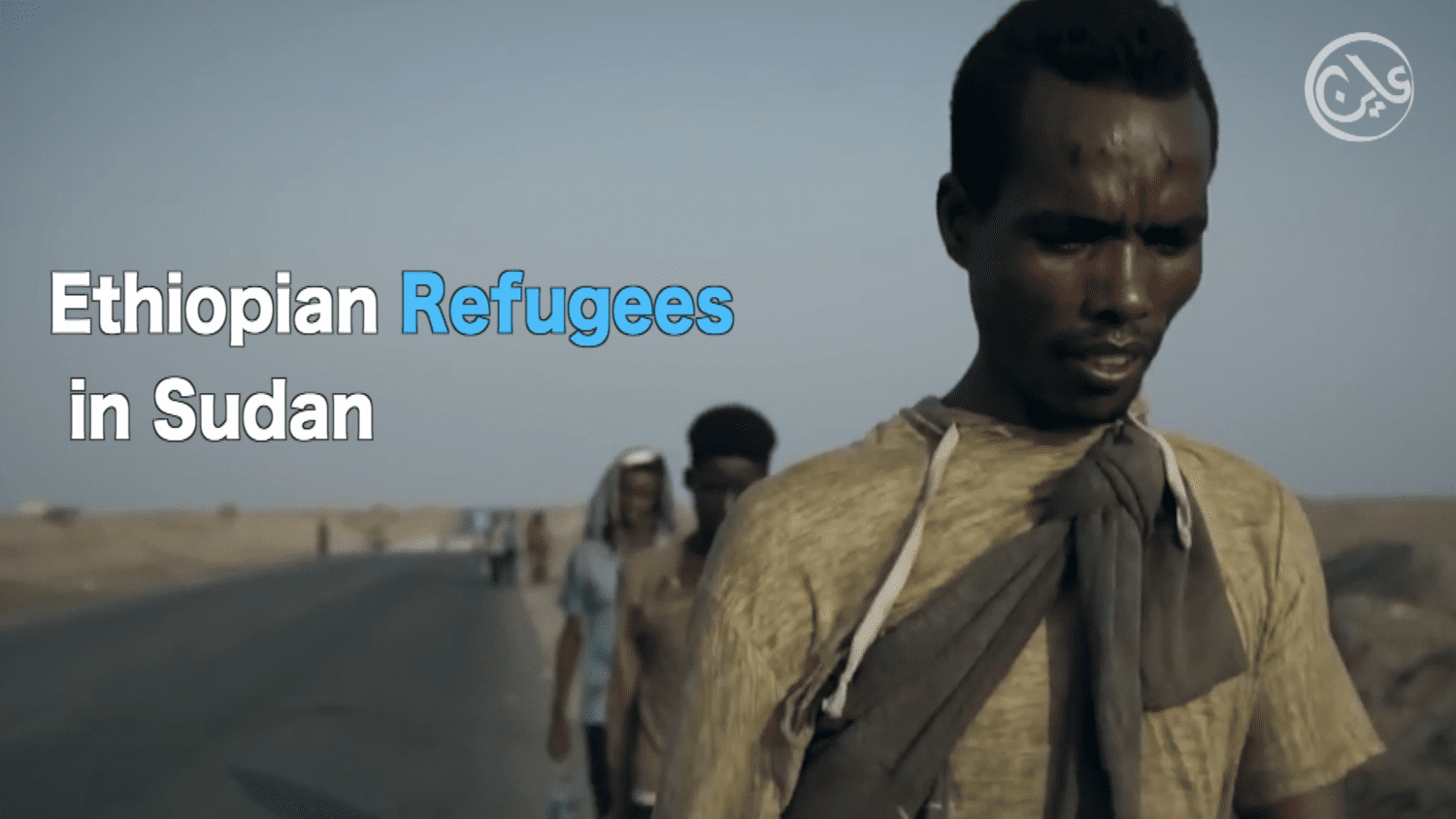

Ethiopian refugee crisis continues in Sudan with no clear end in sight

25 November 2020

As the fight continues in Ethiopia, refugees continue to flood across the border, only to face humanitarian challenges in Sudan. Questions remain whether humanitarian actors will be able to contend with the humanitarian crisis and whether the conflict in Ethiopia will continue –invariably adding to the influx of refugees into Sudan. The UN estimates refugee numbers have surpassed 40,000, the majority being women and children.

