Sudan Conflict Monitor – 2 August 2023

The Sudan Conflict Monitor is a rapid response to the expanding war in Sudan written through a peace-building, human rights, and justice lens. Here we have tried to capture the five most important stories in Sudan. Please share it widely.

Powered by Ayin Media, Human Rights Hub, and the Sudan Transparency and Policy Tracker

- Spreading war Fighting is intensifying both in Khartoum and other key locations across the country.

- The Islamist influence Islamist leaders are conducting a recruitment campaign in eastern Sudan.

- Mounting atrocities, sexual violence, and attacks on activists Ongoing documentation efforts are showing targeting of civilians trying to flee and sexual violence.

- Obstruction of aid and targeting the health sector There have been reports about the diversion of humanitarian aid and attacks on health workers.

- International responses Competing efforts are making little progress and there is a need for more cooperation.

A 100 Days of War

August 2, 2023

July 23 marked 100 days of war between the SAF and the RSF, and the war shows no signs of relenting. On the contrary, it is intensifying and spreading. Reckless calls by the belligerents for the arming of civilians on their side are bound to deepen the already troubling ethnic polarization across Sudan and may widen out to the population as a whole, rather than being a conflict between two organized forces, if the international community doesn’t show more resolve in forcing the belligerents to step back from the brink.

