Education denied: the plight of Darfur IDP children

“Some of them want to fly in an airplane or drive by car…right now my eldest wants to be a doctor since he saw one once in the camps…but what can I do to get him there,” questions Amna Nurein Mohamed, an internally displaced person in North Darfur State. “I work doing odd jobs, washing clothes and house help. Sometimes I farm in villages –right now I only have one child in school, the rest are at home,” Nurein told Ayin. Nurein stays in the Naivasha Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camp in Darfur.

“Our education is random, no one takes care of the kids while in school and when they come home since the family is outside the camp farming and looking for work,” she explains. While fathers are working in the city, mothers are searching for food – no one has the capacity to look after their children. “I manage to get home to cook for them and that’s it, the cycle continues.”

Unlike many of her neighbours, Nurein has attained two secondary school certificates but could not afford to attend university. “I just keep my certificates in this house. In this entire camp, you may find only one person [who] has gone to university.”

With overcrowded and underfunded schools in Darfur IDP camps, the children in these camps face huge challenges accessing an education. Often hungry, many IDP children in Darfur resign themselves to finding food and dropping their pens altogether.

Musa Ibrahim is a chief in neighbouring Abou Shouk IDP camp in North Darfur. He came in 2004 when the camp population was 57,000 –now it is over 80,000. Abou Shouk has 18 schools with eight of them being private, Ibrahim said. In 2009, the former ruling National Congress Party [NCP] expelled nearly all-foreign NGOs and took over the private schools the organisations started, the camp chief added.

One of the few international bodies operating in Darfur providing education in the United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF]. “UNICEF targets the most vulnerable children, including IDPs across Darfur,” said UNICEF Chief of Communications, Fatma Mohammed Naib.

The former government under Omar al-Bashir never valued education, according to Sudan education specialist Ali Saeed. This was especially the case in Darfur, he said, where the NCP would ensure education standards would remain low in a bid to control the African tribes in the region.

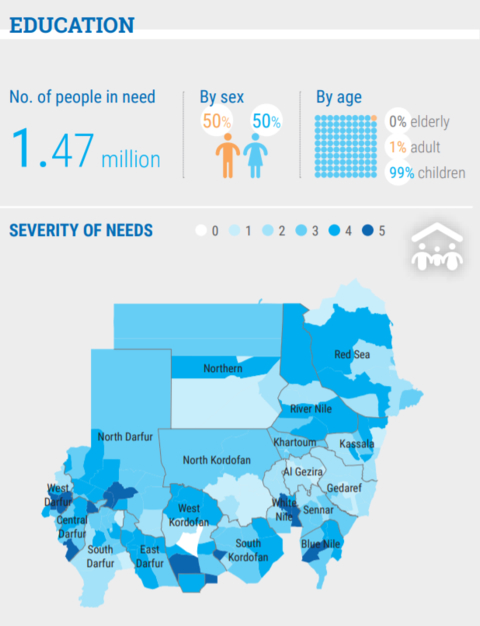

Other regions of Sudan did not fare much better.

Sudan’s 2018 budget only allocated three per cent of its spending to education and 70% to defence and security. In the case of Darfur IDP camps, this has led to too few classrooms for too many war-displaced children.

Over-crowded

According to the International Organisation for Migration, in 2018, 61% of IDPs in Sudan are children. Isaac Abdullah Ibrahim is a primary school teacher in Abou Shouk Camp, he has worked at Korma Public School since 2007 and knows first-hand the challenges IDP children face in the classroom. “The most thing that affects education is over-crowding in the camps,” Abdullah told Ayin. “In one classroom you can get over 80 – 100 students, all in one classroom, crammed on benches. You can maybe help some of the students but cannot ensure all understand the lesson in this setting.”

Korma School has 700 students and only four teachers.

The private schools are generally preferred in the IDP camps since they are less crowded but are generally too expensive for the displaced community in Darfur, residents said. The public schools are meant to be free, Abdullah said, but parents generally pay 600 Sudanese Pounds per month (roughly US$13) to help cover the teachers and volunteers. “The salary we get in one month is not enough for one person to survive, let alone support a family,” Abdullah said, “but I farm to make ends meet.”

In many ways, Korma Public School in Abou Shouk Camp resembles the makeshift houses the IDPs live in. Made of local scrap material, most children are reduced to sitting on floor cushions in a closed, cramped setting.

With such conditions – the school drop out rate is hardly surprising.

According to UNICEF, Darfur states have the highest rates of out-of-school children in the country. A 2018 UN education sector assessment of 30 IDP camps in Darfur found 56% of school-age children lacked access to education.

Empty stomachs

Even those Darfur IDP children fortunate enough to afford to go to school do not stay there for long, Amna Nurein said. “The kids after school in the afternoon are hungry. They cannot understand the last lesson in school –their only thoughts are leaving school to search for food.” Searching for food is the number one priority for all IDP residents, Nurein told Ayin, and this daily search can be extremely dangerous. Many IDPs who venture outside the camp are either raped or killed by pastoralist communities that roam near the camp. “When you go to farm to plant you wonder whether you will survive,” Nurein said, “only 10 days ago my uncle was killed while planting in his farm.”

Boys are particularly affected, Nurein told Ayin. “When he goes to school and cannot find food, he will go to the market to work –selling water, carrying material, often a young boy will become a breadwinner for the family.”

Food aid provided by the World Food Programme are in short supply within the IDP camps says El Tahir Abdullah Bakur, the Social Director for the IDP community in North Darfur State. According to El Tahir Abdullah, only 47% of residents of Zam Zam Camp in North Darfur receive the ration cards used to collect food aid. “Since 2019, no one has received anything since the year began,” he added.

World Food Programme (WFP) External Relations Officer Woo Jung Kim refutes this claim. “In Zam Zam Camp, food was not provided during July and August as Zam Zam community leaders rejected the implementation of the WFP system that serves to ensure that assistance reaches its intended beneficiaries,” Jung Kim told Ayin. “Once the agreement was reached, WFP immediately resumed distribution in September.” According to Jung Kim, WFP provides rations based on vulnerability assessments. Full rations are provided to new refugees while the ostensibly less vulnerable IDPs receive half rations. “That is why there was a change in the rations that the IDPs currently receive in comparison to what they used to receive,” she said in an email.

Hope despite challenges

The long-term effects of this dearth in education could prove disastrous, Saeed said. Without access to education, the chances of boys joining militias and other armed groups as a means of seeking a livelihood are more likely, he said, allowing the cycle of violence to continue.

“There is no future for these children until we get peace,” said Musa Ibrahim “their future has ended too abruptly.”

Despite the lack of schools, many within the Darfur IDP camps value education, Abdullah said. “We even have one student [in our school] who received the highest marks in the state.”

Many Darfur IDPs do have hopes, however, that the new administration will be able to improve the education standards within the camps and the region in general. “We hope that the new government can help us and push a little bit to improve life,” Nurein said. “When you sleep at night, you just wake up wondering what you can do for your children.”