The Sungu mines — gold that fuels RSF’s war

18 January 2024

A collaborative report between Ayin and Darfur 24. Analytical, data, and imagery support provided by Washington, DC-based global security nonprofit C4ADS.

In Sudan’s current conflict, gold is a target of the war and helps fuel it. Both warring parties continue to rely on gold production as an integral means of financing the war effort. While the de facto government under military control in Port Sudan claims gold production in army areas has reached $150 million in monthly revenue, their adversaries, the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), may be accruing similar rates, according to gold smugglers and employees of the RSF gold mining and export company, Junaid.

Last year, the United States sanctioned the Junaid company, entirely RSF-owned, saying that gold had become a “vital source of revenue” for the RSF and their leader, Lt.-Gen. Hamdan Dagalo (aka “Himmedti”).

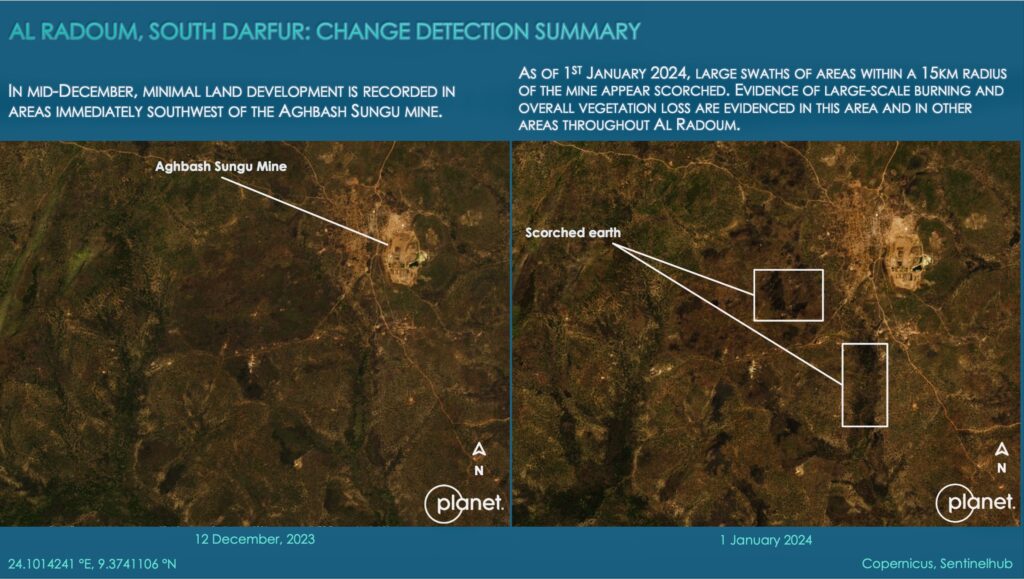

Despite disruptions and logistical challenges in mid-April last year, a joint Ayin / Darfur 24 investigation reveals that gold production in the western RSF-controlled areas of Sudan is now fully operational. The bulk of these gold mining operations are taking place in the al-Radom locality area of South Darfur State, an area under RSF control.

The RSF exclusively concentrates on the process of milling and treating soil and stone from mining sites, known locally as “karta,” to extract gold, and then exports the final product to their primary financiers, the United Arab Emirates.

The Emirates is a major hub for the RSF, which uses front companies controlled by Himmedti and his relatives to sell gold and buy weapons, officials say. Since the war started, the United States has imposed sanctions on 11 RSF companies, mostly in the Emirates, and often for their links to the gold trade.

While the arming of the RSF via the UAE is well documented, Russian involvement in RSF’s gold trade is also evident. According to a local administrative official in Sungu and corroborated by several local miners in the area, there are roughly 16–18 Russian nationals working within Junaid compound in the area.

The fight for gold

From the beginning of the conflict, gold was a praised asset for both warring parties and worth fighting for.

According to Sudan’s minister of minerals under the de facto army government, Bashir Abu Namu, the RSF seized 1,273 kilograms of gold upon the outbreak of war from a government refinery in the capital, Khartoum. A month later, in mid-May 2023, confrontations took place between the RSF and national army in the Sungu area, South Darfur State, resulting in the deaths of seven people, according to local residents. Determined to maintain control of the gold mines, the RSF seized the army garrison, ensuring them full control of the lucrative mining area, a Junaid employee told Ayin on condition of anonymity.

