Sudan Conflict Monitor – 4 September 2023

The Sudan Conflict Monitor is a rapid response to the expanding war in Sudan written through a peace-building, human rights, and justice lens. Here we have tried to capture the five most important stories in Sudan. Please share it widely.

Powered by Ayin Media, Human Rights Hub, and the Sudan Transparency and Policy Tracker

Conflict updates: Al-Burhan toured SAF bases in Omdurman, Atbara and traveled to Egypt; Urban warfare has continued in Khartoum and Omdurman; Darfur and the Kordofans: violence takes on a life of its own. Violence in the peripheries is beginning to take dynamics of its own, apart from the agendas of the belligerents.

Humanitarian situation: allegations of misappropriation and mismanagement of resources.

Political developments: Agar’s roadmap. There have been reports about the diversion of humanitarian aid and attacks on health workers.

The Justice and Equality Movement’s Convulsions: A shake-up in the leadership of JEM is a signal of much deeper divides.

Instrumentalizing Justice Again: SAF claims that it will pass information on RSF crimes to the ICC, but will this advance accountability overall?

Updates on fighting

Al-Burhan Tours SAF Bases in Omdurman, Atbara, and Travels to Egypt

On Thursday, August 24, Lt.-Gen. Al-Burhan made surprise visits to SAF bases in Omdurman and Atbara, and traveled from there to Port Sudan. His sudden appearance triggered speculation about how he managed to break out of the five-month siege of the SAF’s headquarters. Burhan’s tour of the army bases gave SAF’s fighters a morale boost and offered him the satisfaction of appearing as a wartime commander adored by his soldiers.

Many questions remained unanswered, however, including whether his safe exit from the SAF headquarters was part of a deal with the US and Saudi facilitators of the Jeddah process, and therefore with the knowledge and cooperation of the RSF commanders. Many commentators favored this view. If this is the case, it is a sign of progress toward the signing of a monitored ceasefire agreement for at least three months, accompanied by the rolling out of a desperately needed humanitarian relief operation.

Others, however, argued that if Burhan was able to evade the siege without support, he might be intent on fighting it out. Burhan’s speech in Port Sudan on the 28th supports this view: he said he had no intention of concluding peace any time soon and pledged to fight “the traitors” to the last man or total victory. Burhan’s tone changed the next day when he met with the Egyptian President Abdel-Fatah al-Sisi in el-Alamein, saying “We are keen on putting an end to the war. “

Burhan also denied links of the SAF to Sudan’s Islamist Movement (SIM), unconvincingly contradicting mounting evidence implicating SIM’s jihadist fighters in spearheading the SAF’s ground offensives. The reemergence of militant Jihadists from the SIM and allied groups in neighboring countries in the ongoing war must have raised red flags not only in Egypt but also in the Arab Gulf countries and in intelligence community circles in Europe and the US.

Urban Warfare in Khartoum and Omdurman

In a major development, the RSF launched a large offensive against the sprawling SAF’s Armored Corps base in al-Shajarah, Khartoum South on August 20. RSF managed to breach the outer perimeter of the defenses of the base and tighten its weeks-long siege on several thousand SAF soldiers and volunteer fighters defending the base. The battle for the control of the Armored Corps is ongoing and will continue to cause heavy casualties among the belligerents and civilians in nearby neighborhoods.

The fall of the base to the RSF would represent a major setback for the SAF and threaten its hold on its remaining strongholds of the Engineers Corps and Wadi Sayedna air base in central and north Omdurman, respectively.

Prior to this, the parties had been fighting in Old Omdurman. Starting August 8, the belligerents turned densely populated residential areas there, such as Abu Roaf, Bait al-Mal, Wad al-Banna, and Wad Nubawi into a battleground. During the first few days of the clashes, their stray bullets and shells killed scores of civilians and sent hundreds to a nearby hospital, which launched desperate calls for blood donors, and later, gravediggers. The previous day, both the SAF and the RSF asked the population to leave “old Omdurman” as they mobilized for the battle. Since then, the old quarters of the historic city turned into ghost dwellings, with the few remaining residents roaming streets littered with dead bodies to give their neighbors ritual burials at great personal risk. A survivor recounted how a handicapped neighbor was left dead in his wheelchair for days before neighborhood volunteers gave his remains a decent burial in the courtyard of a health center.

