The struggle for Sudanese women’s rights: gains at home, losses abroad

Although divorced from a past, abusive husband, Sahar* still felt trapped. Until recently, regulations would prohibit mothers from travelling without legal consent from a male guardian. “Sudanese laws are highly unfair to mothers; it restricts us in many ways. My ex-husband got remarried and doesn’t care for our children, and yet threatens to take them away if I was to get married or travel seeking a better living,” Sahar told Ayin.

But last month proved a boon to Sudanese women’s rights in terms of national legal reforms. In July, the Sovereign Council ratified several legal amendments that included criminalizing Female-Genital Mutilation (FGM) and removing a regulation adopted by the immigration and customs authorities that prohibited women from travelling alone with their children without written consent from a male guardian of the father’s family.

“Single mothers waited for a long time for this move, now we can finally travel and seek a new beginning,” Sahar added, “I hope all of the family laws get reviewed and changed by the Justice Ministry.”

Sudanese lawyer Mohamed Osman from the global Human Rights monitoring body, Human Rights Watch (HRW), called the amendments a step in the right direction; “They’re among the main demands for political transformation to move from the legacy of abuse sanctioned by the law and create a better legal system that goes along with international laws and the constitution of declaration.” To Osman, the legal reforms challenge one of the main principles affecting several Sudanese laws –the concept of women not being equal to men.

But there are many more legal reforms needed, both locally and abroad, to improve Sudanese women’s standing in society, says Ihsan Fagiri, the Head of No to Women Oppression, a Sudan-based feminist advocacy initiative. One key accord, Fagiri says, is the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). The convention is often described as an international bill of rights for women, adopted by the United Nations in 1979 and ratified by 189 states.

Shortly after announcing the law amendments on 17 July, Sudan voted against the draft resolution at the 28th meeting of the 44th Session of Human Rights Council in Geneva.

Sudan’s deputy ambassador in Geneva, Osman Abufatima Adam, said his country

had taken major steps in improving women rights and women participation in politics, yet rejected the draft resolution due to “cultural differences” regarding sexual and reproductive rights.

Amira Osman, the Deputy Head of No to Women Oppression says that ratifying CEDAW is up to the Legislative Council, adding that the transitional government lacks the courage to discuss the agreement or take a step forward. Even worse, Osman said, Sudan’s international representatives largely emanate from the former ruling party, the National Congress Party (NCP) who has no interest in improving Sudanese women’s standing. “Most of the representatives of Sudan remained the same since the era of the NCP, this move was expected,” she said.

Society and Transformation

The three decades with the National Congress Party (NCP) in power had converted many elements in Sudanese society to oppose attempts to support women’s rights. Some communities are not embracing the changes proposed by the revolution and the transitional government – even breaking laws to continue outlawed practices such as FGM.

The legacy of the former government has built opposition from certain groups to these legal reforms, says Mohamed Osman. “For people to truly embrace the law amendments, the Legislative Council along with committees such as transitional justice committee, human rights, and legal reform committee should be formed to lead the transformation”, he says. Fagiri, however, is confident society is ready for change. “Sudanese society is very different from Sudanese politicians who push women aside from decision-making positions and turn their heads away from their rightful demands”, she told Ayin.

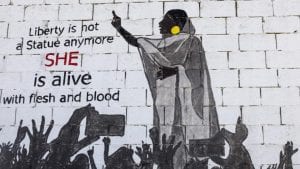

“The revolution had sparked a change in the level of awareness among people –especially women as women were actively participating and leading in the revolution,” she adds.

Lack of Women Representation in Politics

Despite Sudanese women’s contribution to the revolution, there appears little to show in the aftermath of the former regime. The law amendments ratification coincided with the first list of appointed governors state governors. The list contained 13 names –all male, not a single female candidate was appointed much to the ire of women rights advocates and female politicians.

Information Minister Faisal Mohamed Salih responded to the criticism by claiming that “the political parties” did not represent any female candidates for governor positions. In response, the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC) issued a statement denying the allegation. “The statement given by the Minister of Information about not nominating female candidates is not true; four states have nominated women presented by their political parties for governor positions,” they announced. The group suggested dedicating half of state government positions to women to counterbalance the lack of women representation in the state governorships.

Satie Alhaj from the FFC told Ayin that they agreed on a list of 90 candidates for the 18 states that included women, “The female nominees didn’t receive enough votes during the elections from the small list. FFC did not aim to exclude women, the final list was selected based on the votes”.

“Women have been pushed aside from decision making positions despite their sacrifice,” Ihsan said. “We started an initiative to demand our rights in political participation, and condemn the recent developments from the political bodies.” The initiative was named “Hagna Kamil, Ma binjamil – “Our Rights in Full, No Compromising”.

Modern “Hareem”

Eventually, two female governors were appointed but this did not placate Ihsan and the 40 different women’s rights groups who protested the lack of female appointments through a memo shared with Prime Minister Abdullah Hamdok. The premier acknowledged receiving the memo and showed his support via social media. This took place a week after meeting 12 freshly appointment ambassadors—all men.

Eventually, two female governors were appointed but this did not placate Ihsan and the 40 different women’s rights groups who protested the lack of female appointments through a memo shared with Prime Minister Abdullah Hamdok. The premier acknowledged receiving the memo and showed his support via social media. This took place a week after meeting 12 freshly appointment ambassadors—all men.

As the negligence of women in decision making continues, feminists and women rights advocates are relating the issue less to authorities and more to a social mentality and archaic belief system that women are, simply put, beneath men. Ihsan says Sudanese women are still viewed in a traditional image, an image that cannot fathom women as politicians. “They are basically telling us to stay in our place, the Hareem yard, away from men.” The “Hareem” Ihsan refers to is the traditional section of the house devoted to women, separated from the decision-makers in the house, the men.

Attitudinal change and more legal reform are required before Sudanese women are able to hold office on an equal playing field with men. “Women cannot participate in politics freely and efficiently unless they are treated as politicians first,” writes feminist blogger, Yosra Fuad. The Personal Status Law in Sudan, for example, still allows male relatives control over their female counterparts in almost areas of life, including education, work, marriage and divorce. Only the lucky few women who marry progressive male guardians or have fought long battles to free themselves from their social shackles are able to pursue political careers. Issues such as male-guardianship, however, are not being discussed in politics –partly due to a lack of awareness and since lobbying for such social change is politically unpopular. Fuad believes the way forward is to tackle the issue from the root. “Without eliminating the male-guardianship system, women involvement in politics will be limited to those with privilege,” adding that politics will remain an all-men club with extremely limited female participation.

Despite these setbacks, a sense of change is, albeit gradually, emerging in terms of women’s rights in Sudan at least for mothers like Sahar who fought for so long; “I will finally be able to give my children the life they deserve,” Sahar said, “and live somewhere safe without being constantly afraid of their father or his family coming after us.”

* Name changed upon request for security purposes.