The cyclical violence of Blue Nile, a political agenda

28 January 2022

“They attacked us in the morning inside our village. We did not find a way to escape – they carried machine guns and machetes and set fire to our homes,” recalls Samira Zakaria, whose village in Blue Nile State was attacked by unknown assailants in July last year. Samira, who was displaced from her village near Roseires, claims this type of violence was unheard of before in Blue Nile and recalls years of harmony and coexistence with different ethnic groups. “Now we have become displaced and dependent on relief,” she says from an internally displaced persons [IDP] camp in Roseires town, bordering Ethiopia.

“We were at home at the start of the first conflict – a Thursday – then we went out on Friday to visit friends and neighbours,” recalls Thowayba Hafiz, from Wad Al Mahi, Blue Nile State. “But when the second conflict occurred, we had to flee at night. You don’t imagine that people you co-existed with peacefully for years, that became your friends, colleagues, even in-laws, would come attack and assault you.”

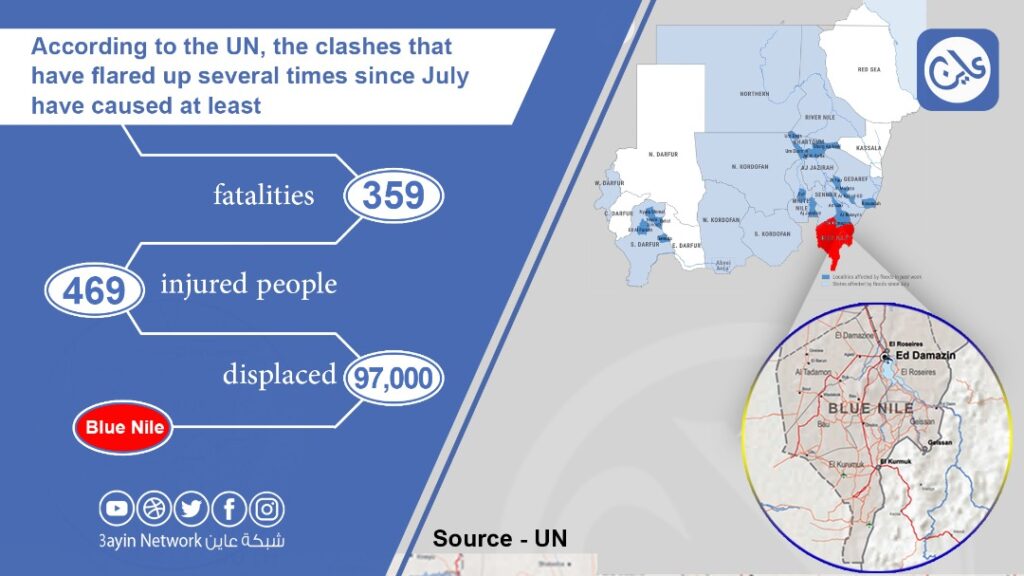

On 14 July, armed clashes between members of the Hausa, Berti and Funj tribes started in multiple areas of Blue Nile state, including Quaisan, the capital Damazin, and Roseires. Since that time, unprecedented levels of inter-ethnic conflict have plagued Blue Nile, with reoccurring violence taking place in September and October, according to Fateh Al Rahman, the General Manager of the state health ministry. The United Nations (UN) estimates 359 collective deaths have occurred in Blue Nile since July 2022 from nine separate incidences of inter-ethnic conflict.