The violent clashes in Old Omdurman were triggered by SAF’s 8 August offensive to retake control of the Shambat bridge, a key strategic asset for the RSF allowing it to link its forces in Khartoum North with those in Omdurman, and to resupply from the bustling the city’s large markets. This offensive represented one of the first instances of SAF ground troops engaging in a coordinated battle with combined aerial and field artillery support. However, the RSF repulsed the offensive and maintained its hold on the bridge, at great cost in lives and injuries for both sides and dozens of civilian casualties.

Darfur and the Kordofans: violence takes on a life of its own

Fighting interrupted months of relative calm in El-Fasher, the capital of North Darfur, on August 17, where some 51,000 forcibly displaced from Kutum, Tawila, and neighbouring villages found refuge after the war destroyed their areas in June. Clashes between RSF and aligned militias displaced tens of thousands of civilians from Kutum and Tawila, forcing many to find shelter in schools and other public buildings within El Fasher town, while others found space within camps.

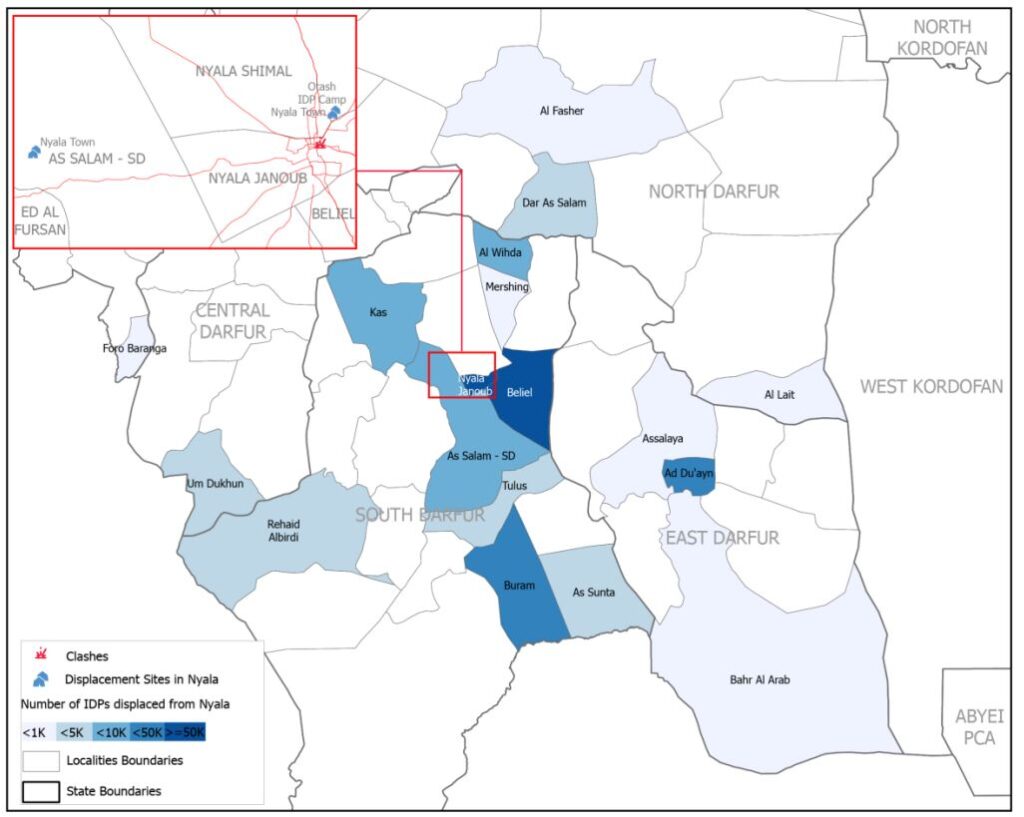

In Nyala, violence flared on August 14 and continued for days, after being intermittent for months. Shells fired by both sides are reportedly landing in residential areas. Five families perished among at least 39 people during artillery exchanges on 22 August between the warring parties. At least 50,000 were displaced following the resumption of SAF-RSF clashes in the city.