Three weeks of conflict in Ethiopia’s Tigray region between the federal forces of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and the Ethiopian national army has driven people from their homes to the Sudanese border. Refugees are entering two border transit centres via Hamdayet in Kassala State and Lugdy in Gedaref State, where aid agencies assist them before being transferred to a permanent refugee settlement.

Humanitarian Crisis

Adish Sulimano fled her hometown in Tigray, Abdulrafae with her young daughter after it was bombed by the Ethiopian army. Sulimano managed to hide herself and her daughter inside their home when the shelling took place at night. “In the morning all the residents of the town had run for their lives, I saw too many corpses scattered and injured women and children along the way,” Sulimano told Ayin. “I don’t know where my family members are, we arrived in al Hashaba border area with thousands of refugees. We are a big family, but I don’t know if the rest of us made it to safety or died back home.”

Other refugees found themselves fleeing from Tigrayan forces. “When I escaped to Hamdayat, I was not in the military combat zone but there was another battle and chaos created by a Tigray militia that terrorised our area,” according to refugee Guday Alam.

One aid worker at the Lugdy transit centre told Ayin that they are facing shortages of basic supplies including food and materials for shelters. “We meet people when they first come and give them energy biscuits and identity cards to acquire basic food supplies. The camp they (will) stay in had been closed for a long time and needs maintenance, lacking the basics –there are challenges in terms of sanitation as well as the fear of the spread of covid-19.”

Challenging transit conditions

MSF (Médecins Sans Frontières-Doctors Without Borders) has set up operations in both transit centres –Hamdayet and in al Hashaba—as well as collecting materials to set up operations in the new refugee camp, Um Raquuba. “We are implementing our first response that will include clinics for primary healthcare, water and sanitation such as constructing showers and toilets and access to clean water”, says Jean-Nicolas Dangelser, Head of Mission in Sudan for MSF-Holland.

Dangelser told Ayin their doctors in Al Hashaba are doing more than 600 consultations per day and have identified the main health challenges as malaria, leishmaniasis, pneumonia and other respiratory tract infections. “While the other diseases are commonly identified in displaced populations, the high levels of leishmaniasis are a surprise to us”, adding that mental health is also one of their first issues to address as most of the refugees received are highly traumatized.

The fear of the coronavirus spreading among the influx of refugees is, naturally, another concern. Organisations are looking into doing screenings at the transit centres but aid agencies admit their ability to curb it spreading is limited. “We are currently struggling to cover basic needs such as drinking water, so asking refugees to wash their hands is difficult. People are focused on food, water and shelter – while important, it is very hard to get [the displaced] to adhere to preventive measures to stop Covid.”

Logistical nightmares

While the influx of health needs are great, so too are the logistical challenges. The refugees are meant to be relocated from the transit centres after a 24-hour period before being taken to the permanent refugee camp, Um Rakuba. Buses are being prepared to move refugees for the 12-hour bus ride from Hamdayet, while a ferry is required to transport refugees across a river from al-Hashaba. With a massive fuel crisis plaguing the country, moving 30,000 people with 22 buses is no easy feat, he added.

Even when refugees arrive at Um Rakuba, it is a long journey to nowhere, other aid workers told Ayin. Aid workers not commissioned to speak to the media told Ayin on condition of anonymity that refugees are being dropped into the new camp that is essentially empty land and sleep under trees.

Conflicts continue

Despite all sides being affected by the war, conflicts between the two prominent refugee communities, the Tigrayan and Amhara, continue within the camps –forcing aid agencies to support them separately. “Each ethnicity accuses the other of their current predicament,” the same aid workers told Ayin. “Tensions within the refugee camps will likely be high months to come.” Alex Bisschop, the UNHCR representative in Sudan, stated to the press that soldiers also crossed the borders and they are managed separately from civilians.

