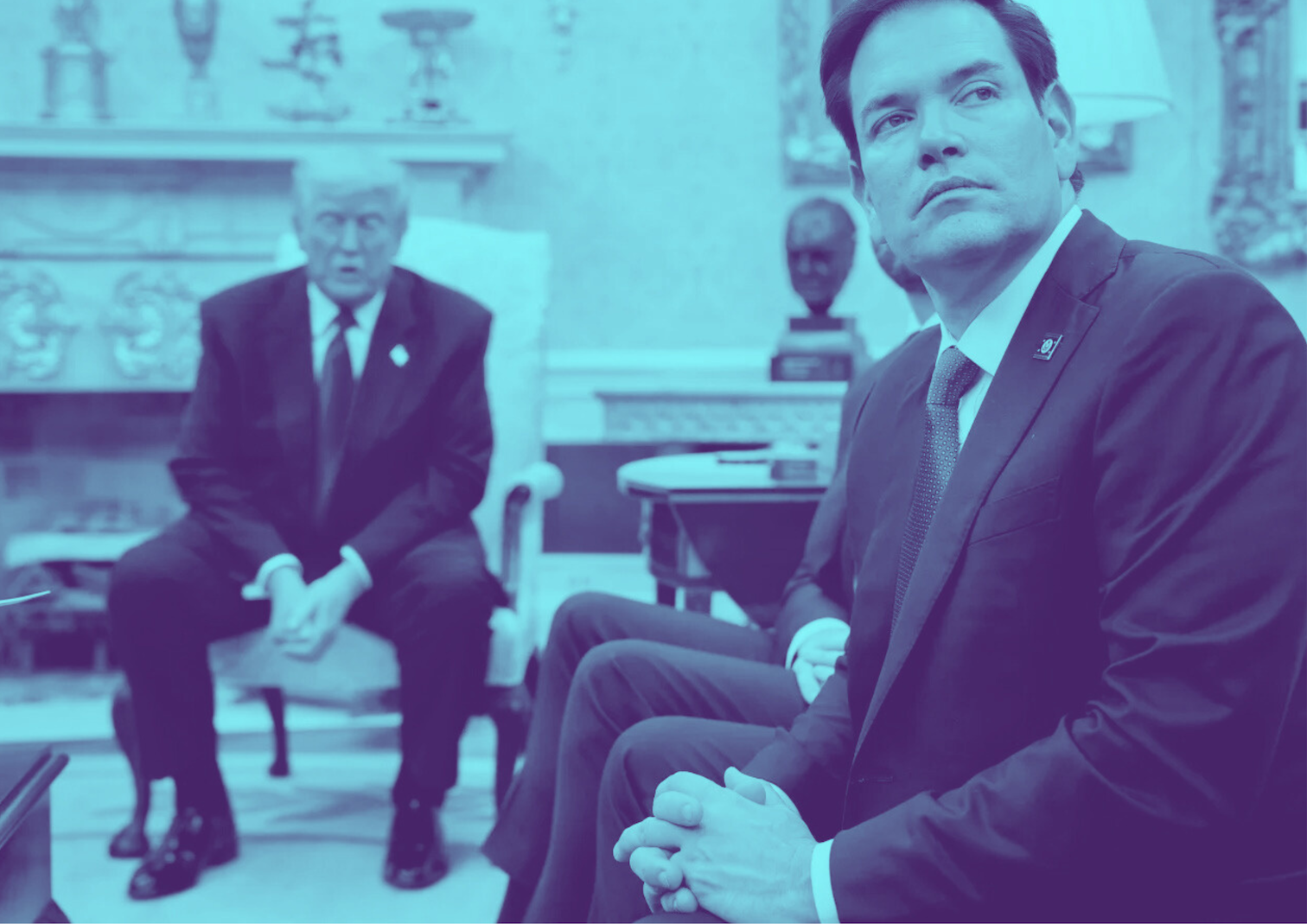

This initiative was confirmed a few weeks ago after Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced Sudan “would be next”, during the signing of the Washington agreement between the Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda. Rubio also corroborated this during a mini Africa Summit hosted by Trump. Multiple sources confirmed to Ayin that Rubio is expected to host a meeting on Sudan in Washington with the Foreign Ministers of Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE—signaling a continued focus on international actors despite his repeated assertions that the Sudanese conflict is an internal one.

The US plan is being guided by a group of senior Trump officials, including Chris Landau, Deputy Secretary of the State Department and members of the Africa and Middle East desks. Ambassadors from Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE in Washington, DC, have already been briefed.

A regional effort, not internal

While still in the early stages, the initiative has sparked concerns about its credibility, coordination, and potential to benefit external actors—particularly the United Arab Emirates (UAE)—more than Sudanese civilians devastated by the war.

The development comes as Sudan grapples with the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. Since the conflict erupted In April 2023 between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), more than 14 million people have been displaced and half the population face starvation.

Aid access is severely obstructed by both warring factions, and mediations efforts—whether led by the United States, the African Union (AU), or Saudi Arabia—have so far failed to yield sustainable progress. Amid this vacuum, insiders say a new track may be emerging, but with fundamental blind spots.

