The fate of Russia’s Navy base: Repercussions inside and outside of Sudan

30 June 2021

Sudan has not refused Russia’s Navy base deal despite earlier signs in April. Allowing Russia full access to the Port Sudan base, however, may be problematic for Sudan’s government given the opposition by citizens and army officials alike, not least influential foreign actors such as the United States and Saudi Arabia.

Despite signs in April that Sudan had developed cold feet to the Bashir-era proposition to host a major Russian naval base off the coast of Port Sudan, high-ranking Sudanese officials recently claimed the deal may still take place.

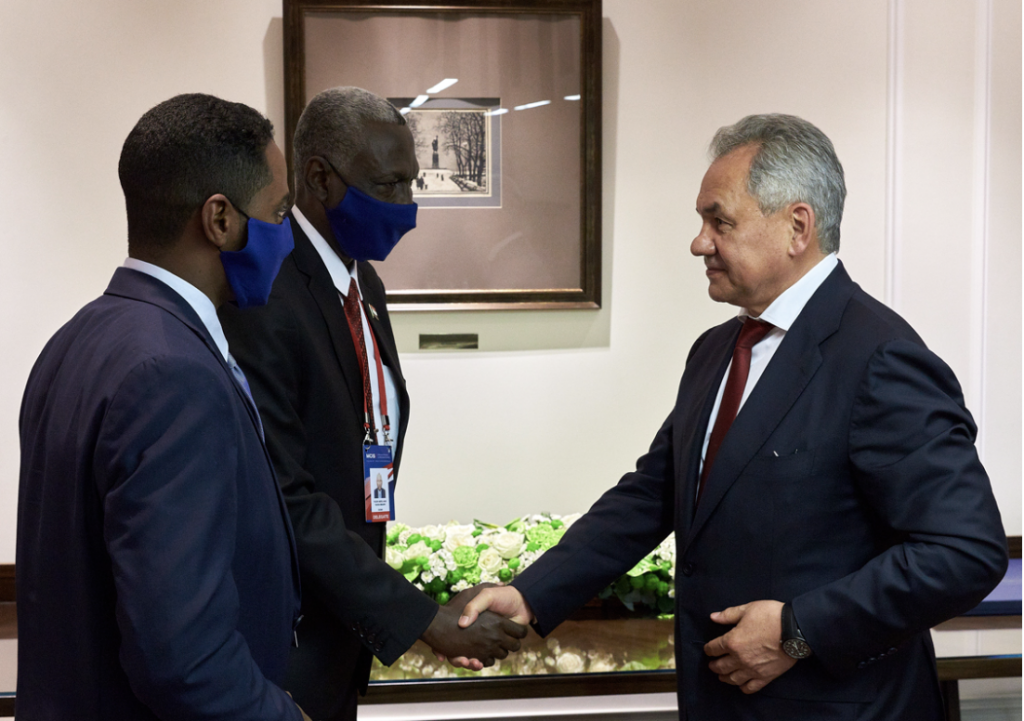

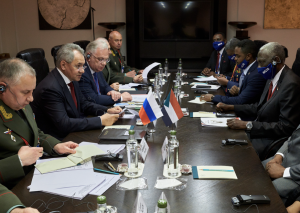

Last Friday, Russia and Sudan ratified an agreement to establish a logistics centre for the Russian Navy off Port Sudan’s coast. The logistics centre will assist Russia’s maritime forces for maintenance and refuelling but does not constitute a military base, a military source told Ayin. In an interview on Russia’s broadcaster, “Russia Today”, Sudan’s Defence Minister Yassin Ibrahim explained that they are in the process of reviewing several military agreements with Russia. Along with the approved logistics centre, the two countries are discussing the potential establishment of a Russian military representative to be based in Sudan as well as developing the Russian Navy base along the Red Sea coast. The latter agreements, however, remain on hold.

Earlier in June, a Russian military delegation led by Deputy Defence Minister Alexander Fomin held talks in Khartoum with the Sudanese Chief of Staff over setting up the base. “I think a compromise can always be found,” Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Mikhail Bogdanov said in news reports. “They have not denounced the agreement, have not withdrawn their signature, they said some questions have emerged,” he added. According to Chief of Staff, Lt.-Gen. Mohammed Osman Al Hussein during an interview on Blue Nile TV, Sudan is currently renegotiating the agreement to ensure it benefits the country.

News about the deal first surfaced late last year. The agreement reached during former president Omar al-Bashir’s reign allows Russia to set up a massive naval base in Port Sudan with up to 300 Russian soldiers and four navy ships –including nuclear-powered ones. Under the agreement, Russia has the right to transport via Sudan’s airports and ports “weapons and ammunition and equipment” where needed for the naval base to function. In exchange, Russia is to provide Sudan with weapons and military equipment. The agreement is to last for 25 years, with automatic extensions for 10-year periods if neither side objects to it.

“As for our country, we confirm our interest in strengthening partnership with Sudan in various areas, including military and military-technical cooperation,” said Russia’s Foreign Ministry Spokesperson, Maria Zakharova.

But the fear of upsetting some of the country’s major donors, namely, the United States and Saudi Arabia, led Sudan to postpone the deal in April and await the formation of the legislative council to debate the proposal, officials told Ayin. In May, Lt.-Gen Mohamed Osman Al-Hussein also said the agreement had a number of clauses included by the previous regime that could be considered harmful to the country.

