No food for Ramadan – Corona’s deadly influence on food prices

Due to government measures in place to contain the coronavirus, Khartoum citizens only have a few morning hours to shop for food before the evening Ramadan futur (breakfast). But the limited time for shopping is the least of Hind Abubaker’s worries as she prepares for the sunset meal. “Prices have gone up and up,” Abubaker says, “this Ramadan we are hardly able to celebrate.”

Since the year began, prices for basic commodities have now doubled, and in some cases even tripled, according to local traders in the capital, Khartoum.

Bad then, worse now

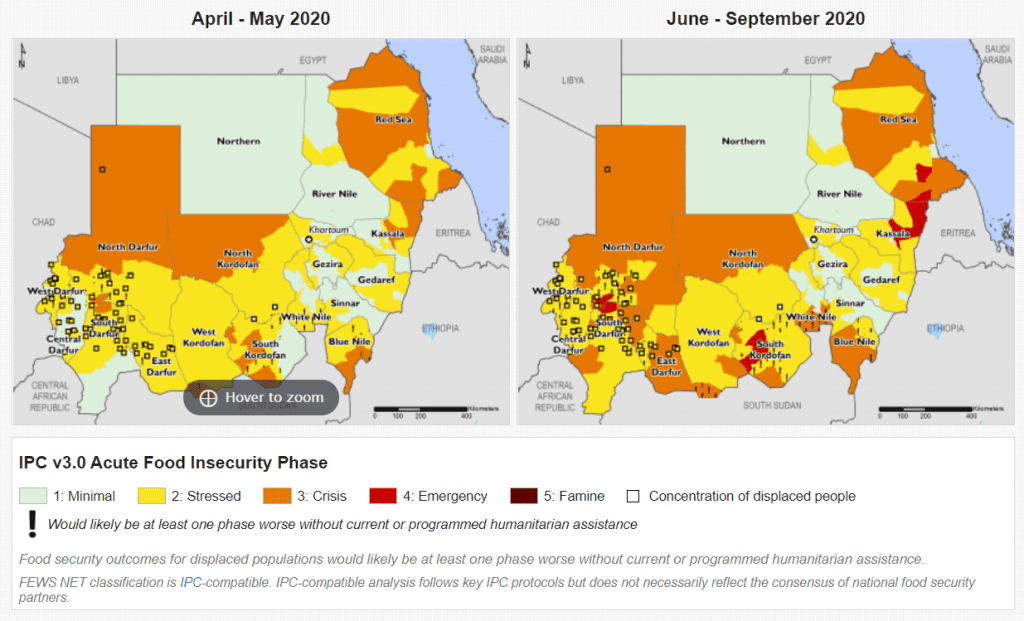

Even before Ramadan commenced last week, Abubaker says prices were prohibitively high. In February, the inflation rate was at 71% and food prices were double those cited in 2019, according to the US-funded food monitoring body, the Famine Early Warning System (FEWS).

Government measures to curb the spread of COVID-19 such as movement restrictions and border closures has impacted trade and contributed to further prices hikes. Local supply versus demand represents another factor. A cash-strapped government must import wheat at a time when major wheat exporting countries such as Russia are limiting exports to ensure there is enough domestic supply, the 2020 Crop and Food Supply Assessment Mission in Sudan reported. Wheat production in Sudan this year is estimated at 726,000 tons, the report says, representing only 25% of the country’s total consumption.

The cash-strapped government may also be losing a million dollars a day due to the virus, according to economist Bishara Al-Amin Mohamed. Blocked cross-border trade is severely impacting much-needed cash flows as well as curbed transport of goods within the country, he said. Livestock trade, for instance, is in decline and represents Sudan’s second leading export commodity. Export to Saudi Arabia, which consumes roughly 60% of Sudan’s livestock exports, is now halved.

Fasting during breakfast

Based on interviews with citizens across the country, Sudanese families appear more worried over lost income and rising commodity prices than infection from the coronavirus itself. The number of Khartoum residents facing food insecurity actually doubled since last year, according to the UN.

