South Sudan’s RSF mercenaries, fears of more to come

22 March 2024

The South Sudan National Army, also known as the South Sudan People’s Defense Force, (SSPDF) has distanced itself from any links or connection to the 14 South Sudanese mercenaries captured by the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF), allegedly fighting alongside the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) last week during the recapture of the Radio and Television Corporation headquarters, a location the RSF controlled since the onset of the war.

The SSPDF spokesperson told Ayin Media in the capital, Juba, that the army has nothing to do with the mercenaries.

“No. Those mercenaries are not members of SSPDF and are not connected in any way. They were individual South Sudanese who fought on their own as mercenaries,” said Major Gen. Lul Ruai, the SSPDF spokesperson.

A UN Panel of Experts report leaked in mid-February stressed the South Sudan government’s lack of knowledge of these mercenary activities in their neighbouring country. The government also denies any involvement in allegations of certain army personnel smuggling oil to support the RSF in Darfur.

For nearly a year, a war of political and economic dominance has taken place in Sudan, pitting the army against the paramilitary RSF, displacing over 7 million people and triggering severe food shortages across the country. Multiple regional negotiation efforts have failed to reach any compromise, triggering fears Sudan’s war will gradually drag regional actors into the fray.

The arrest of the 14 South Sudanese mercenaries affirms the army’s claim of RSF’s fighting force composition, as top military generals have always accused the RSF of recruiting fighters from neighbouring countries. According to the Sudan Tribune, the captured group possessed expertise in operating heavy artillery and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs).

Maj. Gen. William Manyang Mayak, the 4th Infantry Division Commander in Unity State, had said the army had credible information about the RSF’s collaboration with South Sudanese rebels led by General Stephen Buay Rolnyang.

Gen Manyang claimed that the RSF and General Buay’s forces were planning attacks on Fulla and Heglig, followed by the South Sudanese border and its oilfields, citing sources within Sudan who helped the army gather information about their activities.

General Buay, a former commander of the 4th Infantry Division, defected in 2021 following years of detention under suspicion of collaborating with the rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Army – In Opposition (SPLA-IO).

Need-based neutrality

South Sudan’s government has been careful to maintain a neutral stance towards both warring parties to ensure their critical crude oil, constituting 95% of the country’s income, is refined in Sudan.

“Nothing, it won’t change anything,” South Sudan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs acting spokesperson, Denis Dumo, told Ayin when asked whether the capture of South Sudanese mercenaries would affect South Sudan’s relationship with its northern neighbour.

“Our neutral stand remains the same. As our President Salva Kiir stated, peace in Sudan means peace in South Sudan. It is our hope that soon, the parties to the conflict will sit down and resolve their differences.”

According to Addis Ababa-based Horn of Africa security analyst Selam Tadesse Demissie, South Sudan must maintain neutrality towards the warring sides to avoid making the oilfield a target.

“Protecting the oilfield should be the focus of regional and international conflict resolution efforts, with both sides in Sudan being held strictly responsible. In parallel, international financial assistance is needed to address the dire humanitarian situation in South Sudan,” Selam wrote.

