Mounting calls for justice: Kushayb’s trial and the ICC

With overwhelming support in Darfur for Kushayb’s trial commencing at the Hague, pressure is mounting for the Sudan government to bring other individuals accused of human rights crimes to justice. But a divided leadership, conflicting court appearances and a lack of communication between the ICC and Sudan authorities, may have stalled what millions of Sudanese have been calling for since the revolution began in December 2018: justice.

Adam Abdel was 13 years old when a former government-controlled militia under Omar al-Bashir killed his father by a firing squad. The ‘Janjaweed’ militia raided the town of Deleij, Central Darfur State, and arrested large numbers of people, including Adam’s parents. “By evening, they took them to the valley south of Deleij and he [Ali Kushayb] ordered their mass killing, there were about 147 – most of whom were notables and elders.”

Abdel is sure that the Janjaweed militia leader was Ali Muhammad Ali Abdalrahman, better known as “Ali Kushayb”, who ordered this attack along with 80 other attacks against towns around the countryside of Wadi Saleh. “He killed hundreds of dignitaries and leaders of the Fur.” Abdel says he saw Kushayb holding a small ax in his hand and directing his soldiers to burn villages in Central Darfur.

“Kushayb attacked all the towns located south and southeast of Central Darfur State, towns [such as] Makjar, Shatya and Kailik contain mass graves and were completely burned, women were raped and people were displaced to Kalma and Kass camps in South Darfur,” Abdel said.

On 9 June, Ali Kushayb surrendered to the International Criminal Court [ICC], Sudan’s Attorney General Taj Elsir al Hebir announced. Abdel was ecstatic upon hearing the news via his radio while sitting in Deleig, an Internally Displaced Persons [IDP] camp, Central Darfur State.

With overwhelming support in Darfur for Kushayb’s trial commencing at the Hague, pressure is mounting for the Sudan government to bring other individuals accused of human rights crimes to justice. But a divided leadership, conflicting court appearances and a lack of communication between the ICC and Sudan authorities, may have stalled what millions of Sudanese have been calling for since the revolution began in December 2018: justice.

Justice against past perpetrators of human rights was the central theme of civilian-led protests on 30 June where millions marched as well as the recent sit-in protests in Nertiti , Central Darfur State. Having seen slow developments domestically, many Darfur residents see the ICC and trials conducted in The Hague as the most viable option available.

“We are happy to prosecute Kushayb at the criminal court and we demand the Sudanese government to extradite the other wanted men who ordered Kuhsayb to carry out these massacres. The judiciary in Sudan is not impartial and controlled by the military, ”Abdel told Ayin . “The Sudanese judiciary, even after the fall of the Bashir regime, was unable to direct any charges against war criminals, so how can we possibly trust them?”

In 2007, the ICC issued arrest warrants against the former minister of humanitarian affairs, Ahmed Haroun, and the former militia leader, Ali Kushayb for numerous counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Issued in January 2018, Kushayb faced further charges for alleged massacres carried out in March 2004 in Deleij and surrounding areas. Three other individuals face ICC charges for war crimes and crimes against humanity in Sudan: former Defense Minister Abdulraheem Mohamed Hussein, former rebel leader of the Justice Equality Movement [JEM], Abdallah Banda Abakar, and the former president, Omar al Bashir.

“The day of the appearance of Kushayb at the ICC… it felt like we were celebrating Eid,” said Abdullah Khatar Abbas, a resident of the Abu Shouk IDP camp in North Darfur State. “We fully support the international criminal court and demand all suspects to be handed over to the ICC,” said another Abu Shouk resident, Mohamed Adam Hassan. “We hope Kushayb finds his penalty at the ICC, as IDPs, we were waiting for justice and accountability for 17 years.”

Upon Kushayb’s arrival to the ICC custody, ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda called on the Sudanese government to hand over the other four ICC suspects, including former president Omar al-Bashir. “In fact, by virtue of the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1593, the Government of Sudan has the obligation to cooperate fully with the ICC by surrendering those suspects to the Court,” ICC Spokesperson Fadi El Abdallah told Ayin .

Seemingly supportive

The Sudan government has repeatedly pledged its support and cooperation with the ICC. “As soon as Kushayb was handed over to the international criminal court, we issued a welcoming statement,” government spokesperson Faisal Mohamed Salih told Ayin. Mohammed Hassan al-Taishi from the ruling Sovereign Council and Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok—also confirmed the government’s commitment to cooperate with the ICC. Even the head of the Sovereign Council, Lieutenant-General Abel Fattah al-Burhan, told the international human rights watchdog, Human Rights Watch, “no one is above the law and that people will be brought to justice, be it in Sudan or outside Sudan, with the help of the ICC.”

But it has been over four months since these pledges of cooperation to the ICC and the Sudan government is yet to implement this commitment, according to Elise Keppler, the associate International Justice Director at Human Rights Watch. The ICC prosecutor told the UN Security Council on 10 June that the ICC had no formal contact with Sudanese authorities and appealed for dialogue with them.

But the government is saying the opposite.

“The reason the ICC suspects have not appeared to the [international] court yet is a lack of contact from the Court,” Salih said. “We expect contact and a visit by the ICC.” The spokesperson adds that they need to hold a detailed discussion to explore the option of holding the trials in The Hague or within Sudan.

ICC trials in Sudan

On 16 June, Attorney General Al Hebir reaffirmed their commitment to cooperating with the ICC but also indicated that it may prove a requisite to hold ICC proceedings within the country – a legal option open to the Court. Al Hebir mentioned in a June press conference that many legal obstacles existed before Sudan could hand over the remaining four ICC suspects to The Hague, including the need to amend laws and the outcome of the peace talks in Juba.