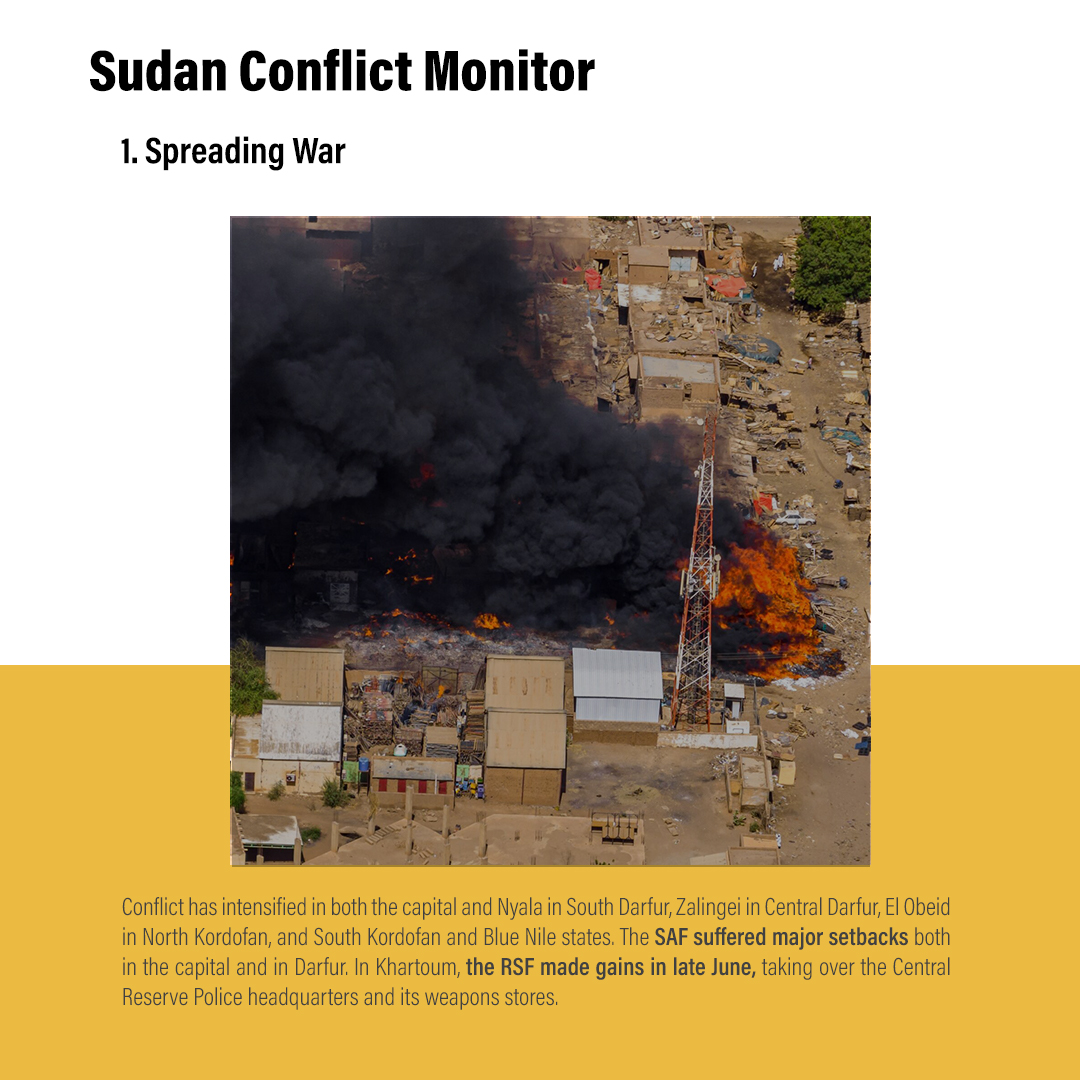

The conflict has intensified in both the capital and Nyala in South Darfur, Zalingei in Central Darfur, El Obeid in North Kordofan, and South Kordofan and Blue Nile states. The SAF suffered major setbacks both in the capital and in Darfur. In Khartoum, the RSF made gains in late June, taking over the Central Reserve Police headquarters and its weapons stores. In the first week of July, fighting in Omdurman intensified, with warring sides focusing on the Omdurman Radio and TV station held by the RSF since the outbreak of the war. The RSF continued to lay siege on the garrisons remaining in the SAF’s hands: the Engineers Corps and the Wadi Seydna Air Base and the surrounding military area of Kerari in Omdurman; the Armored Corps and the SAF headquarters in Khartoum; and the Signal Corps in Khartoum North.

On July 14, the RSF ambushed and destroyed a large SAF force of 120 vehicles, including technicals and supply trucks, which had been advancing south in two columns from a suburb of Khartoum North to break the siege of the Signal Corps and the SAF general command. The number of SAF soldiers and senior officers killed, wounded, and held prisoner created a shockwave in public opinion, with many expressing fears of an imminent collapse of army defenses. RSF’s position has also been bolstered by a video appearance by Hemedti in late July, countering rumors that he had been severely wounded.

SAF continued attacks on RSF positions on Eid El Adha despite initiating a unilateral ceasefire. Burhan called on youth and army retirees and reservists to join the army in his Eid address, indirectly acknowledging that the RSF outnumbered the SAF.

Beginning in late June, SAF intensified its air raids on concentrations of RSF forces near its besieged garrisons and on Halfaiya and Shambat bridges that allow the RSF to resupply from its rear bases in Darfur and North Kordofan. SAF aerial bombings and artillery from both belligerents have caused a rising number of civilian casualties and destruction of homes and commercial properties.

Rampant rights violations by RSF fighters, including the beating and unlawful detention of civilians and the occupation of private residences, continued unabated, despite a growing chorus of local and international condemnation.

Hemedti admitted in an Eid al Adha address that RSF troops had committed abuses and announced that he would set up a team to investigate reported looting incidents and apprehend and punish perpetrators. In response, an RSF Committee to Combat Negative Behavior later showed small numbers of private vehicles and other looted property allegedly recovered from unruly elements and looters and said they would be returned to owners.

The official death toll by the Federal Ministry of Health stands at 1,105, though a recent analysis by Reuters gathered from civilian Emergency Response Rooms and other civilian response networks showed that the tally was at least double the official count while acknowledging that this is probably still an undercount.

In Darfur, violence resurged in Nyala, the capital of South Darfur, where the RSF took control of the airport. Fighting in Nyala on July 21 and the following days caused dozens of civilian casualties in the city and reportedly forced 20,000 people to flee. The RSF also took control of the command of the SAF’s 61 Infantry Brigade in Kass in mid-July. RSF fighters and militias supporting them reportedly plundered the market and private residences, displacing thousands. Fighting has also spread to Zalingei and Central Darfur. Currently, out of Darfur’s five states, East Darfur is the only one experiencing relative calm, as it is the social base of the Rezeigat people from whom a majority of RSF fighters and commanders hail.

Ongoing fighting has taken a heavy toll on civilians with SAF-RSF artillery exchanges in the main cities of Darfur causing stray bullets and shells to randomly fall on people’s houses. Markets and property have been repeatedly looted in Nyala, Zalengei, and El-Fashir.

