How much is a successful rebellion worth in Sudan?

3 July 2024

Since independence, Sudan has faced repeated internal conflicts where armed groups use violence to force the central government to provide more political representation. Since the government initially supported and brought the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) to Khartoum to counterbalance Sudan’s rebel groups, the current conflict is a continuation and outcome of these conflicts. After the current war concludes, whatever government forms will very likely continue to face challenges from redistributive rebel groups. The key ideological justification of most Sudanese rebels is that political representation won through violence will benefit their ethnic constituencies. Despite the tremendous costs of these wars in blood and treasure, the returns to victory for ethnic constituencies are surprisingly small. This article reviews a recent paper in the British Journal of Political Science that finds the benefits of victory for rebel constituencies are modest, on the order of a few percentage points of productivity, making it difficult to justify the costs of conflict.

One Friday in 2000, activists in Khartoum stood outside mosques across the city, distributing photocopies of their radical political treaties, titled “The Black Book: Imbalance of Power and Wealth in Sudan”. Each copy had been hand-photocopied in order to avoid government censorship. “The Black Book:” was an indictment of the distribution of power and income in Sudan between the poorer periphery regions, like Sudan, and the richer regions along the Nile. It tallies the number of senior officials to show that they disproportionately come from Sudan’s wealthier riverine regions. It claims that regions like Darfur and Kordofan are poor because Khartoum’s politicians refuse to direct state investment there, preferring the metropole for new universities, irrigation projects, dams, and hospitals. Some of these activists went on to start a new armed political group, the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) which fought in several civil wars and eventually forced the government to sign power-sharing deals with it. Today, Sudan’s finance minister, Jibril Ibrahim, is a leader of the JEM. These redistribution-minded armed groups have achieved their political objectives, but new research suggests the gains are much smaller than expected.

The Black Book inspired one armed group, JEM, but similar ideas motivated several armed groups in Sudan, including the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) and the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA). Even Western observers writing on Sudan sometimes repeat the claim that regional inequality is primarily a result of government policy, as in this Rift Valley Institute publication. Over the past 20 years, these armed groups have periodically engaged in attacks on Sudan’s armed forces or infrastructure, which triggered cycles of retaliation leading to several civil wars, most notably the 2003 Darfur war. The resulting civil wars were costly, but they did force some administrations to include leaders from the periphery, particularly members of the rebel groups themselves. Redistribution is not the only purpose of these armed groups, they also both defend and extort their host communities, but it is a central ideological justification.

The rebel groups that subscribe to the Black Book’s understanding of poverty and underdevelopment have what aid workers would call a theory of change—a model with sequential steps to achieve their goal (in this case, regional economic equality). The first step is to use violence to demand positions in the federal and state administration. The second is to use those positions to change the distribution of investment and economic policies. The third is that those new policies will improve the welfare of people in the periphery.

Like any theory of change, it relies on assumptions about how the world works. One assumption is that violence will cause the state to make concessions. The Darfur Peace Agreement (2006) and the Juba Peace Agreement (2019) proved, to some extent, that violence worked. The JEM and other rebel groups have entered into power-sharing deals that place their leadership in cabinet positions and provincial governments. These agreements have given some rebel leaders significant influence. For example, Sudan’s current minister of finance, Jibril Ibrahim, is a JEM leader. However, the state would only make concessions after long and costly wars, which severely damaged the welfare of the periphery. To make the theory of change work, the redistributive benefits for citizens of the periphery must outweigh the considerable costs of conflict.

The redistributive theory of change also assumes that the Sudanese government can change the fortunes of villagers in the periphery. A report from the Rift Valley Institute found that the Juba Peace Agreement of 2020 had little effect on the budget allocated to regional governments. There may be confounding factors that explain the agreement’s failures. The Juba Peace Agreement’s implementation coincided with a major state financial crisis in 2018.

The question of whether rebel redistribution works is intractable within Sudan. Any agreement will face unique situational challenges that could explain its failure. Poor data also hinders any statistical work. Data on family budgets and poverty by region is poor and infrequently updated, and as of 2023, the latest budget survey was in 2014.

The empirics

We can, however, look at a broader sample of rebel power-sharing deals and investigate the average effect on productivity in the regions affected. A paper recently published by Felix Haas and Martin Ottman in the British Journal of Political Science measures the size of the rebel redistribution effect for post-conflict power-sharing deals in several African states, including Sudan. Effectively, they measure the change in economic activity, proxied by satellite data, due to winning a civil war and putting a coethnic in the cabinet.

Haas and Ottman decompose the economic effect of winning a rebellion into two distinct effects. They define winning as forcing the government to sign a deal that guarantees state jobs for some rebel group members, including one or more cabinet seats in exchange for the cessation of violence. These three effects are:

- The end of violence, brings obvious and significant benefits to both the rebelling ethnic groups and to the ruling ethnic groups and others caught in the crossfire.