Ali Tarig from Singa town, Sennar State, says the measures to curb COVID-19 have led to huge price increases, especially fruits and vegetables generally eaten during the Ramadan holiday. With markets closed and heightened fuel costs, traders have increased prices, Tariq added. Given the economic conditions, few in Singa can adhere to the government’s social-distancing measures designed to halt the virus spreading. “People in Sennar have not accepted the decision to ban markets and the lockdown since they have limited incomes and do not have steady salaries,” Tarig said.

Corona in Sudan presents a vicious cycle – the virus will likely exacerbate food insecurity, a challenging situation that may very well allow the pandemic to spread further.

Hasham Ali, a builder and father of three living in the capital’s twin city Omdurman believes traders have used the virus as pretence to raise food prices. “Without money we are unable to eat and the prices are increasing daily,” Ali said, ”the government claimed they were to bring commodities, but where are they?”

Sudan’s trade and industry minister, Madani Abbas Madani, told Ayin his ministry launched a project last week in coordination with Sudan’s business union to provide basic commodities to the public with controlled, industrial prices. “The government cannot interfere in pricing goods since laws formerly used to do this were repealed in the nineties,” Minister Abbas explains, “the idea of the project is to fight price hikes and prevent brokers from any increases.” To ensure basic commodities are available during this difficult time the ministry has imported key commodities and restricted exports of vital foodstuffs such as maize, the minister added.

The government’s efforts to soften the blow against the economic consequences of a virus-lockdown may not be enough and there are few signs the international community will pick up the slack.

Sudan remains on the US State Sponsors of Terrorism list, denying them access to the International Monetary Fund-World Bank $50 billion trust fund to assist vulnerable countries to fight COVID-19. Sudan has issued one of the world’s highest aid appeals for 2020, requesting $1.3 billion but only 13% of this appeal is funded so far, according to Jan Egeland, the Secretary-General of the Norwegian Refugee Council. The Council was one of the 13 NGOs expelled from Darfur, Sudan by former president Omar al-Bashir in 2009 that are now invited back by the new administration, Egeland added.

Darfur

Some of those most affected by government measures to curb the virus come from the restive Darfur region. Prices are rising in an area where over a million people remain conflict displaced with few humanitarian organisations to assist them. After the pandemic came, according to local residents in South Darfur State, prices for basic commodities such as maize doubled while a kilo of sugar tripled.

Last month, health authorities announced two confirmed Coronavirus cases in Central and East Darfur States. Fathi Hussan is a resident of Al Daein, the capital of East Darfur State where one of the cases was reported. Hussan says the partial lockdown in place in Al Daein makes survival a daily challenge. “The basic question many people in the city ask is – if the government doesn’t provide me and my family basic commodities and yet it wants me to stay at home, from where do we get to eat?” Hussan believes Darfur residents are unable to follow the government’s directives as much as they may like to do so. “If you don’t provide people with basic commodities, people are unable to follow the lockdown measures – you see this happening all over the city.”

While towns in Darfur are wary of the virus spreading, Darfur residents agree that the internally displaced persons [IDPs] camps pose the greatest challenge in terms of containment. Blocked borders and restricted movements to curb COVID-19 has led to escalating food prices and limited aid access from humanitarian agencies. According to the World Food Programme, 15% of children suffer malnutrition in Central Darfur State and around 10% in West Darfur State. While over 80% of the malnutrition cases resulted from food shortages within the camps, according to the Humanitarian Aid Commissioner for West Darfur State, Mohamed Youssef.

Living in close proximity with limited access to health facilities, not to mention purchasing power for basic commodities, camp leaders are bracing themselves for another potential humanitarian disaster. A local camp leader for IDPs in Taweelah camp, North Darfur State, Musa Mukhtar, says it is very challenging to implement the correct virus prevention techniques. “Combatting Corona is difficult, even the process of washing hands is challenging given limited water access –not to mention medical sterilizers, masks and other protective devices,” Mukhtar said. According to the Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene, only about 23% of people in Sudan have access to soap and water.

Camp residents and local aid workers agree that the coronavirus will eventually spread within the IDP camps. Meanwhile, “hunger is already widespread,” says Ahmed Mater, an IDP residing in Geneina, capital of West Darfur State.