In Southern Kordofan, fighting between the army and RSF on June 22 was reported in Kadugli. The RSF had earlier attacked Debibat, another town in the state, and taken control of it. In the following days and weeks, a new front opened in the region as SPLM-N under Abdelaziz al-Hilu took control of at least 10 SAF bases, some south of Kadugli. Sources told us the movement acted because it had little confidence that the SAF garrisons in the Nuba Mountains were sufficiently equipped to repel RSF attacks. The movement thus appears to be seeking to create a buffer zone between its core stronghold in the Nuba Mountains and areas held by either the SAF or the RSF. The SPLM-N Al-Hilu is also said to be concerned about the RSF’s mobilization of its allied militias among the Hawazma and Misseriya people. These militias are being trained to fight in Khartoum and pose a security risk for civilians in the SPLM-N Al-Hilu-controlled areas. There is no evidence at this time of any military alliance or coordination between the SPLM-N and the RSF. On the contrary, the SPLM Al-Hilu moves are more likely intended to preempt RSF incursions into its areas.

In North Kordofan, fighting around the besieged capital of El-Obeid continued, with the airforce intervening periodically to scatter RSF concentrations around the city. The SAF declared the tarmacked road between the Omdurman and El-Obeid off limits to all traffic, claiming it was used to resupply the RSF troops and rations and to smuggle private cars solen from the capital. The SAF communique threatened noncompliant vehicles with bombing and said people should use an alternate route through Kosti which is controlled by its units. This vital road is also known as the “export road” for its crucial role in bringing agricultural products and livestock from Western Sudan to Khartoum and to export destinations. Its blockage has already raised complaints among livestock traders in Darfur and can add to economic difficulties.

In Blue Nile State, the SPLM-N al-Hilu attacked SAF positions concurrently with its progress in the Nuba Mountains, as UNITAMS confirmed. The government claimed victory in those confrontations. Malik Agar’s SPLM-N forces are now reportedly fighting alongside the army, following Agar’s appointment as deputy head of the sovereignty council. The Oumda Obeid Abou Shotal, a prominent local political and ethnic rival of Malik Agar, responded by donning the RSF uniform and becoming a voice of its war propaganda. Local authorities reportedly restricted movement in the region, ostensibly to prevent youth from joining the RSF. The rivalry between Shotal and Agar, respectively supported by Hemeti and Burhan, was a major driver of the widespread ethnic violence that struck Blue Nile State in July and October 2022, in which hundreds were killed, forcing the displacement of thousands.

A Reuters piece in late June on the influence of Islamists with SAF cited military and intelligence sources that said thousands of former regime Islamist militias were fighting alongside the SAF, generating controversy. Other converging reports alleged that prominent former regime officials, including Ahmed Haroun the former State Minister for Interior at the time of the launch of the genocidal campaign in Darfur in 2003, and Awad El-Jazz, who as Minister of Energy of the regime directed the oil revenue toward the consolidation of the regime’s security and political survival, visited Kassala and Gedaref states in eastern Sudan in mid-July to mobilize local militias to support the SAF war effort. Lawyers for the prosecution in the case against the two and other suspects for their role in toppling an elected government in 1989 reportedly complained about the failure of the two-state governments and police to apprehend jail escapees. Haroun is also a fugitive of the ICC, with an outstanding arrest warrant against him since 2007 for war crimes and crimes against humanity for his role in directing the 2003 campaign. It is feared that the SAF and Islamists’ recruitment campaign in eastern Sudan could trigger a flareup of the latent ethnic tensions in the region, triggering deadly ethnic confrontations as the region has repeatedly experienced.

As of late July, OCHA reported that more than three million were displaced by the war, with over 750,000 fleeing into neighboring countries. Of these, over 120,000 have fled violence in West Darfur to Chad to refugee camps near the border.

Aerial images released by the Humanitarian Research Lab show that large parts of El Geneina (.7km2) have been razed, and confirm the presence of corpses in the streets. Schools appear to have been systematically targeted. Tribal leaders in the region claim that over 10,000 have been killed, mostly from Masalit and other non-Arab populations outnumbered by the armed militia.

The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and Radio Dabanga reported that the RSF targeted civilians who attempted to flee the violence in Al Geneina. New arrivals in Chad told media and rights groups how RSF-backed militia groups attacked them, killing civilians, including children.

