Sudan’s visit to Russia may yield more losses than gains

1 March 2022

As Russia invades neighbouring Ukraine, Sudan’s top military leadership recently visited the country in what analysts claim is another attempt to attain foreign support and hold onto power.

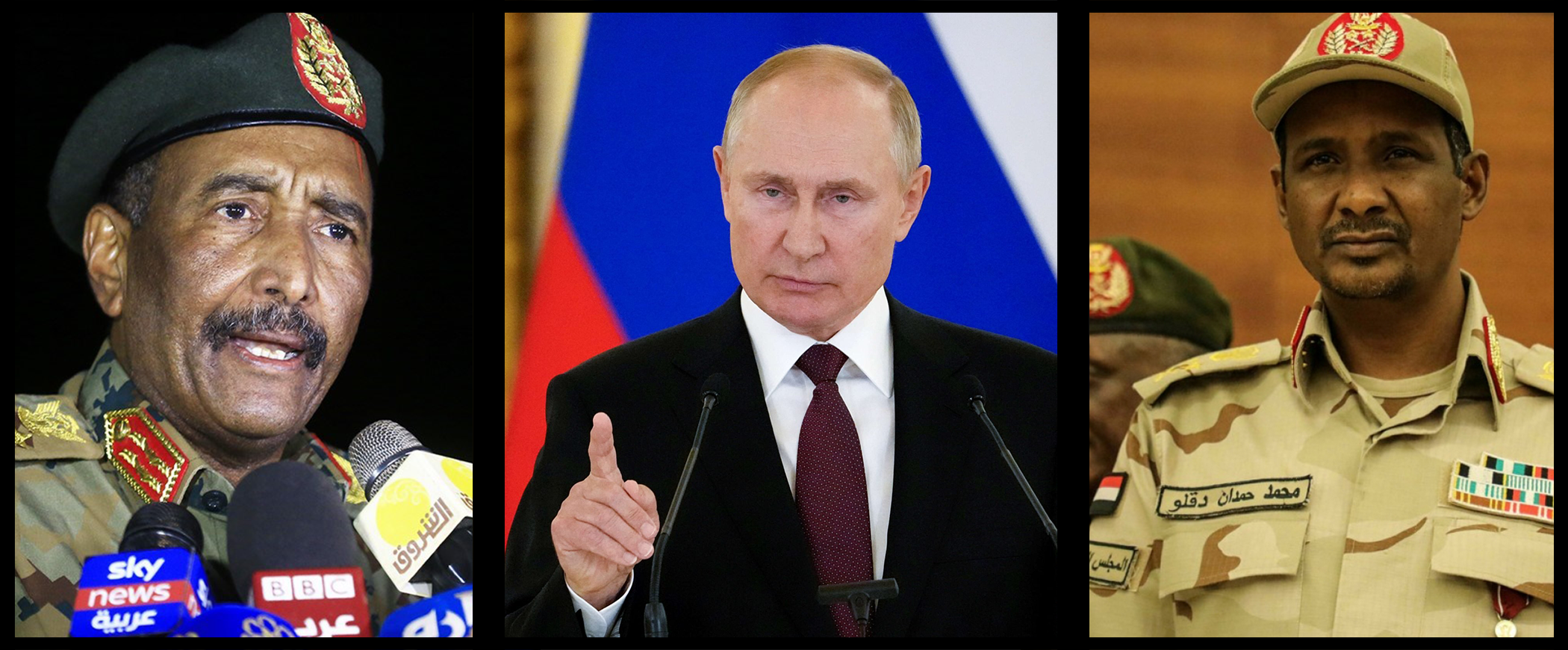

Last Wednesday, Vice-President of the Sovereign Council, and the Commander of the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), Lt.-Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (known as “Himmedti”) travelled to Moscow at the invitation of the Russian government. This meeting follows a prior engagement with Sovereign Council Head and leader of the military coup on 25 October, Lt.-Gen. Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan, with Russian President Vladimir Putin in October 2019.

While the exact reasons for the meeting remain unclear, Sudan’s state news agency claims Himmedti met with Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak to discuss ways to boost bilateral relations.

