Sudan’s oil sector on the brink of collapse

4 December 2025

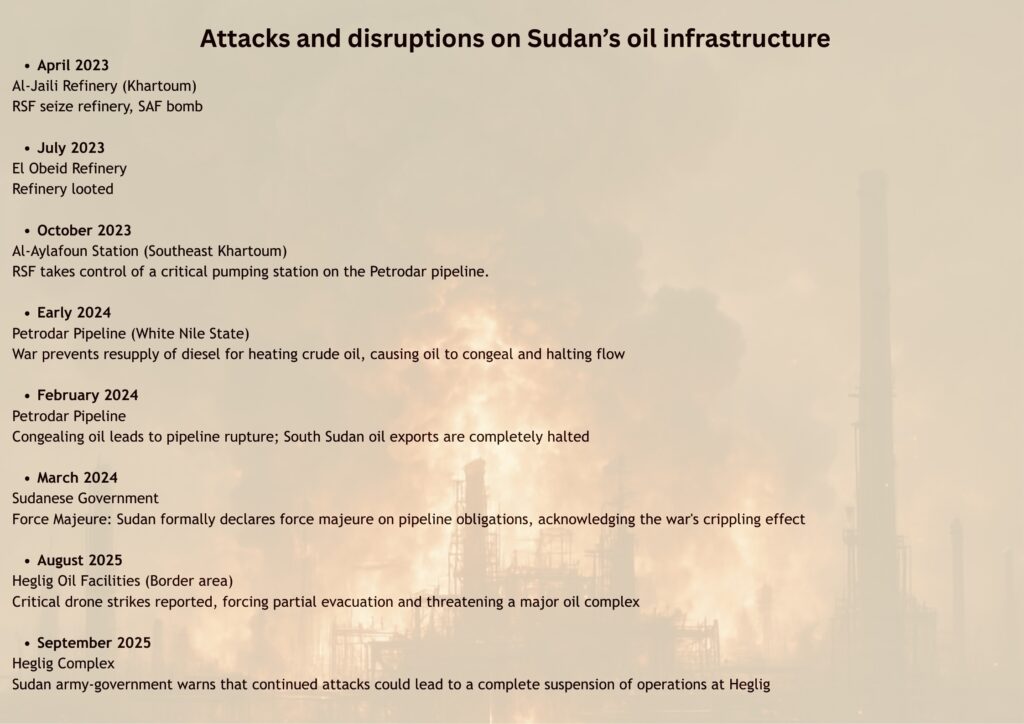

Sudan’s oil sector is inching closer to collapse as the war between the army and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) spreads around vital facilities in the country’s western regions. Fighting, drone strikes, and political tensions have repeatedly hit pipeline operations from oil pumped from South Sudan, and field production in West Kordofan State.

According to Energy Minister Mohamed Abdallah, Sudan has lost roughly half of its oil production since the outbreak of the war in mid-April 2023.

Prior to the conflict, Port Sudan would earn roughly $146 million per month in transit and processing fees from crude oil transported to it from South Sudan. Rough production estimates suggest that the conflict has targeted pipelines, potentially reducing this figure to $48 million at best.

In March 2024, Sudan’s Ministry of Energy declared force majeure on oil exports due to a major rupture in the oil pipelines caused by the conflict. For seven months, Sudan received no revenues from transit fees for South Sudan’s oil, while Juba lost an estimated $7 million per day in oil revenue. Oil production from South Sudan to Sudan only restarted in late December 2024, at half the pre-war rate, from roughly 150,000 barrels per day (bpd) to 90,000 bpd.

The RSF seized the Balila field two and a half years ago, drawing oil fields in West Kordofan—long considered insulated from direct combat—into the conflict. Industry sources warn that the RSF may now target the Heglig field, one of the army’s last major strongholds in the region.

Security strains between Juba and Port Sudan

A member of the Sudanese Oil Workers Association told Ayin that the war’s security fallout has strained relations between Khartoum and Juba, noting accusations by Sudanese officials that South Sudan “has not remained neutral” and may be facilitating Emirati-linked projects tied to the Rapid Support Forces.

Energy researcher Hani Osman said Sudan increasingly views South Sudanese oil transit through a political lens, pressuring Juba to maintain a stance against the Rapid Support Forces. Despite repeated attacks—including drone strikes on Heglig in mid-November—shipments have continued. South Sudan currently pumps about 70,000 barrels per day, roughly 63% of its pre-war production levels, from the Palogue fields to Bashair port via Sudanese territory.

Yet reliability has sharply declined, even with this depleted production level. A Heglig-based employee warned that crude flows from South Sudan “could be halted at any moment as long as things are complicated between the army, the Rapid Support Forces, and the Salva Kiir government.”

A diplomatic source told Ayin that Port Sudan officials conveyed to South Sudan’s Foreign Minister Monday Semaya Kumba during October 2025 talks that Juba must ensure “flexible and friendly relations” with Khartoum to protect its economic interests, particularly oil exports. Sudan, the diplomat said, believes Juba is under internal pressure from officials aligned with Abu Dhabi, including proposals to build medical facilities along the border to treat RSF fighters.

Economic researcher Ahmed bin Omar estimates that “Sudan lost about $320 million as a result of the cessation of South Sudan’s oil exports during the war.” He argues that oil transit through Sudan has shifted from an economic asset to a political pressure tool, with Port Sudan able to threaten export shutdowns when tensions rise.

Sudanese oil fields under fire

Sudan’s own fields in West Kordofan—long central to the country’s domestic fuel supply—have suffered repeated disruptions. Although the army still controls the Heglig field, most surrounding towns are under RSF control. Ayman Maldo, an employee in Heglig, said production has dropped sharply as operating companies face soaring insurance and operational costs. “Production has declined significantly because the situation is volatile and the operating companies have raised operating costs,” Maldo explained. “Machinery costs jumped from $25,000 per day to double that during the war.”

Maldo confirmed that RSF drone attacks last month destroyed control equipment and critical devices in Heglig. Oil companies fear the strikes signal preparations by the RSF to seize the field and potentially push eastward toward Port Sudan’s remaining energy infrastructure. “Companies feel things are very worrying and that they are taking risks in an area that could turn into a hotbed of fighting at any time,” Maldo added.

Researcher Hani Othman said the army’s loss of Babnusa on 1 December strengthens concerns that the RSF is preparing an assault on Heglig, the military’s last major foothold in West Kordofan. He added that companies are not operating at full capacity due to uncertainty and the army’s inability to secure the area.

The RSF’s capture of the Balila field in October 2023—once producing 70,000 barrels per day before declining to 16,000 barrels due to neglect and instability—further weakened Sudan’s energy sector. Oil engineer Mohamed Abdo estimates Balila’s reserves at no less than 1.4 million barrels, though war has severely damaged the facilities that historically fed the Al-Jaili refinery in Khartoum North.

As domestic production dwindles, Sudan now imports approximately 90% of its fuel, a dramatic reversal from pre-war years when western fields supplied most local needs. Abdo added that the RSF’s push to seize Babnusa is directly linked to its proximity to Heglig—one of the last major assets still held by the government.