Sudan’s warring parties war against peace

2 September 2023

As the war continues in Sudan, the war of words against civilians advocating for peace and an end to the conflict is also taking place. Political activists and civil society actors who call for an end to the fighting are paying a heavy price for speaking up, local activists told Ayin, as their initiatives are met with threats and detentions by both sides of the conflict.

For over four months, a war of dominance has taken place in Sudan between two security forces –the national army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces—with Sudanese civilians stuck in the middle. According to the United Nations Under-Secretary for Humanitarian Affairs Martin Griffiths, the war in Sudan “is fuelling a humanitarian emergency of epic proportions,” with over 4.6 million people displaced and at least 5,000 people killed.

Despite the conflict’s devastation, those who call for its end are shunned -whether in person or online.

“I can no longer look at Facebook,” Atif Suleiman* told Ayin. Suleiman is a part of the resistance committees that helped organise the pro-democracy movement that called for an end to military rule in Sudan –efforts that were purposefully silenced by the warring parties. The resistance committees, Suleiman said, are now assisting with relief operations for the war-affected by providing food and other communal support services. When not helping in the communal kitchens, Suleiman has tried to call for an end to the conflict using social media. “We face threats all the time,” he said, “You may be threatened in the kitchen or online. They don’t want peace [the warring parties] and will accuse you of supporting the other side if you do.”

According to Ahmed Taha*, a member of a resistance committee in Khartoum, the army believes the committees are collaborating with the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) despite the lack of evidence. Conversely, if the RSF encounters resistance committee members in the streets, they are routinely accused of “spying for the army”.

“We Women Say Put the Weapons Down”

