Repeated devastation, Sudan’s floods are getting worse

Aziz Mohamed is still dazed by the loss. Sitting listlessly in his relative’s home in Sudan’s capital, Khartoum, he left his whole life behind him. A farmer from a village along the west bank of the Nile in White Nile State, Aziz Mohamed had no time to collect any possessions or salvage any harvests from his flooded crops before departing for Khartoum. “We lost everything, even I don’t know where some of my neighbours ended up,” Mohamed told Ayin.

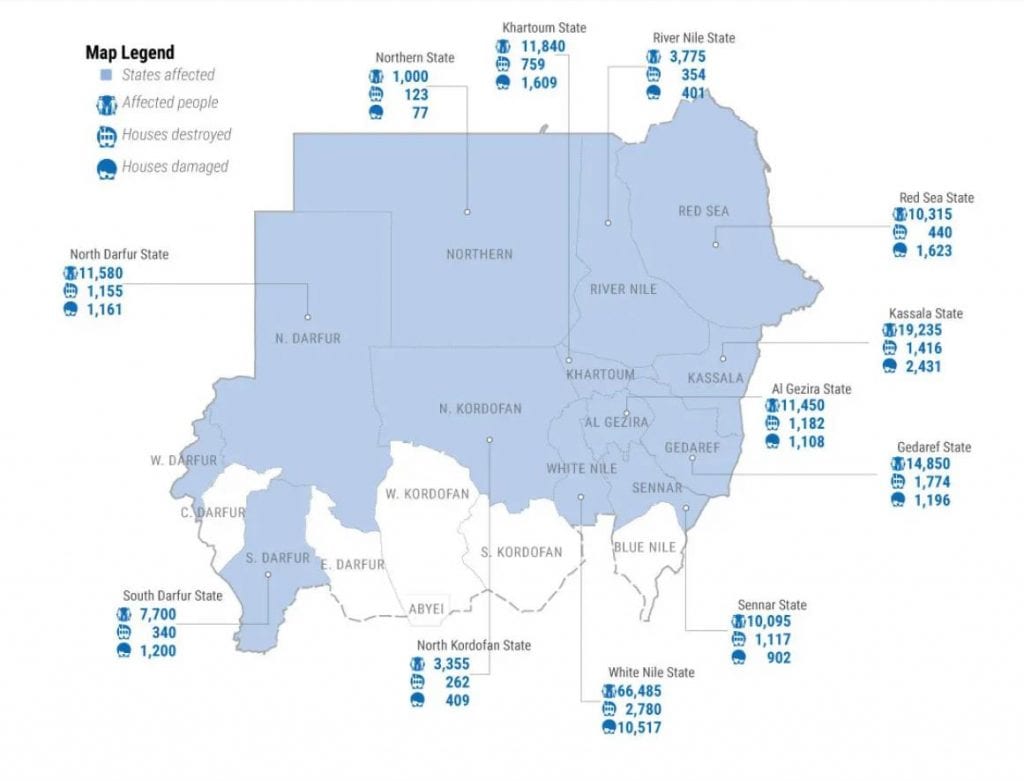

Since July, like previous years, heavy rainfall has led to devastating floods across the country. But this time it’s worse than previous years. Sudan is facing some of the heaviest rainfall and flooding since 2013 –taking place at a time when a collapsed economy and political transitions have curbed humanitarian reactions to the crisis. As of 2 September 2019, heavy rains and flash floods affected an estimated 346,300 people across 16 states, according to the government’s Humanitarian Aid Commission (HAC), surpassing the 222,200 affected last year. HAC has reported 78 flood-related deaths across the country, largely due to collapsed roofs and electrocution.

This year marks the highest recorded water level in the Nile due to rainfall in Sudan’s history, according to the Head of the Early Warning Unity at Sudan’s Meteorological Authority, Abulgassim Ibrahim Idriss. “We normally have 120 mm of rainfall for this season but you can imagine we had 155 mm of rainfall in just one night in the southern part of Khartoum,” Ibrahim told Ayin.

White Nile awash

White Nile State has had nearly 3 – 4 times the number of people affected by the floods in comparison to the rest of the country. The floods, according to the UN coordination body OCHA, have affected over 66,000 people in White Nile State alone. Many have lost their homes completely with 13,300 homes either damaged or destroyed –this represents nearly 20 percent of all homes damaged by floods across the country.

Ali Musa comes from a village near Al Douaim town in White Nile State and says around 35 villages south of Al Douaim were completely destroyed in the floods. “There is not anyone left in these areas, most of the crops were affected so the area is largely abandoned,” he told Ayin. Government support to the area has been minimal, Musa added, saying most people in White Nile rely on relatives and a handful of non-governmental organisations to cope.

