The mass looting of Khartoum’s shops and markets

28 May 2022

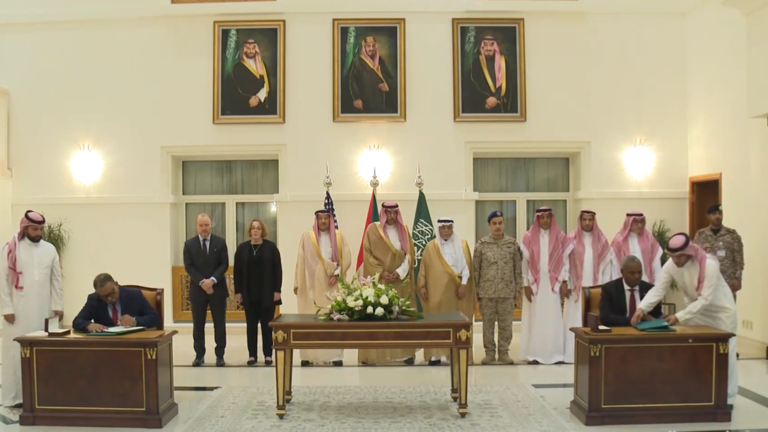

After the signing of the US-Saudi Arabia brokered ceasefire, merchants from the capital area are finally able to review their stocks amidst reports of mass looting since the conflict began nearly six weeks ago. Many merchants, however, were horrified to discover they have lost nearly everything they have worked hard to attain.

Youssif al-Tayeb, a trader from Omdurman market, did not expect to lose his entire stock, accumulated over 20 years, in a matter of days after his shop was looted during the conflict between Sudan’s army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces. Al-Tayeb’s store, previously full of foodstuffs, cash, and other belongings, is now completely empty, he told Ayin.

Youssif’s story is unfortunately echoed by nearly all merchants based in the capital.

Ever since a war of dominance between the army led by Lt-Gen Abdelfattah al-Burhan and his former deputy, paramilitary Rapid Support Forces leader, Lt-Gen Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (“Himmedti”), merchants have lost millions in looted stock. Within the first weeks of the conflict, Khartoum residents told Ayin, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) took control of major strategic areas of the capital while the army attempted to root them out through airstrikes. This has led, the same sources said, to RSF hunkering down within the city, looting stores, and embedding themselves within residential homes as temporary barracks and a means of survival.

According to Muawiya al-Hadi, a shop owner in Libya Market, west Omdurman, this market is being looted in broad daylight by armed groups, some of them wearing the RSF uniform and others in civilian clothes, using Land Cruisers and small “saloon” vans to carry their loot. “These groups targeted most of the stores in the Libyan market,” al-Hadi told Ayin, “as their members break the doors of the shops with bullets and target only the cash, and then leave the store open for criminals to loot the goods inside in a semi-systematic behavior.” Al-Hadi was forced to move all his stored goods to his home to protect his goods. Others, al-Hadi added, have decided to sit in front of their closed shops with firearms, in a bid to defend their property amidst the total absence of police.

Burning markets

The ongoing conflict has ravaged major markets such as Libya Market, once a mainstay for food shopping and imported clothes and shoes. Once bustling markets such as Al-Busta Market in Omdurman, Saad Qushra and Central Markets in Bahri, north Khartoum, and the Arab and French markets in central Khartoum are now empty and often burnt out of existence. The destruction of these markets, says economist Dr. Muhammad Al-Nayer, along with shopping malls such as Afra Mall and City Plaza, has resulted in billions of dollars in losses. “The extent of the destruction of these markets from looting is something completely alien to Sudanese people,” Dr. Al-Nayer told Ayin. “This war in the capital has resulted in huge financial losses that are difficult to quantify at the present time.”

In the midst of this financial loss, both warring parties have traded accusations regarding who is to blame for the looting of markets, banks, and citizens in residential neighbourhoods. The army has repeatedly accused the RSF of these acts while the latter repeatedly denies the charges, claiming criminal elements are to blame. A few days after the outbreak of fighting in mid-April, over 7,000 prisoners managed to leave their prisons in Khartoum. Here too, the army and RSF have exchanged accusations regarding the others’ involvement in the release of these prisoners, further exacerbating the security situation.

High levels of insecurity have led many merchants to move their remaining goods to their homes or, where possible, outside the capital altogether, leaving citizens with even fewer options for obtaining basic foodstuffs and other essentials, local residents told Ayin. According to economic analyst Ahmed Khalil, the looting and subsequent closure of markets in the capital have prevented civilians access to food supplies and ratcheted up the price given the lack of supplies and high demand. “It’s a catastrophic situation,” Khalil said, “many people no longer have any option but to wait for humanitarian aid that may or may not arrive from abroad.”

Brief respite

After a mediated week-long ceasefire was signed last weekend in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, Khartoum residents told Ayin they have experienced a relative respite from the shooting, except for limited cases. In a joint statement last Friday, the mediators of the ceasefire “noted improved respect for the agreement” but said there was nevertheless “isolated gunfire in Khartoum”. Few humanitarian aid agencies, however, have been able to access the capital area during this lull in fighting. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) was one of the few who did access Khartoum. On 25 May, the ICRC said they were able to begin distributing aid to seven hospitals in Khartoum. The looting of humanitarian aid has also hampered aid efforts. Just two weeks into the war, gunmen had looted roughly 4,000 tons of humanitarian aid from the World Food Programme (WFP).

Youssef al-Tayeb still does not know what he will do after discovering his shop had been completely ransacked, including the money he had saved to invest in his children’s education. “I feel very sad for the loss of my money [but] my personal loss is nothing compared to the extent of destruction that has befallen Sudan. We have lost an entire country – we have lost every reason to live in it.”