Famine by any other name: dire predictions for Sudan

30 July 2024

The 1984 famine in Ethiopia, where some estimate nearly 1 million deaths, was met with international outcry, culminating in Live Aid, a major concert that raised $140 million in a bid to mitigate the crisis. Sudan’s current situation could be worse and has received only a fraction of international attention, says Dr Timmo Gaasbeek, a food security expert and author to a report by the Dutch think tank Clingendael. “I am very worried that the scale that we are looking at is like nothing we have seen in the last decades, it may well be much worse than [the famine of] 1984 was.”

The magnitude of the food insecurity is similar to the famine of 1984, Gaasbeek told Ayin, but there is a larger population in Sudan, fewer coping mechanisms, and more restricted movement. In their latest estimate, Clingendael believe as many as 2.5 million people could die of hunger by September this year. “It could be higher than this, it could be 5 million people,” Gaasbeek said. “And if the October harvest season is not good, there will also be famine next year.

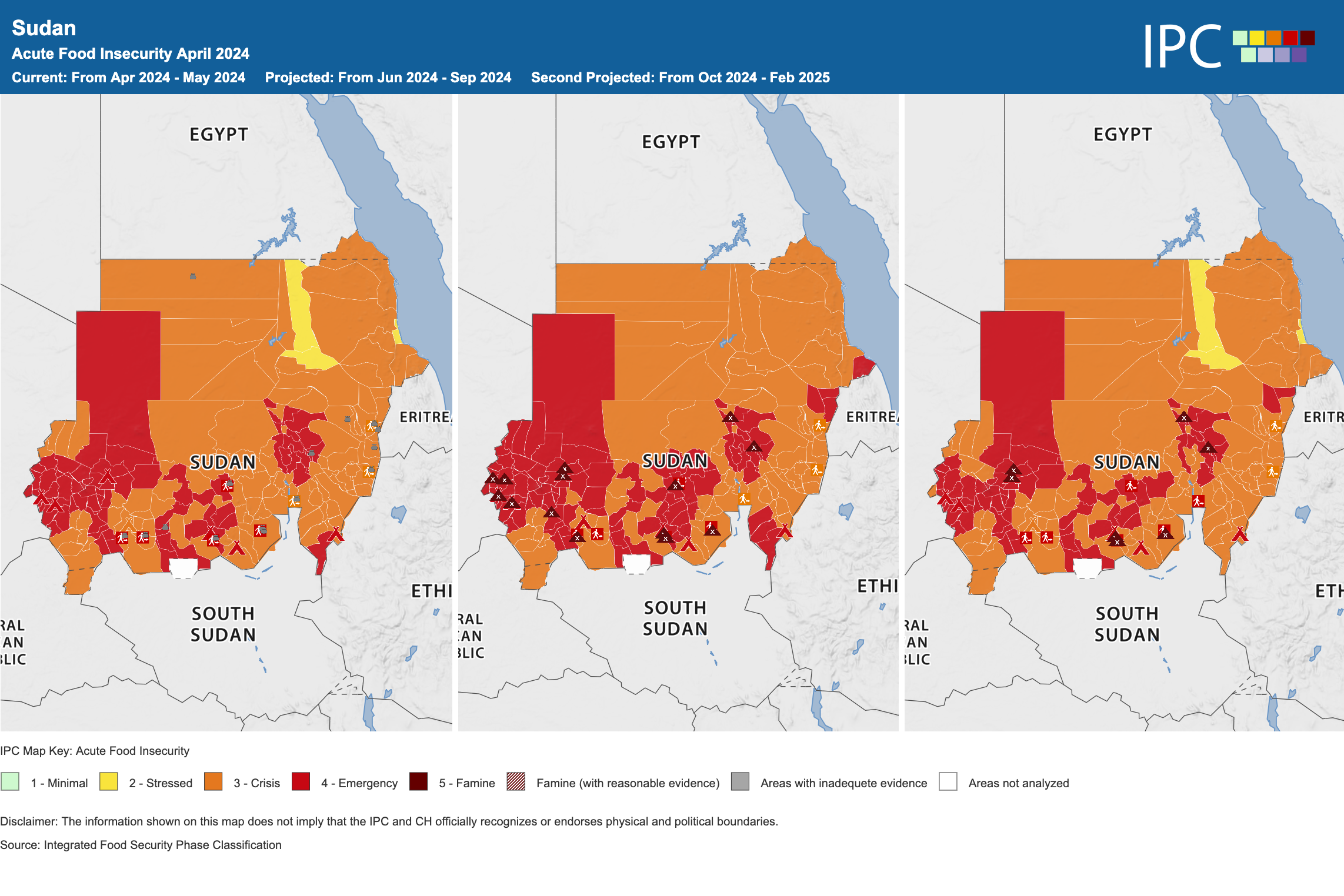

According to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), an expert group of UN agencies, aid groups, and governments that measures the food crisis, there is a risk of famine in 14 parts of the country. The IPC has never seen such a high level of acute food insecurity in Sudan as it is today, which is close to 26 million people.

As the war between the army and paramilitary Rapid Support Forces surpasses 15 months, neither side has shown any genuine interest in peace negotiations, even allowing humanitarian access to the conflict affected.