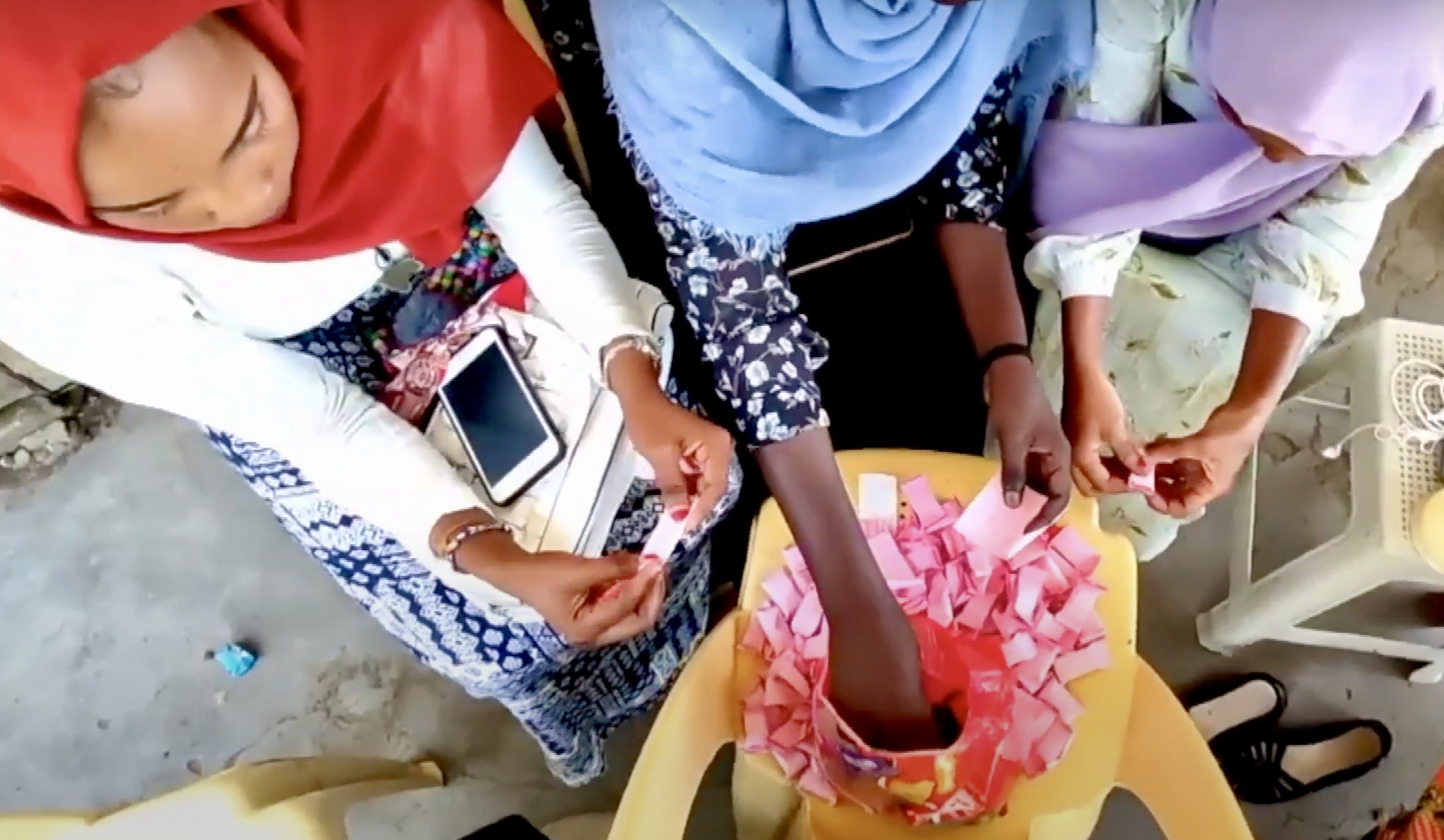

In early August, Sudanese women from the No to Women’s Oppression initiative had planned an event with Sudan’s oldest political party, the Umma Party, at the parties’ headquarters in Wad Medani, the capital of Jazeera State. The event, entitled “We Women Say Put the Weapons Down” was all set to take place, representing a groundswell of voices calling for an end to the war. However, the National Umma Party members changed their minds and refused to host the event.

The event organisers told Ayin unidentified individuals in Jazeera State warned against holding the peace meeting — claiming that the motivation behind the calls to stop the war is supporting the RSF.

To justify their actions, the National Umma Party blamed the fragile security situation and the social media uproar against the event for their decision to cancel the gathering, adding that they hope for the current stability in Jazeera to last and did not want to disturb the tenuous peace. Members of the “No to Women’s Oppression” flatly deny any association with either of the warring parties –whether the army or the RSF—and said their event was designed to spark a women-led, grassroots campaign to stop the war.

“Those who promote war are the ones who influence the crisis in Sudan the most,” Amira Osman, the head of the No to Women’s Oppression Initiative, told Ayin. “The weakness of the civil movement has empowered the warmongers and impaired the anti-war voices.” Osman pointed out that both parties of the conflict are targeting political activists and civil society actors in this regard. Many members of the No to Women’s Oppression group, she added, contend with repeated cyber-bullying via an orchestrated online campaign against them.

Sudan Mothers Imitative

On 30 August, state authorities in Ed Damazin, Blue Nile, abruptly broke up a vigil organised by the “Sudan Mothers Initiative” to commemorate the International Day of Victims of Enforced Disappearances, detaining seven women human rights actors and a journalist in the process. According to one of the Sudan Mothers Initiative activists, Mona Balla, the organisation advocates for missing persons and staunchly opposes the ongoing war, adding that they rejected “the use of sons and daughters as tools of war in Sudan.” During their public event, the Sudan Mothers Initiative vocally called for the end of the conflict, particularly the targeting of civilians, home occupations, and the bombing of civilian homes. It did not take long, Balla said, for local authorities to break up the event.