Residents in the southern neighbourhoods of Nyala appealed to both sides to allow civilians safe passage to move through the city and access the only fully functioning hospital in the city, Turkish Hospital. Access to foodstuffs and other essentials is increasingly limited with prohibitive costs few residents can afford. Most major markets are now closed, with the exception of the Geneina Parking Market which is protected by the armed forces, and the partially opened Central Market, based near the army command.

In South Darfur and West Kordofan states, two clashes illustrate how violence is taking on a life of its own, as described in a recent STPT opinion piece. Both instances were triggered by communities pushing back against looting that has evidently become a signature of RSF fighters. Both also involved fighters from communities that are considered solid constituencies of the RSF.

In South Darfur, scores were killed and injured the second week of August when tribal fighters from the Beni Halba people repulsed a looting spree by RSF fighters hailing from the Salamat people in the locality of Kubum, 100 kilometers south-west of Nyala.

In Al-Foula, capital of West Kordofan State, intense violence started on August 17, when police stopped and disarmed and later killed local RSF Misseiriya fighters returning from the battle in Khartoum with truckloads of stolen valuables. In response, the RSF joined the clansmen of those killed in attacking and overrunning the camp of the Central Reserve Police. For the next few days, violent chaos engulfed the city, playing on local resentment against the central government for its neglect of the oil-producing state. These historic grudges contributed to the ferocity of attacks on symbols of government authority in the town. Many government offices, including the Department of Public Records, the headquarters of the police and General Intelligence agencies, commercial banks, and local markets were looted and torched, as were offices and vehicles of relief agencies.

Local mediators managed, for now, to persuade all sides to stop the wave of self-destruction. A youth initiative urging the return of stolen goods set up a system whereby perpetrators could return items with no retribution. The effort met with some success as a number of items were returned to the main hospital and other state institutions, according to local sources within the city. The main hospital, however, remains closed and has forced the ill to travel for treatment to the neighbouring Babanusa.

The extension of the conflict to West Kordofan is particularly worrisome because of the risk of inter-ethnic clashes. The potential for clashes remains high between the Messeiriya and the Hamar, where the former has largely aligned with the RSF and the latter with the national army. Some sources believe the conflict in West Kordofan has been orchestrated by members of the former regime to instill conflict within the area that harbours considerable support towards the Rapid Support Forces. The conflict, the same sources say, will help prevent more RSF troops from entering Khartoum.

North Kordofan has also seen a return to fighting after a two to three-week lull, with RSF and SAF exchanging fire not only in El Obeid but also in surrounding areas. The RSF is deployed at the entrance of El Obeid and the national roads while the army is based near the general command in the city center, securing the airport and main market. Until recently, the relative stability within El Obied prompted authorities to return operations for banks, markets, and other institutions.

An open-ended strike carried out by doctors on 3 August, however, has led to hospitals working at half capacity with the absence of most basic treatment services. On 30 August, there was an attack on a Kuwaiti hospital in El Obeid in which RSF carted away recently received medical supplies, cash, and vehicles. In a counter-attack, serious shelling killed roughly two dozen civilians. RSF control over roads entering El Obeid has severely affected residents’ mobility –with multiple unlawful toll payments and blockades. Local dignitaries succeeded in persuading the RSF units around the city to allow safe passage to water supply technicians to ensure that the water reservoir that provides water to the city is properly maintained for the rainy season.

In South Kordofan, SPLM-N continued a blockade of the Kadugli-Dilling road, which worsened shortages.

The conflict, now in its fourth month, has exhausted the savings of local civilians, including many civil servants who have not received their salaries since the conflict started.

Perhaps one of the few silver linings to the current conflict is the revival of cultural events and various artistic activities taking place in areas outside of the capital. In August, the Kosti Cinema in White Nile State was re-opened, for instance, after being closed for 27 years. Fine art and theatrical performances are also being developed in Wad Medani, Gezira State, including the play “Barricades” which depicts the experiences of Sudanese living in displacement. The cultural and creative movement extends to the cities of Gedaref, Kassala, and Port Sudan, in the east of the country, which have recently witnessed extensive cultural and intellectual seminars, interspersed with implicit calls to stop the war in Sudan. Satirical and dark comedy sketches about, among others, the impact of the RSF occupation of private residences are abundant in social media channels.