So far the government has not visited one of the worst affected areas in White Nile, the Umm Ramat county, says resident Osman Abu Sammya who was forced to abandon his village home in Umm Ramat. In the early days of the flood, Abu Sammya said, road access to their village was completely cut off, allowing only aid deliveries by air. “The situation is very critical, people are now living in the open, exposed to rain and even complain about bites from scorpions and mosquitoes,” Abu Sammya told Ayin. People are now drinking the flood water out of desperation, he added.

White Nile State also hosts the second-largest refugee population in the country with an estimated 235,539 South Sudanese refugees. UN and aid agencies have not been able to access certain flooded refugee camps in the Al Salam area, OCHA reports, estimating that over 900 refugee households have lost their shelters in the heavy rains.

With homes and shelters destroyed, non-food items are some of the key needs for humanitarian assistance, according to OCHA. But as of 10 September, humanitarian funding only reached 33 percent of the amount requested. The sector with the largest needs, non-food items, has only reached a paltry 1 percent of the funding target. To date, humanitarian actors have only been able to reach 34 percent of those in need in Sudan, OCHA reported.

Aziz Mohamed saw his home and possessions literally float away from him. But what makes the situation unbearable, he says, is not losing these past possessions but the uncertain future after his crops and livestock were depleted in the floods. “We have gone from wealth to poverty in a few hours.”

Heavy rains, light food

August is typically when rains hit hardest in Sudan, it is also the peak of the lean season where food access remains seasonally low. The combination could prove disastrous for some of the more marginalized regions of the country. “We have had above-normal rainfall levels this year but it is not good for agriculture since the farms are flooded,” Ibrahim from Sudan’s Meteorological Authority said. “You can’t have the whole season’s rainfall occurring in one month as we have experienced, it’s not good for farmers or anyone.”

Food insecurity has been exasperated further by the ongoing economic challenges within Sudan as well as the recent flooding. The Sudan Central Bureau of Statistics reports that inflation rates increased from 48% in June to 52% in July. The depreciated currency along with shortages in fuel and grains are driving high food prices across the country. Staple grains such as sorghum remain on average 55 percent higher than last year, according to the Famine Early Warning System (FEWS), a US-funded food security-monitoring organisation. Livestock prices have also spiked by 150 percent since last year due to the floods and economic hardship, FEWS reported.

The sharp spike in food prices and inaccessibility to flood-filled markets is proving particularly challenging in Blue Nile State, says Ishraga Khamis from the Sudan Relief and Rehabilitation Association (SRRA). “Many livestock have died and crops washed away in the floods,” Khamis said, “We fear this could cause famine in some areas in the coming months.” According to the South Kordofan / Blue Nile Coordination Unit, an organisation that monitors humanitarian conditions in the two areas, heavy rains along the Yabus River have destroyed nearly all (95 percent) of harvests. Few humanitarian actors are on the ground, Khamis told Ayin. “Even displacement camps managed by the UN are struggling with people sheltering in schools without any humanitarian response taking place,” she said.

Foreboding future

The UN predicts heavy rains are set to continue and worsen floods especially in River Nile, Red Sea, Al Jazeera, North Kordofan, North Darfur, Khartoum and White Nile states. The opposition umbrella group, the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC), have demanded that the government declare Sudan a natural disaster zone, Radio Dabanga reported. But the political transitional period –where a newly formed government only emerged last week—is poorly prepared to contend with the disaster. Newly appointed Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok told Reuters in an interview that the floods needed immediate government intervention with solutions to ensure citizens are protected from repeated occurrences. But so far, says Ghazi Elrayah, a volunteer with the Khartoum-based charity Nafeer, the response from authorities has remained weak. “It hasn’t changed this year, we do the emergency relief for this country –what we are doing is not a permanent solution.” But according to one UN worker, they are already seeing improvements in terms of humanitarian access once the new government was established. “For instance, in parts of White Nile there were some access issues which have now been resolved,” the UN official told Ayin. “We will see an increase in the number of people assisted in the coming days.”

Further assistance and long-term solutions for Sudan’s cyclical floods are long overdue, especially since climate change will likely increase the rate of floods in the country. “I think climate change is there,” Ibrahim said. “The cycles of floods are increasing. In the past, there was some time between incidents but in recent years we are always expecting floods on a yearly basis.”

Given this scenario, Aziz Mohamed is unsure when he will ever be able to return to his home village and escape the hustle and bustle of city life in Khartoum. “This place [Khartoum] is not my home,” he said, “but with my home flooded, it may have to be.”