Anti-war efforts in the restive Blue Nile State have faced such challenges for a long time, says activist Rufaida Khalafallah. The young activist helped set up an organisation, “We Are All People of Media,” that tries to counter hate speech and the war in general. “We had to stop our work in the [anti-war] initiative due to the poor security conditions the country is going through,” Khalafallah told Ayin. Tarteel Atta Al-Manan, another member of the peace initiative, believes the state’s conflict started in the media and then became a physical reality. “How could neighbours kill neighbours?” Al-Manaan asks, “The culprit has to be the accumulated hate speech that inspires such acts.”

The peace initiative in Blue Nile State was launched before the war in April at a time when political actors fuelled ethnic tensions within the state in July last year. The initiative used social media and public marches to promote peace and achieve inter-ethnic harmony in the area, Khalafallah said.

“We wanted to make an impact using videos since we have experience in video production via mobile phones, especially with hate speech dominating social media at the time,” Al-Manaan said. “As the fighting intensified, we became certain that this violence was not spur-of-the-moment, but the result of a long build-up of hate speech.” The two women started a media campaign, broadcasting interviews with anti-war activists and collecting signatures on posters pledging their rejection of hate speech. But the security forces never took them seriously and merely taunted them. “On one occasion, they asked us to take the signatures’ papers so that they could use them to light fires.”

Calls for peace, a risky business across Sudan

In Kosti, White Nile state, youths fear any engagement in peace initiatives will only expose them to arrests, says civil activist Mohanad Ali*. “The youths in the state are aware of the dangers and threats they can face, so there is no direct activity that calls for stopping the war to avoid troubles.” By late June, the head of the army Lt.-Gen. Abdelfattah al-Burhan called on civilians to join the army across the country –authorities in White Nile complied and started a state-wide recruitment campaign using local leaders to help mobilise the process and set up training camps. Any public attempt calling for peace in this environment, Ali added, will inevitably lead to an arrest or worse.

Since the start of the war, activists, and political actors in Gedaref, eastern Sudan, have organised anti-war events calling for peace –often at great personal risk. “The governor of Gedaref State obeys military intelligence and has tightened his grip on activists and volunteers who work on sheltering the displaced people,” political activist Jaafar Khider told Ayin. Khider said that the city’s municipality and the Humanitarian Aid Commission prevented them from helping the war-displaced by evicting them from a youth hostel and then from the Daim Bakur School. Whenever members of the resistance committee in Gedaref support the war-displaced and call for peace, he added, state authorities arrest them under the false accusation of supporting the RSF. “The military intelligence and former ruling party members are promoting the narrative that anyone who rejects the war is considered an ally of the RSF –which is completely false.”

Peace, democracy vs. war, autocracy

For the warring parties, says political analyst Khaled Taha, the calls for peace commensurate with the calls for democratic, civilian rule. According to Taha, those who call for peace are therefore viewed by the warring parties as a threat that must be silenced by taking advantage of the war and lack of supervision. He stressed that the anti-war slogans emerged from the aspirations of the Sudanese for peace and an end to military rule.

“The main cause for targeting the resistance committees and human rights activists is that the warring parties and their allies – including some civil forces who want to reach power through war – realize that the presence of those who seek real change will prevent them from achieving their goals,” Taha told Ayin. The repeated ceasefire breaches are a clear sign, he added, that neither warring party wants a negotiated peace and will only accept a military victory. Further, neither party is interested in a democratic transition, the rallying cry of the resistance committees.

“The civil forces, led by the resistance committees, have consistently called for the military to return to their barracks, and for the dissolution of armed militias, in addition to defining the functional tasks of the army and allowing a space for the civil society [to work].”

Maintaining the anti-war movement, however, remains a challenge as more and more civilians are dragged into the conflict. With the army leader Lt.-Gen. Abdelfattah al-Burhan called for the arming and participation of civilians back in June, Sudanese citizens are increasingly being viewed by the warring parties as potential opponents, says political analyst Khaled Taha.

Despite this military polarisation, activists believe local voices condemning the war will persist. Jaafer Khider believes the national voices calling for peace “may be faint but will continue despite any oppression they are subjected to, whether on social media or in real life.”