This is not the first time Sudan’s military has reached out to Russia to maintain power, however illegitimate. In May 2019, immediately after the fall of the Bashir regime, the military wing of the former transitional government developed two cooperation agreements with Russia. The two agreements came at a time when the Sudanese were holding a sit-in directly in front of the army’s general headquarters in Khartoum’s centre to demand civilian rule. The two agreements, according to analysts, reflected the army leaders’ attempt to retain power “in the post-Bashir phase.”

Grasping at straws

Perhaps in a desperate bid to cling on to power, says Cameron Hudson, former Chief of Staff for the U.S. Special Envoy to Sudan, Himmedti hopes to leverage fiscal support. According to Hudson, non-public assessments indicate that Sudan has 1 – 3 months of remaining reserves for imports, “which means things like wheat, diesel, and medicine will be in short supply and become much more expensive.”

Many in the pro-democracy expect the dire economic situation will ensure the anti-coup protests gain further momentum as the Sudanese citizenry grapple with hyperinflation. Ibrahim Hassan, 30, a protestor against the coup told Ayin during last Sunday’s demonstrations, that they expect a stronger turnout going forward due to the severe economic crisis.

“Of course, people will take to the streets – what else can they do?” says Fatima Abdelrahman, 24, another frequent pro-democracy demonstrator. “We do not have anything in our homes, our shelves are bare, the streets are the only thing left.”

Russia may be the military leader’s last hope for financial support after friends in the Gulf states did not yield new pledges, Hudson said. But chances Russia has surplus cash to support Sudan’s failing economy seem far-fetched given the country’s current war with Ukraine.

Worse still for the coup leaders, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine may induce a spike in bread prices –-the original instigator to Sudan’s civilian-led protests that helped topple former president Omar al-Bashir in April 2019. Russia is the world’s top wheat exporter and Ukraine the fourth, according to estimates by the US Department of Agriculture, the two countries represent 30% of the world’s wheat exports. David Beasley, the World Food Programme’s executive director, said the Ukraine-Russia area provides half the agency’s grains.

Even Russia’s ability to provide diplomatic support to Sudan’s generals may be waning due to the Ukrainian invasion. In early November, the Russian delegation to the UN Security Council opposed attempts by western countries to condemn the military coup in Sudan and called on parties for dialogue and confidence-building. Himmedti reportedly thanked Novak in their ongoing meeting in Moscow for his government’s support in international forums, especially at the UN Security Council.

But this support may dissipate if diplomats in New York are successful in challenging Russia’s right to a permanent seat at the UN security council. The bid to remove Russia’s permanent seat is based on the grounds that Russia took the chair from the defunct Soviet Union in 1991 without proper authorisation.

Whatever the exact reason for Sudan to visit Russia, the timing could not have been worse.

Analysts say Himmedti’s ill-timed visit will inevitably curb chances of rekindling U.S. support, despite Sudan hiring Washington lobbyists recently to reset relations with the West. The visit comes as the European Union (EU) and the United States imposed heavy economic sanctions against Russia after the Ukraine invasion. On Sunday, ambassadors of the EU and Troika countries asked the Sudanese government for its official position regarding the Ukraine invasion and called on Sudan to publicly condemn the attacks. They also questioned the Deputy Sovereign Council leader’s visit to Moscow in conjunction with the Russian attacks and called on Khartoum not to support Russia’s decision.