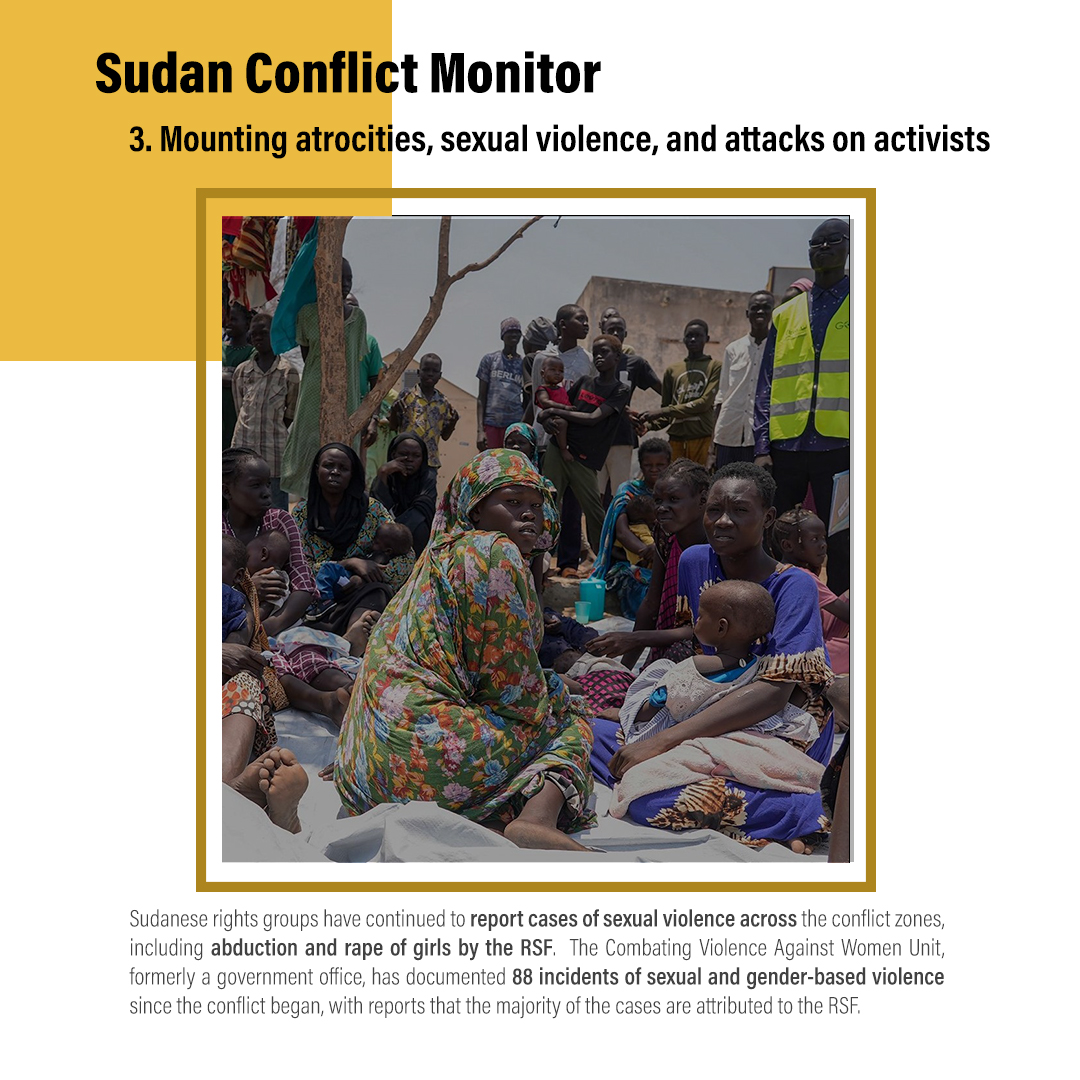

Sudanese rights groups have continued to report cases of sexual violence across the conflict zones, including abduction and rape of girls by the RSF. The Combating Violence Against Women Unit, formerly a government office, has documented 88 incidents of sexual and gender-based violence since the conflict began, with reports that the majority of the cases are attributed to the RSF.

Human rights defenders and journalists have also been targeted, with many shot, beaten, detained, and threatened by the two sides. Four Darfur Bar Association lawyers were killed after apparently being deliberately targeted, and the African Centre for Justice and Peace Studies reported on eight additional cases of threats against HRDs.

Diaspora-led, grassroots and international organizations have continued to sound alarms in response to the war, especially to West Darfur’s atrocities. The Darfur Bar Association has called for UN and AU monitoring across Darfur, especially in West and Central Darfur. On June 27, the Troika issued a statement calling for a coordinated international response and “condemned the widespread human rights violations, conflict-related sexual violence, and targeted ethnic violence in Darfur, mostly attributed to soldiers of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and allied militias.”