Darfur and Kordofan

The Darfur and Kordofan regions are particularly prone to famine, Gaasbeek said, due to the dearth of food being delivered from eastern Sudan across the Nile to the western regions. “It has become much harder to get food from the east of the country across the Nile,” Gaasbeek told Ayin, “because you need to go through Wad Medani, and now with the fighting in Sennar, it’s even harder.” The UN reported in mid-June that two vital cross-line routes to Darfur and Kordofan are impassable due to “active violence, security operations, and bureaucratic impediments.” Both Gedaref and Sennar states in eastern Sudan have managed to have reasonable harvests this year, he added, but this food is not reaching western Sudan. Even before the war, the Darfur region generally did not produce enough food to feed its population and depended on imports from other parts of the country.

“Children are badly malnourished. There is no food, medicine, or anything,” says Um al-Hassan Ahmed, a displaced woman who fled the violence of El Fasher and is now residing in Tawila, North Darfur State. According to Yousif Adam, the Humanitarian Affairs Coordinator for Tawila District, no humanitarian organisations have been able to reach the area to support a growing number of conflict-displaced people. The same applies in Atbara, a city in River Nile State on the other side of the country. “We do not receive any support from international organisations,” says Mustafa Ibn Aouf, a volunteer in Atbara’s Emergency Response Room, a volunteer collective that supports the conflict affected. “The aid solely comes from the people of the area—those in Sudan and abroad.”

In the case of Adré Refugee Camp in Chad, a stone’s throw away from the restive capital city of West Darfur State, El-Geneina, the World Food Programme has been able to deliver some food to the conflict displaced, says volunteer Bader El-Deen Ibrahim. But it is never enough. “The aid comes to a specific number of people,” El-Deen explains, “Yet the people increase on a daily basis. Therefore, some people do not get anything.”

No aid, no access

In many cases, there is simply not enough aid to meet the needs of Sudan’s ongoing humanitarian crisis. In 2022, before the conflict, the UN’s World Food Programme (WFP) supplied four percent of Sudan’s grain supply. Now it must scale up at an unprecedented level but lacks the funds to do so. According to the UN Humanitarian Coordinator for Sudan, Clementine Nkweta-Salami, only 32 percent of their humanitarian appeal is funded, and it is already more than halfway through the year. “I am urging donors to urgently step up to disburse their commitments and identify new funding if humanitarians are to stand a chance at preventing a large-scale famine from taking hold,” Nkweta-Salami said in a statement. To many, especially children in displaced camps within the country, famine has already reached them. In March, the charity Save the Children reported that 2.9 million children are acutely malnourished, with 32% of them likely to die if life-saving aid is not provided.

But even if aid is available, there is no guarantee either warring party will allow aid to be delivered. “We have by now various independent reports that suggest the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) are both using starvation as a weapon of war,” says Anette Hoffmann, an Aid Policy Expert and Senior Research Fellow at Clingendael. “In short, aid efforts that rely on the army and their permission to fight hunger risk achieving the exact opposite.” In June, the UN reported that roughly 1.78 million people were denied crucial humanitarian assistance due to violence, logistical constraints, and travel approval delays. Nearly 836,000 people in Darfur, 617,000 in Kordofan, and 114,000 in Khartoum received no assistance. At times, the Humanitarian Aid Commission under the de facto army government demands as many as 4-5 different stamps for an aid convoy to travel outside of Port Sudan, a humanitarian aid worker told Ayin. “Bureaucracy is literally killing people; it is all part of their stratagem,” the aid worker said on condition of anonymity.

Famine by any other name

Fearing even greater restrictions, the UN abides by the military government’s rules and seeks their authorization for aid deliveries. And if the army does not declare a famine in Sudan, a position they routinely adhere to, neither will the United Nations. Despite the IPC warnings of famine, a UN body that serves to inform timely action to mitigate food insecurity, the UN has not officially declared famine is taking place in Sudan. By not doing so, Hoffmann says, the UN loses a key opportunity to mobilise funding and ensure more global political traction for the country.

“The UN is very reluctant to call the situation by its name in order to please the government and retain the little (humanitarian) access they have,” Hoffmann adds. “But I think we are reaching the situation where we have to ask ourselves, to what extent there is more to win than to lose because less than 10% of those who urgently need humanitarian assistance have been reached by the UN system.”

Think local

Instead, new tactics must be used to ensure what little humanitarian aid is available reaches Sudan’s vulnerable populations. One general solution, Hoffmann espouses, is to think local. Traders and merchants in Sudan can still access markets that international humanitarian actors cannot. Most importantly, local community kitchens under the Emergency Response Rooms, where volunteers risk their lives to support one another, need to be entrusted to donors and the international community, Hoffmann said.

“Our conventional toolbox for humanitarian aid is not able to meaningfully address this crisis. The ERRs are currently the only functioning, meaningful aid system we have in place; they need to be fully entrusted. In addition, international in-kind food aid, water and sanitation support, and cash-based assistance must be brought to scale and done in cooperation with non-traditional partners such as governments from the Gulf and the private sector.”