China’s hidden hands: How Chinese weapons are fueling both side of Sudan’s war

3 June 2025

New evidence reveals Chinese-manufactured weapons are being used by both the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in Sudan’s ongoing conflict – a brutal war that has displaced millions and killed thousands.

Despite Beijing’s declared neutrality and repeated calls for dialogue, Chinese arms are surfacing on both sides of the battlefield, raising questions about China’s real position—and whether it is knowingly enabling the war through state-linked companies.

On 28 April, Sudan’s de facto foreign ministry summoned the Chinese chargé d’affaires in Port Sudan to clarify how the RSF obtained Chinese-made FH-95 strategic drones, reportedly used in reconnaissance and aerial attacks on El Fasher and other areas. The ministry raised concerns after the RSF deployed the drones in intelligence operations and targeted strikes on military and civilian infrastructure.

In response, the Chinese diplomat firmly denied any connection between Beijing and the RSF. “The strategic drones used by the RSF do not belong to the People’s Republic of China,” he said, stressing that China “has no relationship whatsoever” with the RSF. He reaffirmed Beijing’s commitment to its official ties with Sudan, adding that “relations between Sudan and China are steadily developing in a way that benefits both parties.”

All trails lead to Norinco

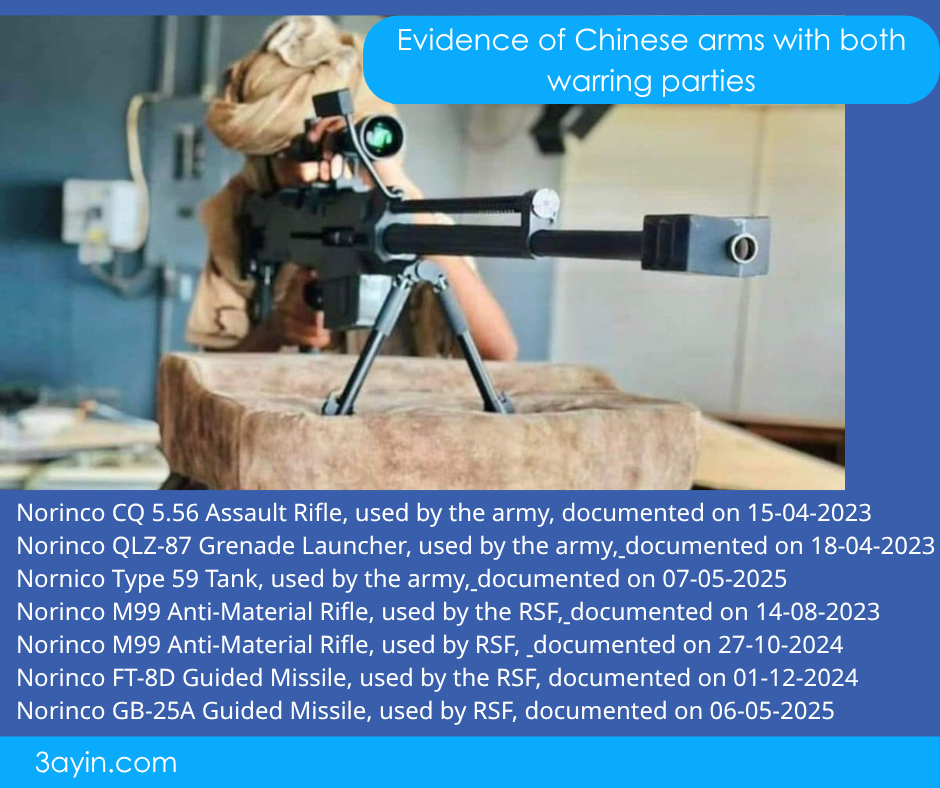

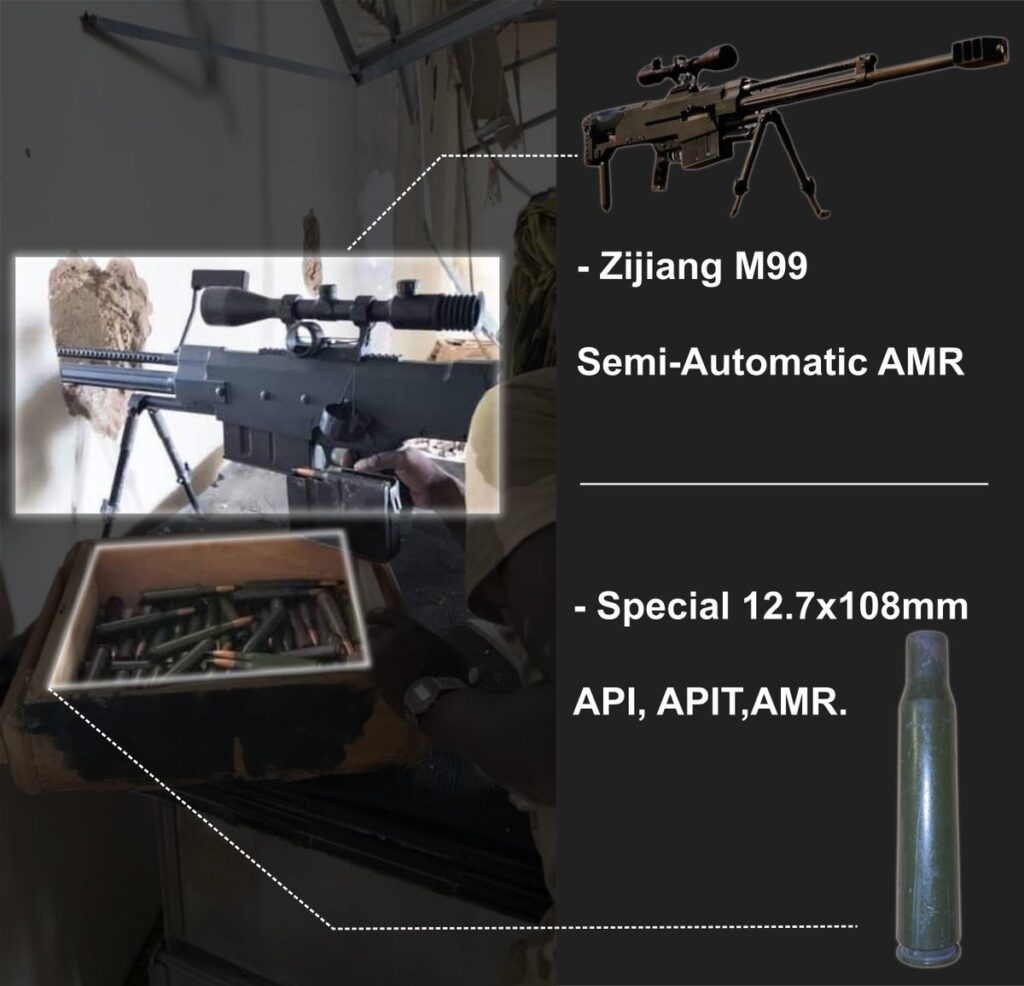

Ayin is analysing the visual evidence of weapons used by both warring parties in collaboration with open-source analyst Faisal El-Sheikh. Across numerous battle sites and verified footage, a consistent pattern emerged: Chinese-made arms, all traceable to Norinco – China’s state-owned defence conglomerate.

Norinco, also known as China North Industries Group Corporation Limited, is one of the largest military contractors in the world. Founded in 1980, it produced a vast range of weapons and systems. In Sudan, Norinco’s role goes beyond exports. The company has long-standing ties with the country’s military-industrial sector, including the licensed local production of Chinese-designed weapons.

Norinco’s footprint also extends into Sudan’s resource sector. The company operates in gold and copper mining and agriculture, positioning itself as both a military supplier and economic stakeholder. This dual involvement deepens its entanglement in the war’s infrastructure and prolongs its indirect influence over the conflict’s direction.

Ayin’s earlier investigation into the Port Sudan strikes uncovered clear signs of Chinese-made weapons. Footage of the Coral Marina Hotel aftermath, aired by Al Arabiya, showed bomb fragments matching Norinco’s GB-25A—an air-to-surface guided munition designed for drones. This same weapon has appeared in RSF-linked attacks in El Fasher and Kassala, pointing to a consistent Norinco footprint across multiple fronts.

Ayin reached out to Norinco for comment, but no response was received by the time of publication.

“Just business”