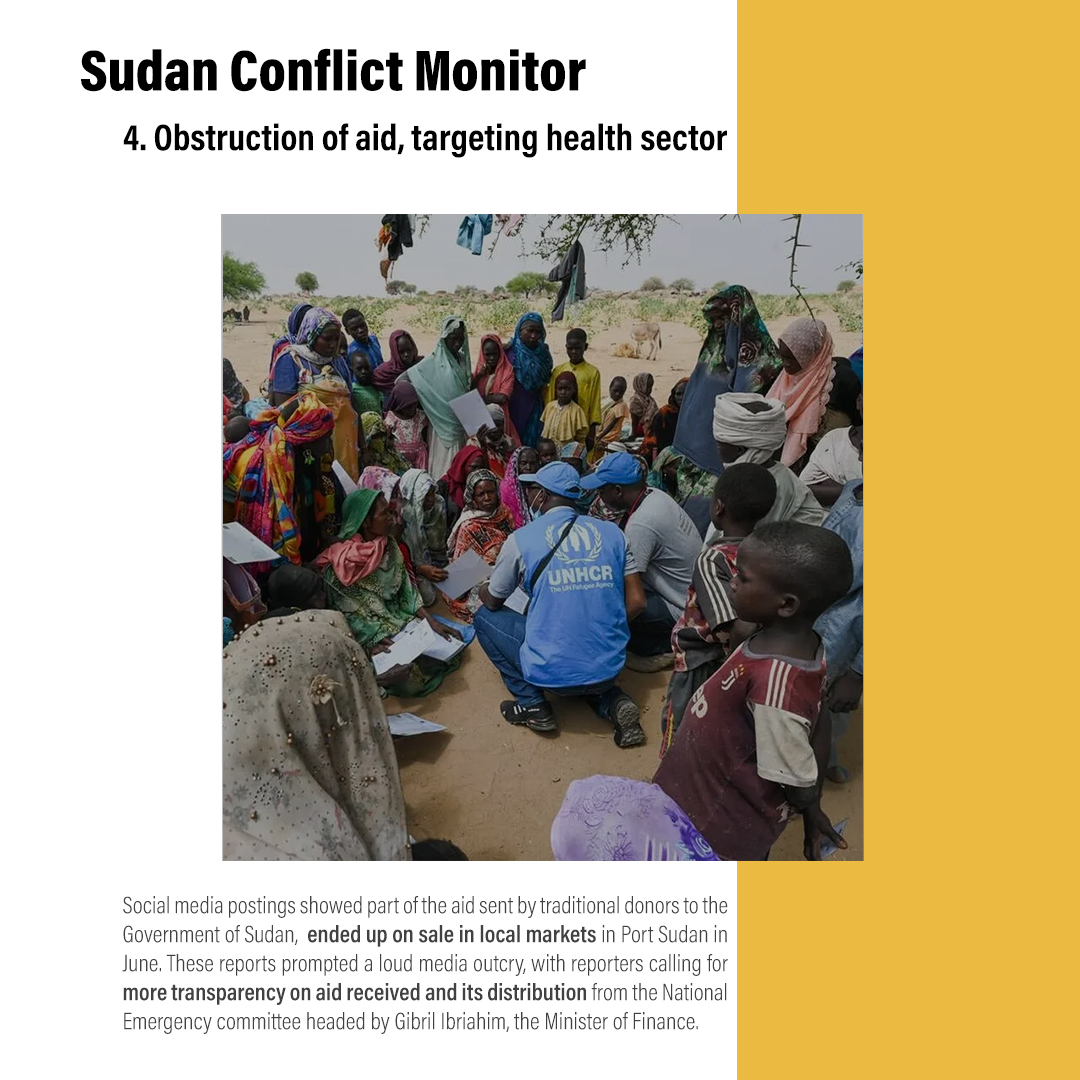

Warring parties have also obstructed and diverted aid. Social media postings showed part of the aid sent by traditional donors to the Government of Sudan, including Egypt, Turkey, and Arab Gulf Cooperation Council’s countries, ended up on sale in local markets in Port Sudan in June. These reports prompted a loud media outcry, with reporters calling for more transparency on aid received and its distribution from the National Emergency Committee headed by Gibril Ibrahim, the Minister of Finance. Around the same time, some 30 truck-loads of relief supplies were seized in Port Sudan as they headed to market. The UN has condemned the diversion of, and attacks, on aid several times since the war started in April, including the latest July 26 incident.