Highest displacement

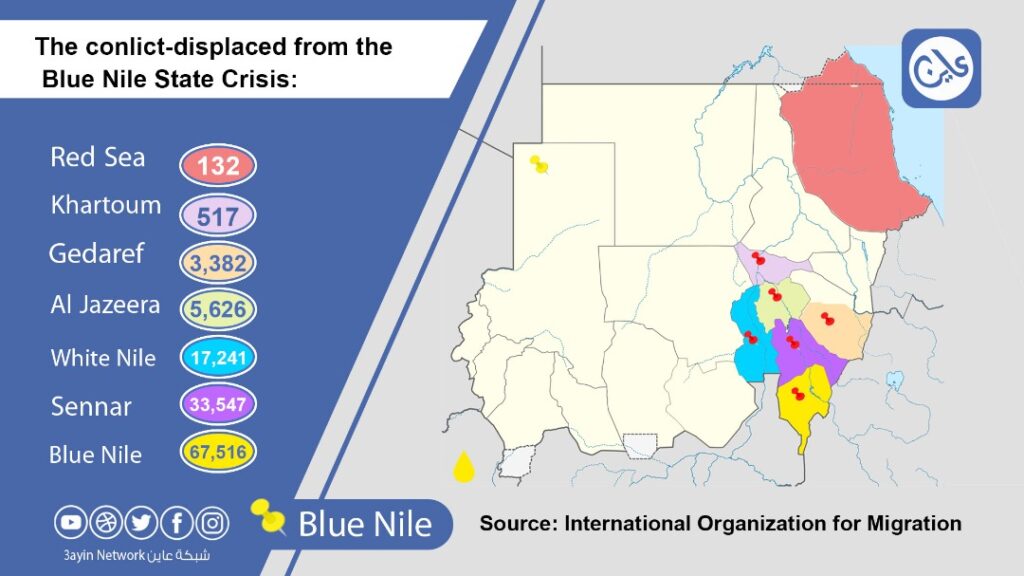

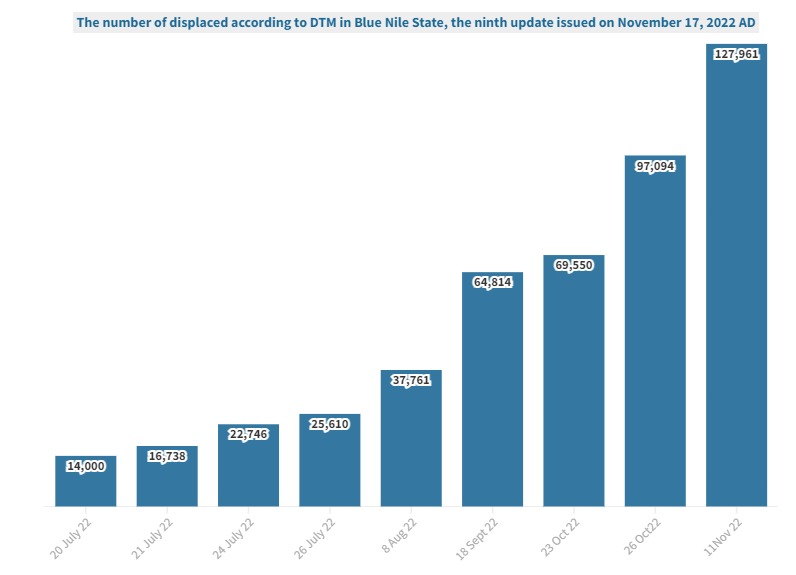

These multiple incidents have provided Blue Nile State with the ignominious title of hosting the most conflict displaced in 2022. According to UN estimates, the state has nearly 128,000 conflict-displaced within its borders; the majority emanating from the inter-ethnic clashes that started in July last year. Other victims of the violence have fled outside of the state with large numbers moving to neighbouring White Nile and Sennar states.

Roughly 30% of those displaced in Blue Nile State are residing in schools and other public buildings found in Damazin and Qaisan. According to humanitarian worker Husna Abdelqader, the displaced are now in need of winter clothes and blankets to contend with the cold months, in addition to food and medicine. Several international national organisations are supporting the IDPs, Abdelqader told Ayin, but the number of displaced overwhelms the support provided.

Government authorities have attempted to quell the repeated cases of violence. On 15 January, a reconciliation meeting took place in the presence of the Sovereign Council Head, Lt.-Gen. Abdelfattah al-Burhan. An agreement was signed that stipulated mutual cultural and historical respect for the state’s diverse ethnic demography. “The agreement is a first step and requires hard work and concerted effort from all parties,” announced Burhan during an address at the signing ceremony in Damazin. “We will continue to try and reach a comprehensive and solid [peace] agreement.” Last Tuesday, Blue Nile State Governor Ahmed Al-Omda extended a state of emergency in the state for another 30 days to curb inter-ethnic violence.

For Damazin residents, the capital is no longer the lively, bustling town of the past. People venture out to the market and streets with a sense of trepidation, fearing insecurity despite a mass military deployment patrolling the area. Many residents told Ayin they live with this uncertainty since they do not understand the roots of the conflict and who may have perpetrated it.

Why the violence?

According to Blue Nile State Governor Al-Omda, the issue started in April when the Hausa tribe demanded their inclusion into the state’s administration, the official said in a televised interview. Earlier in the year, the governor said, the Hausa community had chosen a leader to represent their affairs – a move that was rejected by the tribal administration in the region. The head of the Blue Nile’s tribal administration, El-Obaid Hamad Abu Shotal, openly questioned the Hausa’s demands for representation, claiming the area belongs to the “tribes of the Blue Nile” and that the Hausa were “guests” to the area.

While many Hausa have lived in Sudan for generations, other tribes in the state still perceive them as outsiders since the Hausa ethnicity is particularly prominent in West Africa. Some residents also claim the Hausa are favoured by the current military rulers since they supported the former National Congress Party under Omar al-Bashir in the past –-a claim many Hausa dispute.