Humanitarian situation

Allegations of misappropriation & mismanagement of relief supplies to Darfur

Amidst dire warnings that an estimated 20.3 million Sudanese, nearly half of the population, are facing war-induced severe acute hunger, insecurity, and widespread looting, misappropriation of relief supplies continued to hamper the flow of aid to those who need it most.

The most high-profile example of this was Darfur’s regional governor Minni Minawi repeatedly complaining that none of the relief supplies delivered to Port Sudan had reached the region to date. An anti-corruption activist revealed in an August 14 social media post how 13 trucks dispatched from Port Sudan with 350 tons of food rations went missing while en route for delivery to Darfur. By mid-August, 9 of the trucks, carrying 294 of the original 350 tons, were still stuck in the town of Kosti in central Sudan, exposed to the rain and the sun, risking their total loss. The post alleged the mismanagement and misappropriation of the funds released by the Ministry of Finance to the Ministry of Social Development, to pay for the transport of the relief supplies. Neither ministry either denied or countered issued a denial of these allegations, or gave its version of what happened.

Meanwhile, Hemeti’s office announced the establishment of the RSF’s own relief organization, the Sudan Agency for Relief and Humanitarian Operations (SARHO), on August 13. The organization is mandated to “enhance and coordinate relief and humanitarian operations” in areas under the RSF control. The well-crafted order reveals the RSF’s aspiration for recognition as a de facto authority that exercises control over large populations and swaths of land in Western Sudan and the national capital. However, much of the “the dire humanitarian circumstances and disasters that have arisen due to the ongoing war” cited in the order as a rationale for establishing SARHO are the direct result of the RSF’s widespread and systematic abuses, including ethnic cleansing campaigns and indiscriminate killings and other serious rights violations in Darfur and not the byproduct of SAF’s actions alone as the order claims.

Political Developments

Agar’s Roadmap

On 15 August, marking the beginning of the fifth month of the war in Sudan, the vice-chairman of the Sovereignty Council Malik Agar addressed the nation in a televised address saying that although there is no end in sight, the government had developed a roadmap to peace. The first phase, Agar said, would require the withdrawal of the RSF from urban areas and security arrangements to resolve their status. Humanitarian assistance for war victims would “come next”. The current circumstances call for the establishment of a “caretaker government” to focus next, inter alia, on jumpstarting the collapsed essential services and the payment of the salaries of public sector workers. It would also convene an all-inclusive political process to chart the country’s path to democracy.

Agar’s roadmap acquired new relevance following Burhan’s departure from the SAF’s besieged general command. It became evident that was not clear whether Agar’s blueprint represented the official policy of what stands for the “government of Sudan,” or his own recipe. The plan’s assertion that the conflict would only end “at the negotiation table” stands at odds with Agar’s boss and SAF commander Lt.-Gen. Al-Burhan’s promise to deliver a decisive victory over the RSF in an address to the nation was delivered the day before Agar’s.

Agar traced the root causes of the conflict to the mismanagement of Sudan’s diversity and a legacy of grand corruption under successive governments that peaked during the Islamist regime of deposed President Omer al-Bashir. In a blunt message to the Islamists and the NCP, he stated “No one has the right to question your patriotism but you ruled Sudan unilaterally for 30 years and no historian can overlook that South Sudan seceded on your watch. Don’t try to sell your expired goods here.” Sudan’s Islamist Movement (SIM) responded with a fiery statement, questioning Agar’s credentials, and asserting its commitment to fight alongside SAF in the battle for national dignity.

This episode offered another piece of evidence of SIM’s role in spearheading the social media calls for the war to continue and the accompanying campaign of recruitment of volunteers, SIM’s own fighting units, to join the SAF’s ranks.

In line with their now publicly acknowledged roles, SIM’s propagandists are unleashing daily barrages of ugly attacks on those calling for an end to the war, depicting them as traitors and RSF sympathizers. SIM’s political rivals in the Forces of Freedom Change-Central Committee are constantly in the crosshairs of the Islamists.

The Justice and Equality Movement’s Convulsions

JEM’s leaders are broadly seen as supporters of the breakaway Popular Congress Party (PCP) formed by Turabi following the split with the ruling National Congress Party (NCP). JEM is experiencing another split 23 years after its formation in 2000 when they first formed.