Oil production problems

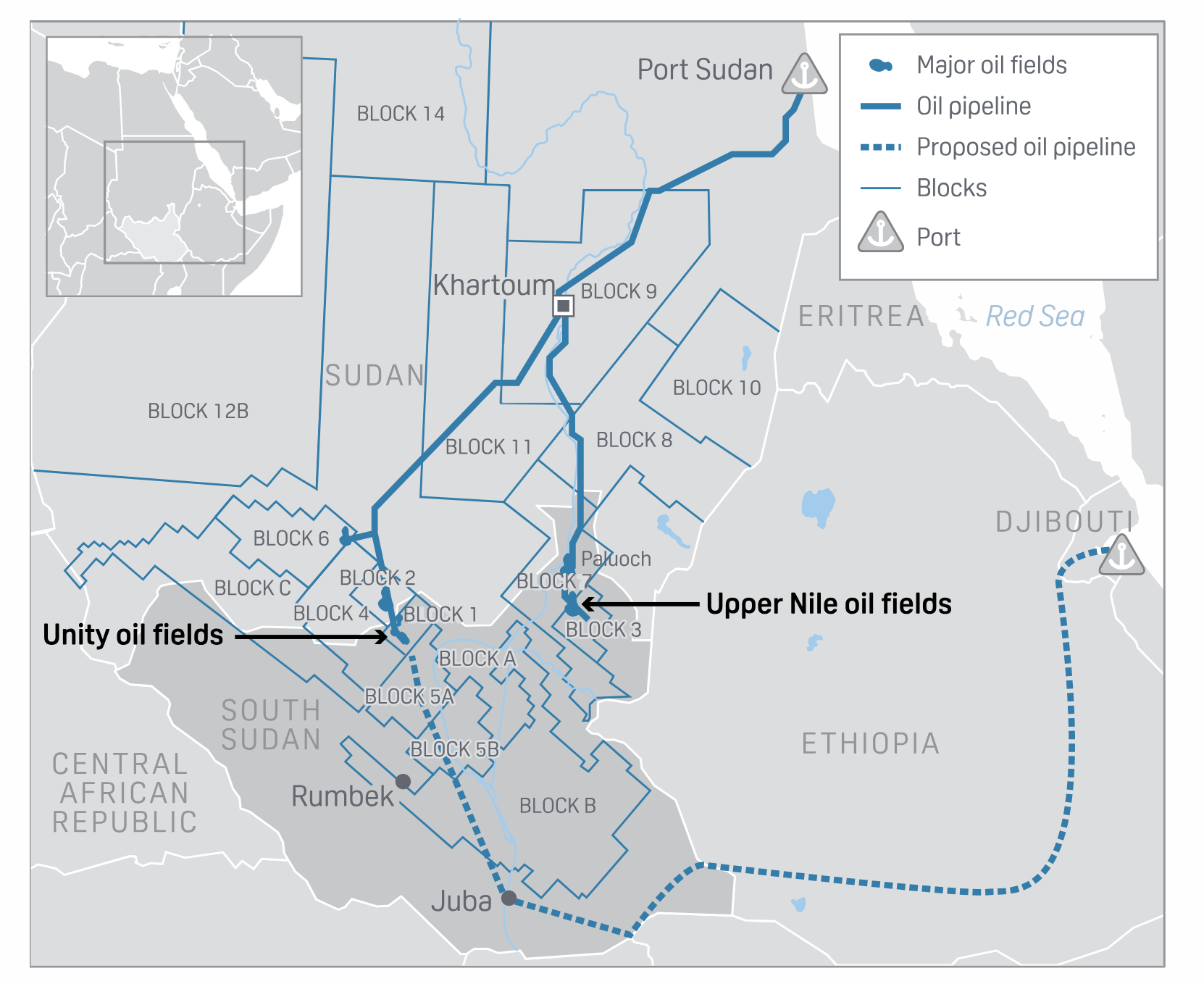

A major rupture has occurred in a pipeline, Sudan War Monitor reported, that carries crude oil from South Sudan through Sudanese territory to Port Sudan, prompting the Sudanese oil minister to inform Chinese and Malaysian production partners that Sudan cannot meet its obligations to deliver crude oil. The rupture occurred due to a clog in an underground pipeline in territory controlled by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in northern White Nile State, at a village about 20 km south of the town of al-Giteina, near the frontline with the Sudan Armed Forces.

Due to military operations in the area, pump stations operated by the state-owned Bashayer Pipeline Company (BAPCO) ran out of diesel, causing a “gelling incident” (clogging) that led to a major rupture according to a letter dated 16 March from Sudan’s Minister of Energy and Petroleum, Mohieldin Naim Mohamed Said. Oil tankers due for loading in Port Sudan in late February could not do so, and the last loading was in mid-February.

If it cannot be repaired, the rupture threatens a key source of revenue for the governments of both countries, particularly for South Sudan, which has failed to develop alternative revenue sources since its independence from Sudan in 2011.

The incident began on 10 February and was largely hidden from the public, according to the resource economy trade think tank, S&P Global Commodity Insights.

Engineers in the oil fields of West Kordofan also confirmed cases of sabotage two weeks ago in the Dafra oil field, near the Heglig oil field, situated on the border between Sudan and South Sudan.

Earlier this month, Sudan’s Minister of Energy and Oil, Muhyiddin Naeem Saeed, said the reconstruction of the oil infrastructure destroyed during the current war will cost at least $5 billion.

Saeed told the official Sudan News Agency (SUNA) that about 210,000 barrels of crude oil had been lost from the previous sabotage of the storage facility at the Khartoum refinery, which used to provide about 40% of Sudan’s needs. The decline in oil production throughout this period has led to the loss of about seven million barrels of crude oil.

More mercenaries

But the consequences of Sudan’s southern neighbour’s inability to export oil may prove even more catastrophic. The S&P Global analysis implies that with limited to no oil revenue, the South Sudan government will eventually be unable to pay its soldiers and may trigger more mercenary activities similar to what is reported in Omdurman.

“Without immediate intervention, this situation could spell doom for the South Sudanese government,” South Sudan’s Minister of Information said at a press conference on 27 February. “Oil revenue is our primary source of income.”

However, the rupture only affects flows on one of two branches of the pipeline system, namely, the Petrodar Pipeline, which brings oil from Upper Nile State in South Sudan. It’s unclear so far if flows from oilfields in Unity State in South Sudan will be affected.

Even if the pipeline can be repaired, the oil industry in the two countries faces other existential threats, including Houthi attacks on shipping in the Red Sea and a lack of interest by companies to invest in the sector, given the risk of a cut-off at any time.