- Former rebels in these new government positions can modify the policies that they believe led to poverty in the areas they represent.

Haas and Ottman are concerned with this third effect, the “rebel redistribution effect”. According to the rebels’ theory of change, when power-sharing agreements are created, there should be an increase in prosperity for the regions occupied by ethnic groups represented by rebel groups. Moreover, this increase in prosperity should be over and above any increase enjoyed by the leader’s ethnic group, which was always represented, and the unrepresented groups who do not receive a cabinet seat. In other words, districts with many ethnic group members who receive a cabinet seat should get a larger bump from peace deals than just the reduction in violence.

Hass & Ottman (henceforth H&O) construct a dataset of power-sharing deals that reach the cabinet level in African countries, including the 2006 Darfur Peace Agreement (DPA), a 1994 deal in Mali, a 1999 deal in Niger, Unita’s 2003 deal in Angola, 2004 deal in Liberia and the DRC, and 2006 deal in the Ivory Coast.

They record the primary ethnic groups that each group represents and use data on their settlement locations to construct a map of the newly-included group’s territory. For example, Figure 1 gives the areas of settlement map for the Beja people of Northern Sudan (via GeoEPR) and Figure 2 gives the map of included groups throughout Africa (Haas and Ottman, 2019).

The coast of the United Arab Emirates viewed from space at night. The well-lit roads and built-up areas can be clearly distinguished from the countryside. (NASA)

The coast of the United Arab Emirates viewed from space at night. The well-lit roads and built-up areas can be clearly distinguished from the countryside. (NASA)

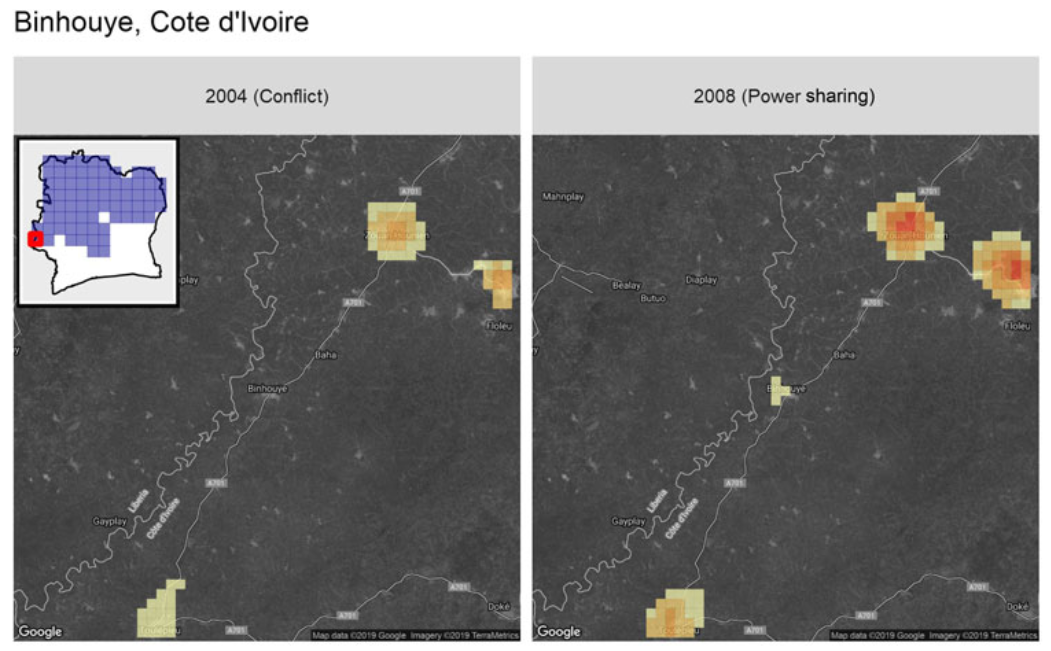

A map that plots nighttime light emissions in rebel ethnic constituencies in the Ivory Coast. A darker colour indicates higher nighttime light emissions. The shaded blue area on the inset is a rebel ethnic constituency area. (Hass & Ottman)

A map that plots nighttime light emissions in rebel ethnic constituencies in the Ivory Coast. A darker colour indicates higher nighttime light emissions. The shaded blue area on the inset is a rebel ethnic constituency area. (Hass & Ottman)

H&O uses nightlight intensity data from satellite surveillance in place of government-collected data on income. As regions become more economically developed, they consume more electricity and produce more light. A portion of that light escapes into the night sky, where global satellites regularly scan the ground. H&O links the ethnicity-region data to annual data on how much light is detected and decomposes into 55 km by 55 km grids.

With data on which regions have a coethnic in the cabinet and their night light, H&O can assess the effect of each peace deal. They use what in econometrics is called a “difference-in-differences” design to measure the relative economic changes in each region. For example, in a normal year, the Beja-majority regions and riverine Arab regions should move together in their productivity. In 2006, when a new power-sharing deal included the Beja, their output should jump relative to the other populations, to control population movement and reduce violence levels. Intuitively, both groups benefit from the reduction in fighting and any stability gains from peace, but only the Beja have a new connection in the highest echelons of power.