Kholood Khair, Director of the Confluence Advisory think tank, says China’s role in Sudan’s war reflects its longstanding preference for backing state actors, even as its weapons continue to flow to both warring sides. “China has been politically very pointed in its support for SAF,” Khair explained. “When SAF forces entered Omdurman after the Manama Agreement in February 2024, the Chinese embassy tweeted a picture of the city’s iconic clock tower and wrote, ‘Here is Omdurman’—clearly signalling their alignment with the state.”

Despite this public endorsement of SAF as the legitimate authority, Khair noted that China’s commercial logic follows a different path. “They’re still exporting to both sides because, frankly, both sides are paying,” she said. “We have to separate China’s political posture from its participation in the global war economy, where profit often overrides principle.”

Alberto Fernandez, former U.S. chargé d’affaires in Sudan, described to Ayin China’s involvement in Sudan’s conflict as commercially driven rather than strategic. “China’s main motivation is profit,” he said. “I don’t think China is concerned with who the end user is.”

Beijing’s long game in Sudan

China’s relationship with Sudan is decades old, rooted in oil, infrastructure, and strategic alignment. In the early 2000s, when most Western governments imposed sanctions on Sudan over atrocities in Darfur, China expanded its investments and arms sales. Sudan became one of China’s largest oil suppliers in Africa, and Chinese state-owned firms built pipelines, roads, and refineries in exchange for privileged access to resources.

Khair added that the ties between China and the army date back to the oil boom of the late 1990s and are rooted in long-term strategic interests rather than short-term intervention. “Sudan is critical to China’s Belt and Road Initiative,” she explained. “Its vast, flat geography makes it ideal for infrastructure that connects Port Sudan to the Atlantic. That kind of investment horizon—decades, even centuries—is what shapes Chinese foreign policy.”

That relationship was not limited to economics. China was a major arms supplier to the al-Bashir regime, and it maintained diplomatic cover for Khartoum at the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). After the 2019 revolution that removed former dictator Omer al-Bashir, China cautiously engaged with both the military council and the transitional civilian-led government. But when a full-scale war erupted between the army and RSF in April 2023, Beijing publicly urged peace while keeping its defence industry running.

Political analyst Dallia Abdelmoniem says Sudan’s conflict has exposed the extent to which foreign powers prioritise their own agendas over the well-being of the Sudanese people.

“This war has shown us Sudanese that everyone else’s interests take priority over ours,” she told Ayin. She pointed to the presence of Chinese weapons on both sides of the conflict and Russia’s shifting allegiances as signs of a broader pattern. “Sudan is perfect for actors looking to strengthen and deepen their economic ties and influence regardless of the consequences these actions may have on further extending the war,” Abdelmoniem said.