The ongoing violence has seriously undermined the country’s health infrastructure. The World Health Organization (WHO) now estimates that 80% of hospitals nationwide are no longer functioning. WHO has confirmed 51 cases of attacks on healthcare facilities and workers. Armed forces have occupied hospitals, targeted them with explosives, and looted medicines. At least 15 aid workers have been killed. WHO is warning that previously controlled diseases such as malaria, dengue, and acute watery diarrhea are increasing and likely to increase further as the rainy season begins unless urgent action is taken.

Several mediation processes emerged as leading in the regional and international efforts to end the crisis in Sudan: the Jeddah, IGAD, and Cairo processes, with the African Union adhering to a roadmap for resolving the crisis that defers to the IGAD lead in the matter. All platforms are pledging to cooperate, but multiple processes inherently encourage forum shopping and risk legitimizing the belligerents as the only interlocutors, as has happened before. More needs to be done to ensure that all mediation efforts are coherent and coordinated.

Jeddah Process: In early June, the US and Saudi Arabia suspended the ceasefire talks at Jeddah because, in the words of U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Molly Phee, “the format is not succeeding in the way that we want.” The US, however, left the door open to continued negotiations if parties showed renewed commitment. The SAF delegation returned to Jeddah in mid-June, indicating a renewed desire to negotiate, perhaps because their forces have fared poorly on the battlefield. According to sources, the Saudi-US facilitators of the Jeddah process have tabled a new proposal that requires the belligerents to agree to a prolonged humanitarian ceasefire of at least three months to allow the deployment of large humanitarian relief interventions. The plan also envisages convening political and civic actors in a parallel track of negotiations to end the conflict and outline the post-conflict political dispensation in Sudan.

The Jeddah process requires the belligerents to observe strict confidentiality and media blackout during the negotiation, this being the overriding norm of Saudi diplomacy. However, the silence around the talks collapsed in a flurry of statements from top officials of both parties. Sudan’s Acting Minister of Foreign Affairs stated on July 22 that the acceptance of the proposed truce would be conditional on the RSF evacuating public facilities and private homes and abstaining from looting. Lt.-Gen. Yasir El-Atta, SAF’s third in command, revealed other SAF conditions in a videotaped speech to soldiers in which he indicated that the RSF would be required to evacuate the capital and be cantoned in camps 50 kilometers away under international guarantees. After revealing that the parties achieved progress towards the establishment of a Joint Ceasefire Monitoring and Verification Team led by the Saudis, a July 26 SAF communiqué said its delegation to the talks was recalled to Sudan for consultations, pending the resolution of the sticking point of the RSF’s evacuation of public facilities and private residences. In response, an RSF spokesperson retorted that the SAF was seeking to achieve at the negotiations what its forces failed to do on the battlefield for Khartoum –the lifting of the siege around its remaining camps and the SAF high command.

The RSF appears eager to reach a ceasefire as well, but not at any price. The paramilitary force touts its control over much of the capital and the military advances against SAF in Darfur in its social media postings. However, despite its insistence that it is a defender of civilians in its public pronouncements, it eroded any possibility of public support d through the widespread atrocities it has committed. A prolonged conflict would continue to deplete the RSF’s political credibility and public support. This eroding support is likely to motivate the RSF to engage in negotiations, but it should be expected that the RSF will insist on collecting meaningful political dividends from its military dominance in the capital and Darfur in any negotiations, including the Jeddah talks.

The AU and IGAD: An AU Peace and Security Council held on May 27 in Nairobi “commended” and expressed support for the IGAD’s efforts to end the crisis in Sudan to IGAD. Chaired by Kenyan President William Ruto, the IGAD’s quartet of Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, and South Sudan ran into fierce opposition from the SAF, which accused Ruto of being biased towards the RSF. Although Ruto reportedly has business ties in Sudan, as revealed by a private trip to Sudan, IGAD affirmed its neutrality but said it could not be indifferent to the situation in Sudan, seeming to justify Ruto’s criticism of both belligerents and their shared responsibility for the suffering the war is inflicting on the Sudanese.