They find that political inclusion does have an effect, but a small one—there is just a.7 percent increase in nightlights for victorious rebel groups over others. Haas and Ottman use past data on the GDP nightlight to estimate that a .7 percent increase in nightlights should create a .9 percent increase in GDP. A person living on 2 dollars a day can expect an average benefit of just under 2 cents. For the typical person in an African rebel constituency, winning a civil war is better than losing, but only barely. Even worse, they find that the effect decreases over time, which suggests that victory results in short-term rent distributions and not the hope for growth explosion.

There are some limitations to Haas and Ottoman’s approach. First, they measure the average effect by area without taking population density into account. It is plausible that the impact of such deals is larger in population centres like Juba due to urban bias, which would lead to underestimation. Secondly, the drawing of the ethnic zones is crude, misses many ethnic groups (see Figure 2), and includes some very sparsely populated tiles, e.g., northern Red Sea State. To the extent that the sample includes regions that are uninhabited or contain the governing ethnic group, the effect size is larger than represented. Nonetheless, it’s difficult to argue that the effect is large enough to compensate for the damage of the conflict based on these results.

Why is rebel redistribution so paltry?

One plausible explanation is that rebels are too weak in their control of the government, and therefore fail to pass policies that would benefit their ethnic groups. The problem with this explanation is that the effect of favouritism from the head of state is substantively similar in size. In “Regional Favouritism,” Hodler and Raschky use a very similar design to measure the effect of being from the same region as the head of state. They estimate the gains at 1.4% of GDP per capita, just 50% higher than H&O’s estimate for power-sharing deals. This suggests that paltry redistribution is not unique to rebel politics.

We should also be sceptical of any explanations that point to unique Sudanese events or cultural factors, like the rejection of the Darfur Peace Agreement by the Justice and Equality Movement and Abdul Wahid Al-Nur (Washington Post, 2006). The study reported the average effect on productivity across deals in 7 distinct countries, which would average out unusually bad performances. Underperformance is the rule, not the exception.

Why rebel redistribution may have little effect

Firstly, African states tend to be weak, particularly shortly after emerging from conflicts. On the World Bank’s government effectiveness rankings for 2022, Sudan came in 185th place, narrowly beating Eritrea, Syria, and Somalia (before the most recent war). Furthermore, the Sudanese government taxes only about 10 percent of its GDP (World Bank, 2024), giving it a small budget with which to implement change.

Secondly, redistributing income from richer to poorer regions is a difficult task. The wealthier region must be taxed more, creating distortions from tax avoidance as businesses avoid paying taxes when they no longer see the benefit in local services. More value is lost in multiple layers of bureaucracy moving funds around, particularly in a high-corruption context. Local governments may misallocate the revenue due to limited capacity. Once funds reach poorer regions, they may not stay there as local spending flows out through imported goods and services. Finally, poorer regions are less integrated into the national and global economies, limiting the return on investment.

These problems plague any redistributive scheme but are particularly severe in a post-conflict setting. For example, after the Juba Peace Agreement, requirements for the regional governments to hire former members of rebel groups created challenges to simply meeting payroll—expanding service provision was far beyond their means.

Thirdly, there are incentive problems in post-conflict negotiations. After the war, there will be limited resources allocated to the armed group, which can either go to public services or jobs, and demobilisation payments for the armed group members. After years of conflict, the armed group negotiators have different incentives from the ideological activists who wrote the Black Book. Running an armed group requires sustained effort and resources from its officers, fighters, and financiers, who will expect to receive value from the agreement. Policies that benefit everyone in a region, like irrigation investments, power lines, and schools, tend to be an inefficient way to pay back the individuals who fought. Even in the most militaristic societies, only a small fraction of individuals are professional soldiers, usually below one in thirty. Because fighters are only one-thirtieth of the population, the value kept within the force is thirty times more efficient than compensation disbursed through public goods like schools and infrastructure.

If a warlord insists on broad redistribution instead of cash for troops, those fighters can leave for another army. Armed groups often collapse as fighters split off into new factions, hence the extended acronyms like SLA-N-MN for the Sudan Liberation Army—North—Minni Minnawi faction. This creates a powerful disciplining force for armed groups to maximise their private rewards. Even if state policies can develop the periphery after wars, armed groups are likely to capture most of the allocation.

None of these factors are likely to change in the foreseeable future. The very government buildings that could tax Sudan’s centre to provide public goods in the periphery lie looted and in ruin. Any future government will have to build a state almost from scratch.

The Sudanese people and the international community should be sceptical of rebel Robin Hoods. Their theory of change is fundamentally flawed because the prize in contention, state power, is not worth fighting over.