On August 14, Jibril Ibrahim, JEM’s chairman and senior commander and Minister of Finance, sacked four senior officials: Suliman Sandal, JEM’s official in charge of security arrangements, Ahmed Tugud, its chief negotiator, Adam Issa Hasabo, head of the Movement’s Kordofan chapter, and Mohamed Hussein Sharaf, deputy secretary for organization and administration. While the announcement mentioned no reason for the decision, sources said that leaders had unauthorised consultations with RSF. Days before his dismissal Sandal made an anti-war statement. Many saw it as a preemptive move to counter an eminent split by the four.

Tensions have been brewing for some time. In tweets on August 11, Sandal denounced the role of a “third party” covertly fueling the war by engineering its propaganda and mobilization campaigns by sending fighters to support the SAF in battles – a thinly veiled reference to the SIM and its Jihadist brigades.

At the same time, the JEM leader reportedly aided top SIM lieutenants, including several who broke out of jail, in their mobilization of recruits for the army in eastern Sudan.

Further, the four officials were accused of having secretly met with Abdelrahim Dagalo, the RSF’s second in command, in Chad in July. Jibril Adam Bilal, a London-based JEM political advisor, declared the sacking unjustified, and indicative of the chairman’s dictatorial tendencies. He presented those who were fired as neutral in the fight between the SAF and the RSF. His statement indicates that the opposition to Jibril’s leaders

Instrumentalizing Justice Again

In August, General Burhan announced a committee to document and carry out investigations into RSF’s abuses since the war started. This committee has since issued arrest warrants for dozens of RSF-affiliated people including Hemedti and his brother. SAF has also publicly stated they intend to cooperate with the ICC in handing over information about the RSF’s crimes.

The announcement shows that SAF is instrumentalizing justice by focusing only on abuses by RSF and not those committed by its own fighters, which like the RSF’s, include serious crimes that would fall under the ICC’s jurisdiction.

What might the implications of this action be? The SAF authorities, like any organization or individual, are entitled to send information to the prosecutor, but it is ultimately up to the prosecutor to decide which cases to pursue or not to pursue. At present, the ICC’s case on Sudan is limited to Darfur, but no longer limited to the atrocities committed 20 years ago. On July 13 the prosecutor announced that it would investigate ongoing crimes committed since the outbreak of war in April with a view to prosecution.

The RSF has committed heinous crimes not just in Darfur but in Khartoum and elsewhere in the country. If Sudanese officials are serious about involving the ICC in the pursuit of justice, the court’s jurisdiction could be accepted country-wide. This could be done by submitting a declaration accepting jurisdiction per Article 12 of the Rome Statute. In doing so, they would invite ICC jurisdiction in Khartoum.

But Sudan’s cooperation cannot be selective. They would be required – as al-Burhan and former Prime Minister Hamdok promised during Sudan’s short-lived transition — to offer full cooperation including handing over the ICC’s existing suspects: former president Omar al Bashir and former defense minister Abderaheem Mohamed Hussien, both reportedly in SAF custody, and Ahmed Haroun, last seen at large addressing NCP and Islamist movement cadres in Kassala.

Haroun and other ICC suspects from the former regime began a recruitment drive in eastern Sudan, intending to recruit 15,000 fighters in the three eastern states (Port Sudan, Kassala, and Gedaref). Local sources say the recruitment process is targeting specific ethnicities which could lead to future inter-tribal tensions in the eastern region. Lawyers and human rights activists have launched a campaign to have the ICC suspects arrested, inducing the suspects to leave Kassala.

More from our partner organizations:

Sign up for the Sudan Transparency and Policy Tracker newsletter here

• The Unthinkable Inferno is Yet to Come: Sudan’s Expanding War August 2023

• A Toxic Time Bomb: Messy Handling of Cyanide and Thiourea in Sudan August 2023

• Sanctions Hit Sudan’s War Chest, but More is Needed to End the Bloody Conflict July 2023

Follow Ayin: YouTube Facebook Twitter

• Sudan’s warring parties war against peace September 2023

• The Road to Adre: Sudan’s Most Dangerous Journey August 2023

• How mutual aid networks are powering Sudan’s humanitarian response August 2023