From Russia with lots of artillery

Russia’s presence in Africa, in general, has steadily increased over the past few years with the country signing military cooperation agreements with at least 20 African countries. Many of these recent agreements utilize private military companies to function as Russia’s proxies on the continent. Providing combat, security and counter-insurgency services at a price, the footprints of infamous companies such as the Wagner Group can be seen in multiple countries –including Sudan. Run by Yevgeny Prigozhin, an oligarch with close ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin, the Wagner Group was first spotted in Sudan in December 2017, training Sudan’s armed forces and protecting Russian-owned gold mines.

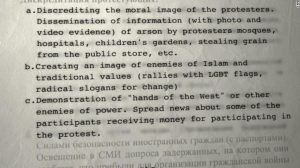

Prigozhin’s Wagner Group and another Russian company, M-Invest, assisted the former regime to suppress Sudan’s revolution by providing logistical services to Bashir’s security forces, including propaganda campaigns to stifle support for the revolution. “We saw them [Russian security forces] near the main streets where demonstrations took place during the revolution, monitoring protestors,” says Mohanad Ibrahim, an active participant in the sit-in that toppled former president Bashir in April 2019. “Russians were here in Khartoum as well as Nyala.”

Prior to the overthrow of Bashir in April 2019, there were as many as 500 Wagner contractors in Sudan. “Nobody wants to see Russia’s military-based here,” Ibrahim added, “they will only support [Sudan’s] military and suppress us.”

Jittery foreign allies

Sudan’s public may not be the only ones wary of Russia’s coastal presence. While no official statement has been made, the United States Navy’s presence in Sudan’s the Red Sea delivered a none-too-subtle message of US concerns over Russia’s military presence in the country. Just a day after the Russian warship Adrimal Grigorovich docked in Port Sudan in March, the US guided-missile destroyer USS Winston S. Churchill also arrived –the first visit by the country’s navy in over 25 years. “Together with Sudan’s civilian-led transitional government, we are striving to build a partnership between our two armed forces,” Rear Admiral Michael Baze said in a statement. US relations with Russia have remained frosty after reports of Russian cyber-attacks and election meddling –with the former issuing new sanctions against Russia earlier this year.

Saudi Arabia and Egypt also remain wary of an increased partnership with Russia, according to a diplomatic source within Sudan’s government who spoke to Ayin on the condition of anonymity. The source says both countries fear Russia’s ties to Iran and the latter’s support of the Houthi rebel movement in Yemen. In 2020, Saudi Arabia organised a security conference for the eight countries bordering the Red Sea to sign an agreement that prevents hosting military bases in the region.

The fate of Russia’s Navy base may also have geo-political ramifications with Sudan’s increasingly tense relations with Ethiopia over the disputed border region and water management of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. While tensions between the neighbouring countries ensue, Russia may be enforcing pressure on Sudan to comply with its Bashir-era plans to set up the Navy base by extending support to Ethiopia. In June, Ethiopia’s head of security, Temesgen Tiruneh held a meeting with the Russian Ambassador to Ethiopia, Yevgeny Terekhin on bilateral issues. Temesgen told the press after the meeting that Russia will support Ethiopia in developing its security services.

A chary army

Besides triggering international disputes among key foreign allies whose foreign aid is sorely needed, Sudan may face more volatile internal disputes between security forces over the final decision towards the Russian Navy base. The diplomatic official claims Russia may be indirectly supporting the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces [RSF] with weapons –strengthening themselves at the expense of the army. Russia identified the RSF as viable security partners after the Sudanese government failed to pursue kidnappers of two Russian pilots in Zalingei, Central Darfur State in 2015. After RSF forces under the deputy Sovereign Council head, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (“Himmedti”), managed to return the pilots, Moscow felt it has an ally in the western region. Since then, the RSF has played an integral role in supporting Russian operations with logistical and security support, the source added.

Nevertheless, the army finds itself in a quandary over the base. While some elements in the army may oppose Russia’s military influence, they are hard-pressed to refuse it. For decades, Sudan was dependent militarily on Russia because of harsh sanctions imposed by the United States against al-Bashir’s government. Moscow is considered the largest arms supplier to Khartoum and the Sudanese armed forces need Moscow to supply them with spare parts. Long-term, advanced military relations exist between the two countries in terms of armaments, training and information intelligence via satellite.

Facebook feuds

The debate over Russia’s Navy presence in Sudan appears to have extended to popular social media applications such as Facebook. On May 27, Facebook removed a whole slew of Russian propaganda supporting the country’s influence in Sudan –from inauthentic profile pages to groups designed to expand pro-Russian content, according to researcher Tessa Knight. The content primarily focused on promoting an image of Russia as a friend of the Sudanese people, while simultaneously painting prominent Sudanese leaders as pawns of the United States. The bulk of the content focused on promoting aid packages sent by Yevgeny Prigozhin and amplifying the benefits of the creation of the Russian Navy base in Port Sudan.

From 28 April – 3 May, several Facebook pages posted content relating to the benefits of the Naval base and accused “corrupt authorities” of putting a hold on its development. While at one point supportive of Sovereign Council head Lt-Gen. Abdel Fattah Abdelrahman al-Burhan, for instance, the social media posts turned face and started to criticise Burhan after postponing the Navy base deal.

The fact that the agreement over the logistics centre has been approved suggests a fully-fledged Russian navy base may be the next step for Sudan, no matter the domestic and foreign repercussions. Whether this will trigger further protests among a Sudanese public wary of Sudan’s military foreign partner’s expansion is another issue. “We cannot let them keep a base here, providing more weapons to the military,” Mohanad Ibrahim added. “Port Sudan will never allow it.”