Art in Sudan and its role in promoting peace

7 October 2025

Art has long been more than a tool for entertainment. Across societies, it carries the power to raise awareness, preserve collective memory, and bridge differences. In Sudan, where conflict has deeply shaped social and political life, art has emerged as both a mirror of society and a possible pathway toward peace. From theatre and music to visual arts and poetry, Sudanese artists continue to highlight the role of creativity in healing wounds, fostering dialogue, and imagining a future beyond war.

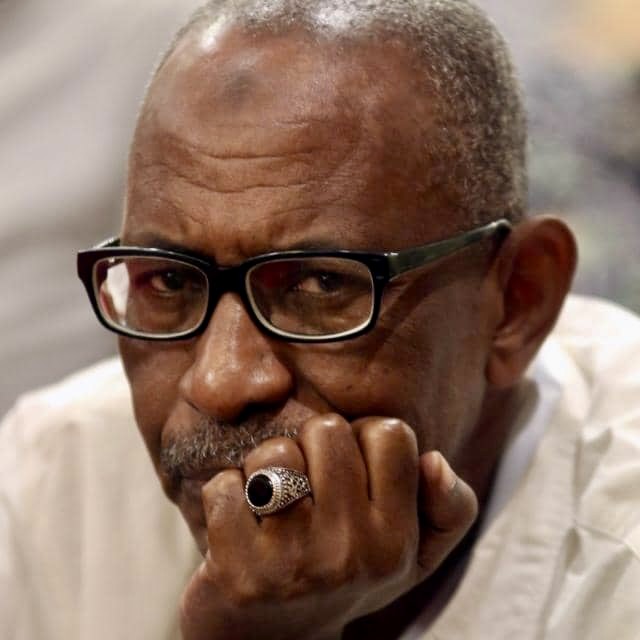

Theatre critic and researcher El-Sir El-Sayed stresses that art, in all its forms, functions as a powerful instrument for peacebuilding. Unlike passive entertainment, art engages people at a deeper level, offering tools to manage conflict and negotiate differences.

“Theatre, music, and popular culture meet people where they are,” El-Sayed explains. “They create shared spaces of understanding. For instance, music can break down cultural, linguistic, or social barriers, and theatre can present sensitive issues in ways that appeal to a wide range of audiences.

Theatre, in particular, relies on universal human expression—gesture, body language, and visual storytelling—making it accessible across divisions. Yet, El-Sayed warns that without awareness and commitment from artists, art risks losing its transformative power. For him, peace is inseparable from justice, freedom, and equality, and art must reflect those values to remain relevant.

Visual arts and cultural diversity

Visual arts also play a central role in Sudan’s peace narrative. Dr Raheel Alarify, an art analyst, describes art as a historic medium for communities to document dreams and struggles. With Sudan’s rich cultural and ethnic diversity, she argues, art should reflect the nation’s pluralism and help foster inclusive dialogue.

During the 2019 sit-in near the General Command in Khartoum, murals and street art became powerful expressions of unity and peaceful resistance. These visual messages celebrated coexistence and called for justice. Dr Alarify recalls how artists across Sudan—both academic and self-taught—used painting as a tool to bring Darfur, Omdurman, and other regions together in one symbolic canvas.

She also highlights the rise of online art exhibitions as a significant development. Through digital platforms, Sudanese artists have found new ways to share messages of peace and solidarity with global audiences, particularly women artists who organised exhibitions such as “Kandakat and Mayarim” that showcased female perspectives on peace and coexistence.

Art as peacemakers

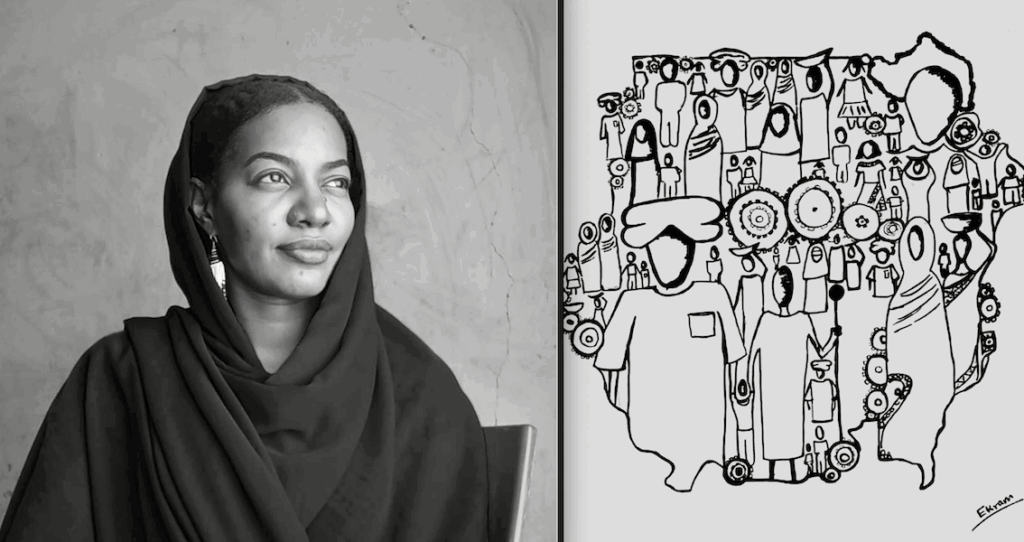

For painter Ikram Hamid, art is a natural bridge between communities. “Art is always a shared language that crosses linguistic and cultural barriers,” she notes. In her view, art is not a luxury but a necessity, offering people a way to express grievances, hopes, and calls for peace.

Ikram also stresses the connection between art and women’s issues. Through painting, music, theatre, and film, Sudanese women have documented unspoken violations and highlighted the resilience of communities in wartime. These artistic forms create empathy, solidarity, and visibility for marginalised voices.

However, she cautions against art that fuels division. Songs promoting tribalism or glorifying violence, she says, undermine the very essence of art. “Real artists,” she adds, “must act as peacemakers.” Art that incites conflict is not art at all.”

For singer Mohamed Khair Osman, art itself is synonymous with peace. “Art refines the human spirit and makes people more accepting of one another, regardless of differences,” he explains. Yet, he admits that Sudan has not fully harnessed the power of art to promote peaceful coexistence. To him, art that promotes division contradicts its essence.

Similarly, poet Mohamed El-Tayeb highlights the dual nature of poetry and song in Sudan throughout history. While poetry can inspire peace and reconciliation, it has also been used to incite war—particularly in the form of tribal poets or hakamat (female praise singers) who encourage men to fight. He argues that acknowledging this duality is essential for reimagining art as a consistent force for peace during crises.

Art as a double-edged sword

The recurring theme among Sudanese artists is the recognition that art can both heal and harm. When art is used to glorify conflict, it diminishes humanity and erodes the sense of solidarity. But when guided by empathy, justice, and creativity, art becomes a weapon for peace.

Dr Al-Arify warns that non-peaceful art not only polarises communities but also undermines innate human compassion. This form of art, she says, can amount to a cultural extremism that weakens society’s ability to coexist. Conversely, inclusive art—whether expressed in murals, music, theatre, or film—provides spaces where diverse voices can meet, challenge injustice, and imagine shared futures.

The Sudanese experience demonstrates that art is never neutral. In times of crisis, it can either deepen divides or help communities rise above them. From murals painted during protests to theatre performances addressing social justice, Sudanese artists continue to shape conversations about peace and reconciliation.

As conflicts persist, the challenge for artists is to remain conscious of their role as cultural mediators. Their task is not merely to entertain but to envision and communicate a collective aspiration: a Sudan built on peace, justice, and coexistence.