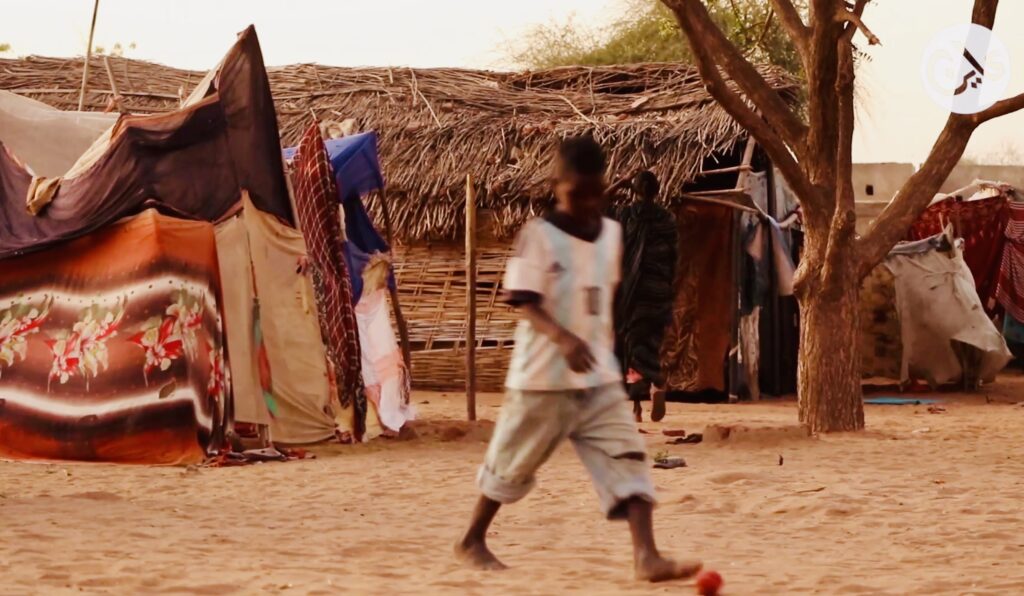

Five areas in Sudan face famine, five other areas in North Darfur may soon follow

Kawthar Adam sits with her children inside a building constructed with local materials in Abu Shouk camp for the displaced, north of El Fasher city, North Darfur state. Since 24 January, the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have shelled the camp incessantly. According to one source within the RSF not authorised to speak to the press, the shelling is meant to oust soldiers allied to the army. But there is little to zero accuracy in these attacks, the RSF source concedes.

Kawthar Adam is terrified. So scared, she told Ayin, she momentarily forgot the hunger that also threatens her life. The constant shelling has prevented her from looking for food for herself and her children. All the markets and commercial stores in Abu Shouk camp were closed for the same reasons, with no opportunity to leave the area at all.

With nothing left but table salt and peanut seeds, Kawthar mixed them with drinking water to give her children to temporary placate them. She remained in this condition for a week, fearing that her children would eventually lose their lives due to hunger as the fighting continued around them.

Kawthar Adam’s situation applies to millions of Sudanese suffering from severe hunger in the Abu Shouk, Zamzam, and Salaam camps in North Darfur State, in addition to areas in South Kordofan State and the western Nuba Mountain region, according to the latest results from an international famine review committee under the UN’s Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) system.

Devastating levels

“Humanitarian suffering in Sudan has reached devastating levels, with more than 11.5 million people internally displaced and another 3.2 million seeking refuge in neighbouring countries,” said Edem Wosornu, Director of Advocacy and Operations at the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), during a UN Security Council meeting on the protection of civilians in Sudan.

“Sudan is facing a humanitarian crisis of staggering proportions, a man-made catastrophe caused by an unrelenting conflict that has dismantled food systems and vital infrastructure, leaving millions at imminent risk, with 90 percent of displaced families currently unable to afford food,” the UN official said.

The latest UN findings suggest five areas are currently experiencing famine and another five areas, all in North Darfur State, may also be affected by May this year. The report warns that 17 other areas are also at high risk of famine if urgent intervent is not taken. “Key areas in South Kordofan are effectively cut off from outside aid,” she added, while “visas for humanitarian workers are not being granted quickly enough.”

Farmers in Darfur

Roughly 2/3 of Sudanese rely on farming for the country’s food supplies, food security expert Dr. Timmo Gaasbeek told Ayin. This is one reason why the curb in agricultural production due to the conflict in key states such as Al-Jazeera, Sennar, and South Kordofan has had such a devastating impact.

“Dilling is one of the most populated areas in South Kordofan State. It is under complete siege from all directions by the army, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), and the Rapid Support Forces (RDF) from the north,” says Asmaa Ahmed*, a volunteer working in the community kitchens under the Emergency Response Rooms (ERR) in South Kordofan State.

“No aid or food supplies have reached it for months. In addition, it includes about 35,000 displaced people who came from Habila and several areas that witnessed military clashes,” she told Ayin. She added that a a small harvest has reached the town recently from nearby crops but this will likely run out in a few days, “and the humanitarian situation will return to square one.”

Ahmed stressed that the displaced are the most suffering, and live under poor humanitarian conditions, as they have no options to obtain food, except for some efforts made by emergency room volunteers. The challenge is access, she added, as few can find safe paths to reach them.

No access

Since the conflict began, humanitarian organisations have struggled to attain access to deliver aid as both warring parties claim aid corridors also act as conduits for arm shipments. On 20 January, for the first time in over a year, desperately needed World Food Programme (WFP) aid arrived in Wad Medani, Al-Jazeera State, providing food for roughly 300,000 people for a month. Unfortunately, these success stories are few and far between, WFP says, as they continue to reach famine-stricken areas such as Zamzam camp. “We need safe access, aid flowing through every border crossing and increased global support to scale up our response,” WFP Executive Director Cindy McCain said.

Access issues plagues the capital of South Kordofan State, Kadugli, and its surrounding areas, says ERR volunteer Issam Mohamed, who works in community kitchens to support the conflict-affected. “The agricultural season in Kadugli and its environs have failed due to the armed conflict. Food products and commodities can only be accessed through one outlet, which is the ostrich market on the border with South Sudan,” Mohamed told Ayin. With limited access, prices remain prohibitively expensive –to the point where even if food is available, few can afford it. “Prices are very high and not within the reach of citizens.”

In early January, both OCHA and the FAO appealed for international support during a UN Security Council briefing, urging governments to priortise funding. The Sudan Humanitarian Response Plan 2025 calls for $4.2 billion to support 21 million people, with an additional $1.8 billion needed for refugees in neighboring countries.

In denial

Sudan’s military-led government suspended its participation in the Global Hunger Monitoring System just ahead of the IPC report. In a letter dated 23 December, Sudan’s agriculture minister said the government had suspended its participation in the IPC system, accusing the IPC of “issuing unreliable reports that undermine Sudan’s sovereignty and dignity.”

A recent Reuters investigation found that the Sudanese government obstructed the work of a humanitarian assessment committee earlier this year, delaying the determination of famine in the Zamzam camp for internally displaced people by several months.

According to volunteers in the community kitchens in Omdurman, this denial of widespread hunger takes place while people are struggling to survive, even in government-controlled areas such as those in Omdurman.

“The people of Omdurman are living in poor humanitarian conditions,” says Mohamed Doulbait*, one of the volunteers working in the ERR community kitchens. “The lives of most of the people depend on our kitchens, which do not have the capacity or capabilities to cover the needs of all families, in light of the very high prices of food and the security threats resulting from the random artillery shelling of the area.”

* The name has been changed to protect the identity of the source.