War at home

War at home

Tensions between the Tigrayans under the federal leadership of the TPLF and Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed have persisted ever since the premier took power in 2018. The Prime Minister has accused the TPLF of resisting the national government –even instigating insecurity, while the TPLF claim he has consolidated power and dismantled Ethiopia’s federal political system. Troubles go back to August when Ahmed delayed federal elections citing concerns over the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic. The TPLF ignored this directive and held elections in September, prompting the premier to cut funds from the TPLF leadership in the Tigray capital, Mekelle. On Sunday, PM Ahmed issued a 72-hour ultimatum to Tigray’s forces, telling them to surrender as they were “at a point of no return”. But Tigray’s forces have vowed to keep fighting, with their leader Debretsion Gebremichael saying they are “ready to die in defence of our right to administer our region,” according to news reports.

The answer lies with Sudan

How long the conflict in Ethiopia and the subsequent influx of refugees into Sudan lasts may be answered by Sudan itself. If Sudan opens its borders to the TPLF, allowing arms and supplies to channel into northern Ethiopia, a protracted conflict could take place, says political analyst and former Ethiopian foreign ministry expert, Chalachew Tadesse.

The TPLF had strong historical ties with Sudan’s previous government, including the security forces. “During the (former president) Omar al-Bashir’s time, the relationship between the TPLF and Sudan was very strong,” Tadesse told Ayin. “He (Bashir) used to fly from Khartoum directly to Mekelle.” Sovereign Council leader Lt.-Gen Abdel Fatah al-Burhan, for instance, was formerly the head of the army under ousted dictator Omar al-Bashir and deployed along the eastern border. With Sudan’s divided leadership between civilian and military authorities, the TPLF may find support from their Sudan’s security forces despite the close relationship between PM Hamdok and his Ethiopian counterpart. Further, with the ongoing disagreement between Sudan and Ethiopia over the Renaissance Dam and historical borderland disagreements, it is unknown which side will Sudan take. Even if Sudan does continue to block TPLF border access, a decisive military victory is not guaranteed for Sudan’s restive neighbour. Ethiopia’s national army may be larger than the estimated 250,000 forces aligned to the TPLF, “but the TPLF have prepared for this war over the past two years,” Tadesse said. “The TPLF generals are experienced, well-armed and resourced.” Whatever the outcome, the plight of Ethiopian and Eritrean refugees entering Sudan appears set to continue.

From the Pan to Fire

Ethiopian and Eritrean refugees had been coming into Sudan in large numbers throughout the past decades, some staying put while others attempt the risky migration route to Europe. Those refugees who live in Sudan’s capital tell stories of discrimination while attempting to eke out a living in Khartoum.

“All foreigners are required to obtain a residency permit to live in Sudan and another permit to work, each costs about 30,000 Sudanese Pounds (US$ 100),” an official source in the Ethiopian Embassy in Khartoum told Ayin. “But most Ethiopians living in Khartoum are refugees who entered the country illegally, and therefore most of them have no papers or legal documents, they are also poor and cannot afford both permits.”

Without proper credentials, Sudan authorities have targeted both Ethiopian and Eritrean refugee communities within the country, raking up fines worth 50 – 100,000 Sudanese Pounds (roughly US $200 to $400) for failure to obtain permits, according to an Ethiopian resident in Sudan, Shumi Kroos. Earlier in November police forces launched a campaign of arrests against Ethiopians who protested this injustice as Sudan’s Humanitarian Aid Commission and UN’s refugee agency failed to address their situations.

At the moment the concerns for the refugee populations flooding into Sudan are less focused on permit papers and more on survival. “When we heard the attack from far away, we took our kids, we didn’t take clothes, we did not take any food, we just carried ourselves,” refugee Asiosse Adness told Ayin. “Right now, my mother is in a camp but she does not know where I am.”