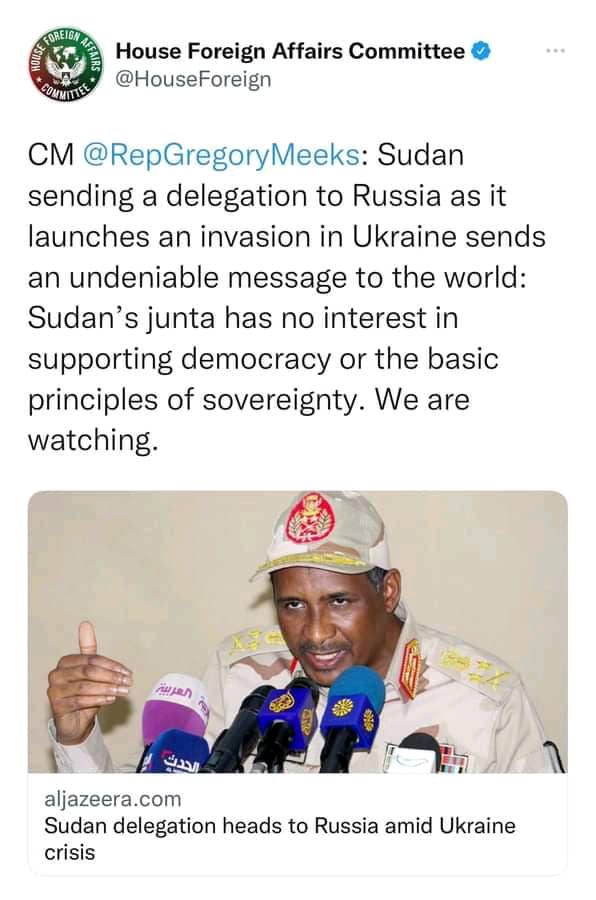

Reacting to the visit, US Congressman Rep. Gregory Meeks said that “sending a delegation to Russia as it launches an invasion in Ukraine sends an undeniable message to the world. Sudan’s junta has no interest in supporting democracy or the basic principles of sovereignty. We are watching,” Meeks stated in a tweet under the House Foreign Affairs Committee.

From Russia with guns

There may be a more chilling reason behind the Deputy Sovereign Council leader’s visit to Moscow: more arms to suppress the civilian protests against them. While Himmedti held talks with Russia’s Deputy Prime Minister, Alexander Novak, he also met Russia’s Deputy Defense Minister Alexander Fomin on Saturday to discuss military cooperation.

Moscow is considered the largest arms supplier to Khartoum. Long-term, advanced military relations exist between the two countries in terms of armaments, training and information intelligence via satellite. Russian arms trades are not exclusive to Sudan. Moscow’s first Russia-Africa summit of political and business leaders in 2019 produced contracts with over 30 African countries to supply military armaments and equipment.

Unconfirmed reports claim Himmedti discussed with the Russian government ways to directly supply arms to his militia, the Rapid Support Forces. If true, this may cause consternation for Burhan amidst reports alleging a potential rift between the Sovereign Council leader and his deputy.

While it is difficult to claim an arms deal with the army or expressly with the RSF was established, it is easy to see Russia’s military presence within Sudan. In past months, eyewitnesses told Ayin, military vehicles with Russian soldiers and officers have been spotted in Nyala, Sudan’s second-largest city in South Darfur State.

According to a former official at Sudan’s Foreign Ministry, Russia has provided training and intelligence advice to Sudan’s generals. This military support, the official said, may be linked to the targeting of pro-democracy demonstrators in the streets of Khartoum and elsewhere.

Russian military support is often provided indirectly through the Wagner security company, says diplomatic analyst Ezzeldin Omar, a company with alleged ties to Prime Minister Vladimir Putin. Omar adds that Wagner is making huge profits through agreements with Sudan’s military to support gold mine operations in the country.

Wagner across Africa

Russian mercenaries operate in parallel with the Kremlin and represent Moscow’s tool kit to prop up weak African leaders in exchange for economic advantages, says

Joseph Siegle, Research Director of the Africa Center for Strategic Studies. Whether in Libya, Central African Republic, Mali or Sudan, Siegle says, Russia’s Africa strategy focuses on propping up an embattled incumbent or close ally.

“The partnerships that Russia seeks in Africa are not state but elite-based,” he adds. “By helping these often illegitimate and unpopular leaders to retain power, Russia is cementing Africa’s indebtedness to Moscow.”

Praying on fragile states by offering military and diplomatic support remains Russia’s strategy across Africa, including Sudan, the former Sudanese official at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs told Ayin. As France gradually leaves the region, Russian presence on the continent is expanding, the official said, from Sudan, Chad, the Central African Republic, and Mali.

In Sudan’s case, Russia wants the military-led government to agree to a naval base in the Red Sea and to continue allowing them to have access to the landlocked Central African Republic where they control several mining operations.

If Sudan’s military leaders honour these agreements, the indefatigable protest movement against the coup will likely face more firepower and brutal suppression through Russian support, analysts said.

But new western sanctions targeting Russian banks, technology imports, and state finance institutions may severely curb the country’s arms production and thereby reduce Russian influence in Sudan. This, coupled with political isolation, may curb Russia’s influence in Sudan. In the end, Himmedti’s Russia visit may yield few gains and only help to isolate the military leadership from foreign support.