The SAF’s position risks blocking the IGAD’s role in the mediation even before it takes off as became evident on July 10 during the quartet meeting held in Addis Ababa. The quartet aimed to chart out its strategy for resolving the crisis and to engage with the delegates of the belligerents towards that end. Although present in Addis Ababa, Sudan’s delegation to the meeting declined to attend in a display of its disapproval of Ruto’s leadership, freeing space for an RSF representative to plead their cause. Observers from other platforms attended namely Saudi Arabia, the US, the UK, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates.

The quartet met in a special session with a delegation of the opposition Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC), highlighting IGAD’s commitment to enhancing civilian involvement in mediation processes. Although representatives of other vital independent civic actors from the trade union, resistance committees, civil society organizations, and women’s associations were absent from the meeting, the quartet’s initial meeting with the FFC, emphasizes the importance of autonomous civilian engagement in Sudanese processes, irrespective of the approval of SAF or RSF.

Cairo Process: On July 13, Egypt convened a meeting of Sudan’s neighbors in Cairo. Present were the heads of state and governments of the Central African Republic (CAR), Chad, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Libya, and South Sudan, the Chairperson of the AU Commission, and the Secretary-General of the League of Arab States. In terms of substance, the meeting’s communique was similar to that of the IGAD’s meeting in the same week, but the Cairo platform created a follow-up Ministerial Mechanism to explore approaches to resolving the crisis in consultation with the IGAD and other initiatives.

The initiatives’ specific responsibilities and focuses are becoming more evident. The Jeddah Process concentrates on the belligerents leveraging the combined weight of Saudi Arabia and the US, the Cairo Process aims to involve Sudan’s neighbors and preserve the Sudanese state, with the aim of preempting a collapse of the SAF and propping its role as central in Sudan, the IGAD Process focused on bringing the SAF and RSF top commanders to a face to face meeting as the quickest way to ensure an end to conflict, but the plan was derailed by SAF’s denial of cooperation with the quartet. The blockage appears to have also derailed the IGAD’s plans to lead in engaging civilians.

None of the three lead processes specifically focuses on the situation in Darfur. No solution to the crisis will hold without such dedicated attention to the serious mass atrocities the RSF continues to unleash in Darfur, without any meaningful action from the IGAD, the AU, or the UN, for that matter, to hold the RSF accountable.

A turn toward the Kremlin?

On June 29, the deputy head of the sovereign council, Malik Agar, visited Moscow in an effort to shore up Russian support. Russia’s foreign minister affirmed Russian support to end Sudan’s conflict. The move came days after the apparent coup attempt by the paramilitary Wagner Group, which is believed to have supported the RSF in Sudan, especially in gold mining operations. The consequences of the fissure between Wagner and the Kremlin remain to be seen. Agar also led Sudan’s delegation to the Russia-Africa Summit on July 27-28. The summit drew lukewarm support with only 17 Heads of State attending, less than half of those who attended the previous iteration of the summit in 2019.

Civilian initiatives to end the war

Sudanese civil actors inside and outside the country have called for an end to the war and worked to build consensus on the next steps. In mid-July, dozens of civil society resistance committees, civil society organizations, and women’s associations made their voices heard by endorsing a joint Declaration of Civic Actors to End the War and Restore Democracy. The Declaration calls for a ceasefire, monitoring, aid delivery, and a plan for Sudan’s political and economic recovery after the end of the conflict. Meanwhile, a “National Mechanism to Support Civilian Democratic Transition and Stop the War” held a virtual “Arkaweet Meeting” calling for an end to the war, security sector reform, border management, and institutional reforms. This Mechanism is focused on building consensus on establishing a civilian-led crisis government that would assume authority to manage the disasters triggered by the war and lay the ground for a mandated transitional government to take over once the situation stabilizes somewhat.

More from our partner organizations:

SUDAN TRANSPARENCY AND POLICY TRACKER

Sign up for the Sudan Transparency and Policy Tracker newsletter here

- Sudan Conflict Monitor, Issue #5 August 2023

AYIN NETWORK

Follow Ayin: Youtube Facebook Twitter

- Sudanese aid workers face hundreds of job losses 1 August 2023

- Mass graves discovered in West Darfur 21 July 2023

- Sudan army faces conflicts on multiple fronts in South Kordofan, humanitarian conditions worsen 17 July 2023

- Dar el Salaam, Omdurman: The worst indiscriminate bombing to date 12 July 2023