“This is different from Jeddah”—A Sudanese source speaks out

A Sudanese source familiar with US policy toward Sudan told Ayin that this initiative is a departure from previous efforts like the Jeddah talks facilitated under President Biden. “This is different from Jeddah—that was the Biden-Saudi setup. This is going to be in Trump style,” said the source. “It’s more like DRC and Rwanda, meaning a power-sharing deal and a resources deal as well—of which the UAE is likely to be the biggest benefactor.”

The source expressed skepticism about the institutional capacity of the US team currently pursuing the plan. “During the Biden administration, they had good working-level senior engagement but terrible higher-level senior engagement,” the source says. “But the Trump Administration has the opposite problem—good higher-level engagement from the Africa Special Envoy, members of the Middle East Special Envoy’s office and other State Department teams. But the issue is no working-level people. Some USAID and State Department staff are gone, fired, or their offices were closed.”

The absence of Sudan experts within the US administration raises doubts about the coherence of the strategy, especially when dealing with complex regional interests.

“I have no sense how they’re going to work on that—especially without Sudan experts sitting within the US government being involved,” the source said. “The issue for the Trump team is how are they going to deconflict the interest of Saudi Arabia and UAE on one hand, and Egypt and UAE on the other? These are all US allies.”

The source also noted a lack of clarity regarding Israel’s role in the process. “Israel has no problem engaging with Burhan for now because he signed the Abraham Accords. But he’s also aligned with Iran, while UAE is pushing for the RSF as a good alternative to the SAF,” the source added. “This could potentially turn terrible.”

Ayin reached out to the UAE Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the spokesperson of the SAF for comment, but no response was received by the time of publication.

Limited civilian input

While some contacts have reportedly been made with elite civilians—including former Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok, who is said to have spoken with US envoy Massad Boulos—there’s concern that the US team remains disconnected from the broader realities on the ground.

“They’re speaking to some civilians, but of course the elite civilians. I imagine the American team has absolutely no idea about anything else happening in Sudan,” the source concluded.

Babiker Faisal, a prominent member of Somoud, a coalition of civilian actors pushing for peace in Sudan, and Head of the Executive Bureau of the Unionist Alliance Party, fears the US initiative may prove too self-serving and provide few longterm solutions.

“We had previously stated that the protracted nature of the war and the lack of internal will to end the fighting would eventually lead to external intervention—one that would seek to end the war based on its own agenda, vision, and interests, which may not necessarily align with national interests,” Faisal wrote in a recent Facebook post.

“It is increasingly evident that President Donald Trump’s administration has embarked on a strategy to defuse international crises—including those in Africa—through what it terms “commercial diplomacy” which primarily aims to secure its economic interests, most notably access to rare minerals in its fierce race with China and Russia to control energy sources and artificial intelligence technologies.”

Diplomatic divide: African officials sound alarm

Multiple African diplomats who spoke to Ayin confirmed that something is brewing in Washington, but questioned the coherence, inclusivity, and regional coordination behind the effort.

One senior African diplomat dismissed any suggestion of regional involvement behind the emerging deal. “Our region is divided bitterly. So, they cannot guarantee or secure peace efforts, nor will they guarantee its implementation should it be inked.” The diplomat emphasised that unless Sudanese parties are committed to peace, external efforts are unlikely to succeed.

Another African diplomat said they had been informed of plans by the UN and the US to revive the so-called “Quartet” talks, but that clarity is lacking. “I learnt of the plan by the UN and US to revive the quartet,” the diplomat told Ayin. “However, the countries that will be involved in that meeting, when the time is earmarked, are UAE, KSA, and Egypt. I have never seen a mention of the AU and IGAD, but we look forward to their proposal.”

The diplomat noted that this upcoming meeting differs from earlier mediation frameworks and criticised the current focus on external players while Sudanese civil actors are largely sidelined. “Different actors have different initiatives –all aimed at silencing the guns and bringing the parties to the negotiation table,” the diplomat said. “As it is always with peace processes, agreements reached are implemented by a power-sharing government prior to transition into elected civilian government.” The diplomat declined to comment on whether resource interests are a factor in US engagement in Sudan.

Another African source familiar with the matter, speaking to Ayin on condition of anonymity, revealed that regional entities are aware that the U.S. and several Gulf states are among the key actors actively involved in mediation efforts aimed at ending the conflict in Sudan.

A country in collapse

Sudan’s war has plunged the country into a man-made catastrophe. Entire neighbourhoods have been emptied, and towns reduced to rubble. The RSF has been accused of ethnic cleansing in Darfur and atrocities across Sudan, while SAF airstrikes have indiscriminately hit civilian targets in Khartoum and Darfur. Humanitarian agencies warn that famine is imminent in large parts of the country, yet access remains tight by both sides.

In this context, the idea of a new peace deal model shaped behind closed doors in Washington, without broad Sudanese involvement, raises alarm bells. For millions of Sudanese trapped in a brutal conflict, there is no room for half-baked diplomacy. The stakes—lives, stability, and the future of the region—are simply too high.

“This deal smacks of nothing more than a band-aid being applied to a bleeding wound by those who just want to tick the boxes and issue the back-slapping statements,” said political analyst Dalia Abdelmoniem, questioning how any agreement could work without the involvement of civil society, political actors, and women groups.

“Are we expected to carry on like nothing has happened for the past two years?” she asked. “Will there be any accountability–any route to justice for the victims of this war?”