“If we were to identify the source of this conflict; it started between a group that calls themselves ‘the grandchildren of the Blue Nile sultanate’ and the Hausa ethnic community,” says Sheikh Al Dood Bekhote, the Secretary General of a faction of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N). “There was a conference held by the first group, and some of the issues discussed included the expulsion of Hausa from the Blue Nile region.”

The SPLM-N led by Malik Agar is one of the signatories to the Juba Peace Agreement and supported the military coup of 25 October 2021. Since signing the Juba Peace Agreement, this faction of the SPLM-N control Blue Nile and Agar shares power with the coup leaders in the Sovereign Council.

But many residents simply cannot accept this explanation for the repeated bloodshed and suspect certain perpetrators have helped foster the violence. “It makes no sense that after years of people living together in an area, co-existing and having relations, that suddenly it gets decided that a specific ethnicity is unwanted and they should leave,” says Wad Al Mahi resident Thowayaba Hafiz. “This land is god’s land; no group of people are more entitled to it than others.”

Heavily armed attacks, no security

While difficult to prove, many residents suspect the security forces played a role in instigating the conflict in July. For one, security forces made no effort to mitigate the violence and the perpetrators of these attacks were heavily armed from unknown sources.

In stark contrast to the crackdown on anti-coup demonstrations, security forces are accused of standing back and allowing armed violence to unfold for three days, from 14 – 17 July 2022. “There was a confrontation with firearms – it lasted from 10 or 11 am up until the evening,” recalls Damazin resident Ezeldeen Al Naiem. “The official forces did not intervene, which left people to defend themselves as they see fit.” Residents said military reinforcements to protect civilians came only two months later in October.

Even local officials blamed the state leadership for the lack of security. In a television interview, the mayor of the Wad al-Mahi locality, Abdulaziz al-Amin, said security forces were withdrawn shortly before the outbreak of violence in July at the behest of the state governor. The dismissed forces were meant to be replaced by other troops, al-Amin said, but these forces did not report to duty on time. “We were not consulted about this replacement and that decision was made by the regional government,” he added.

Former Sovereign Council leader Mohamed al-Faki Suleiman also accused the military leadership of fanning the flames of inter-tribal violence saying the conflict in Blue Nile state was “a carefully planned matter,” and that these inter-ethnic conflicts always “start in Khartoum and not in the regions of Sudan.”

Residents across Blue Nile State also told Ayin of the heavy use of firearms in Damazin and nearby areas during these attacks and question the potential source of these weapons. “You can see children on the streets, people displaced [and] there is no way for these people to go back home now,” said Saad Khamies, whose village near Wad al Mahi was attacked last year. “We were gravely impacted – they came and attacked us in our homes without a reason. They came well-equipped with weapons and likely still have them. We do not know if they [received these weapons] from the governor or the SPLM-N, but we know that the government is aware.”

SPLM-N under Malik Agar

The Communist Party has also accused Agar’s SPLM-N faction of stirring up ethnic tensions within the state by supporting the Hausa community in return for Hausa recruitment to Agar’s SPLM-N forces. The main SPLM-N wing under Abdelaziz al-Hilu has claimed in the past that Agar’s faction does not control any territory within the state and maintains few soldiers in its ranks. According to Communist Party member Osman Saeed, the SPLM-N faction lost considerable local support after siding with the military and supporting the coup and is now desperate to replenish its forces.

Some Blue Nile residents such as community leader Salah Idris in Kerma, concur. “The regional government affiliated with the SPLM, led by Malik Agar, began recruiting on a tribal basis unilaterally and supplying weapons to support their position in upcoming elections,” Idris told Ayin. “Tribal problems are always solvable between parties –-but the ongoing conflict is being managed and driven by outside parties.”

Malik Agar and his SPLM-N faction, however, flatly deny these claims; instead pointing the finger at political leaders from the former ruling party under Omar al-Bashir. “Blaming the SPLM-N for this is a faulty accusation and those who make this claim should provide evidence,” the SPLM-N Secretary-General told Ayin. “The leadership of the movement does not include any influential leaders from Hausa, and we do not discriminate against any groups; anyone who wants to join is welcome.” According to an SPLM-N statement, the SPLM-N faction has documented proof that the former ruling party militia, the Popular Defence Forces, was involved in the tribal clashes.

While Blue Nile residents may never learn who helped instigate the tribal violence that has plagued the state, they are determined to end it. “There is no winner in these tribal conflicts, we all lose,” Ezeldeen Al Naiem told Ayin. “Personally, my children cannot go to school for example. Those who seek power and political gain should think about how they are impacting people and children.” According to Al Naiem, it is up to local communities to solve these tribal differences through local mediation and never let these efforts be linked to politics. “Returning to a peaceful co-existence takes willpower, not just among the people, but also from both national and regional governments. It needs cooperation.”