To hold the trials in Sudan would help retain an image of national sovereignty and provide a greater impact on the political level, says legal scholar Moneim Adam, who supports a hybrid court to try the ICC suspects as an alternative to The Hague. While nothing in the ICC’s Statute prevents it from holding trials in a foreign country, it has refused to do so in several cases, including in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Uganda and Libya.

Further, several legal reforms are needed in Sudan to make the domestic hearings feasible –and this may delay an already long awaited justice for Sudanese citizens.

For one, Sudanese law does not provide for someone to be held criminally liable on the basis of command responsibility. This is the legal principle that holds a superior responsible for crimes committed by his subordinates when they knew (or should have known) that the crimes were being committed. There are no provisions to protect and support witnesses and victims who may want to testify in an ICC case. And Sudanese law also includes sweeping immunities for members of the security services, protecting them from prosecution. All of these legal factors would prevent ICC trials –including a hybrid court system- from taking place in Sudan and would require months of law amendments to be fixed.

Complementarity

There is one factor that will certainly delay any state decision to deliver the suspects to The Hague: complementarity. The ICC follows the principal that any criminal prosecution-taking place –even if unconnected to international crimes- should take precedence to an ICC hearing, Adam said. Now that Bashir and other ICC suspects are facing trial for their suspected role in the 1989 coup, the ICC case will have to wait. “In this case the military coup is not one of the crimes that fall within the jurisdiction of the ICC, but it’s a legitimate case and has legal grounds,” Adam told Ayin.

Some within the security sector may currently be heaving a sigh of relief, knowing the results of the ICC trials could incriminate them. “The military that is now sharing power with civilians feel threatened when the word ‘justice’ is mentioned,” Adam said, “because they were part of the regime when the grave crimes were committed in Darfur and other parts of Sudan.” According to several civil society actors Ayin spoke to, there is a genuine fear within the security sector that Kushayb and other ICC suspects could implicate them via an international stage at The Hague. “People fear Kushayb is going to spill, it is not in their [the military] interests to cooperate with the ICC at all.”

While the ICC trials for Bashir and others may be delayed far into the future, the arrest and incarceration of Kushayb has influenced Sudanese authorities to hasten judicial reforms and possibly even trials. “I think this case will encourage the judiciary to speed up the process,” Salih told Ayin. “We are aware that there are problems facing the judiciary, including laws and systems that need reforms […] Kushayb’s case will push the judiciary to reform itself and improve capacity to try all criminals.”

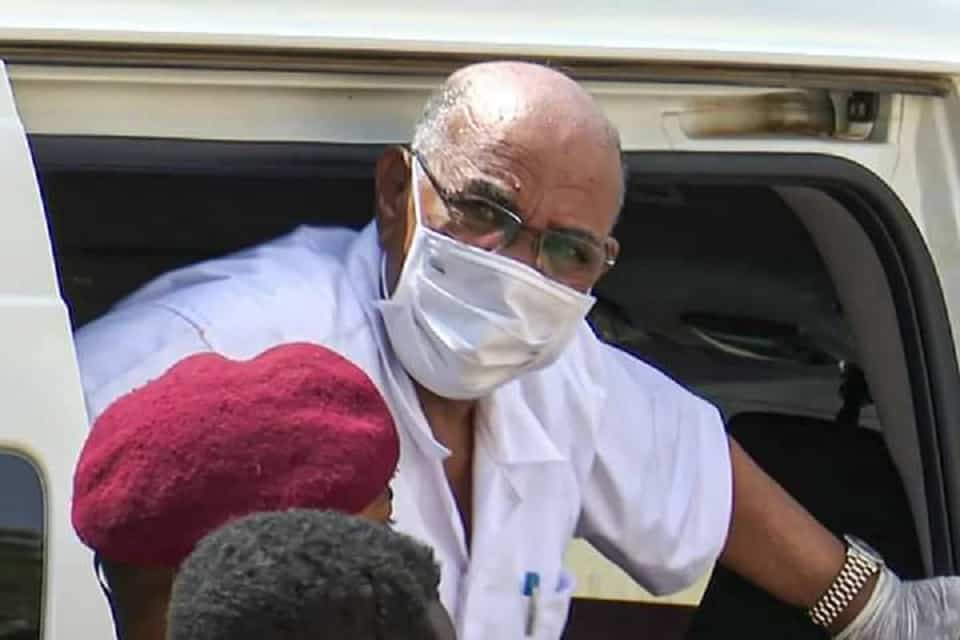

On Tuesday, ex-president Omar al-Bashir and a host of others linked to the former regime, including former vice president Ali Osman Taha and influential Islamist leader Nafie Ali Nafie, attended court for their role in the 1989 coup. Sudan’s former political elite appeared in a caged-off area in the courtroom amidst tight security situated in Khartoum’s suburbs. Bashir and his co-accused are charged under the Criminal Law for undermining the constitutional order and participation in a criminal act, according to prosecution lawyer Muawya Khidir. This is the second court case Bashir must attend, having already been convicted on corruption charges and currency irregularities in December 2019.

Asim Ibrahim, a resident of Nyala, South Darfur State, says he could not believe his eyes when the government news agency, SUNA, aired footage of Bashir and others from the former regime in court in Khartoum. “Of course, we who have been affected by Bashir’s wars are happy,” Ibrahim told Ayin , “but we are also cautious –we have yet to see justice emerge from a court in Sudan.”