Desperate to curb the RSF’s source of income, Sudan’s airforce has repeatedly bombed the area. The latest air strike took place on 22 January against the Aghbash mine in the Sungu area, targeting warehouses and housing for some Junaid Company employees east of the market area.

According to mining researcher and security analyst Ali Hassouna, a Sudanese army offensive into Al-Jazeera State in early December was partially designed to ensure the RSF did not enter northern Sudan, where the gold mining sector is concentrated. “A year has passed since the Rapid Support Forces took control of Al-Jazeera State,” Hassouna said. “But their plans to mobilise their forces and expand into the north of the country, areas producing gold and other minerals, were thwarted by an offensive from the army. This has helped the army retain these mines and finance its military operations.”

Sungu mines, then and now

The war halted mining operations in the Sungu mines in the Al-Radom area of South Darfur State, roughly 360 kilometres south of the state’s capital, Nyala. Once sparsely populated, the area became a hub of activity and commerce as early as 2016, as gold prospecting took off. Prior to the conflict, roughly 100,000 local miners were active in the most prominent mines in the Sungu area, several miners told Ayin, namely, Agbash, Daraba, Thuraya, Wad Nyala, Sarfayaa, and Jumana.

But after the outbreak of war last year, insecurity and a dearth of fuel ceased all mining operations, according to an employee of Junaid, the only mining company now operating in the area. Upon the outbreak of war last year, says gold trader Hamid Youssef, many local miners left the mining altogether and joined the ranks of the Rapid Support Forces since limited fuel supplies curtailed mining operations.

Another Junaid employee, who preferred anonymity for security reasons, stated that they normally consumed a tank of fuel on a daily basis prior to the conflict. As fuel became scarce, the company was forced to give 70% of their employees open leave and operate with only a third of their workforce, slowing gold production to less than a ton per month.

By May 2023, however, operations commenced, and, after the rainy season from June to October, local traders and miners say operations in October 2023 and 2024 resumed in full swing. One of the few sources of employment, tens of thousands of local miners, traders, and soldiers circulate the area—if they manage to reach it safely.

Wild West mining

While mining provides the local community a source of employment, it is far from an effortless venture. Entering the mining area is fraught with dangers; any vehicle is vulnerable to looting, whether carrying miners on its way from Buram to the gold mines or motorcycle drivers who smuggle gold across the Chad border. Armed looting is frequent between the Sungu area and the Liebo village area, on route to Chad.

Even though local miners can dig with relative security, their hard work may not yield rewards once they leave the area to sell their gold. According to Hajj Obaidullah, a local gold miner, looting remains widespread as gunmen on motorcycles roam the perimeters. A looting incident occurs around the clock, Obaidulla said, making mining sales for locals working outside of the RSF-controlled company, Junaid, a constant challenge.

Local trader Fadl Bakhit believes that looting between mines is mostly based on information that reaches armed gangs through sources among the miners. Using local sources, the gang is notified of where and how much gold certain vehicles are carrying.

Musa Ghazir, an RSF soldier who transports passengers from Buram to the gold mines, reports that the RSF security forces, assigned to protect the market, now prohibit the carrying of arms. Previously, weapons were awash in Sungu, says resident Baba Allah-Eid, but after robberies and murders escalated, a local civil committee and the RSF developed a policy prohibiting anyone carrying weapons in the mining area. In fact, the Sungu mining area is one of the safest areas under RSF control, local residents told Ayin. The main market, Aghbash market, remains theft-free. Rather, merchant Hamdan al-Toum said that tarpaulins only cover goods, allowing their owners to sleep without fear of looting.

A local mining committee and the RSF reached an agreement whereby RSF patrols would comb dangerous roads several times a day. Vehicles transporting gold for local miners then agreed to pay 50,000 Sudanese Pounds (roughly $20) for armed security to accompany the vehicle.

The local tribal leadership runs a court and police force specifically designed to handle mining disputes and other altercations. However, social disputes are rare, partly since the local council has banned entry for women and children, ostensibly to curtail any disputes and ensure a consistent workflow.

And a constant workflow is exactly what the Junaid Company expects.

For miners working in the estimated 13 different mines within the area, the operations and personnel of Junaid remain shrouded in mystery. About 200 meters east of the Aghbash market, a high earthen fence surrounds the Al-Junaid Company, concealing its contents. The only thing the viewer sees are the lights and the mountainous buildings. According to several local miners working the Sungu area, a leader within the Habaniya tribe, Youssef Ali Al-Ghaly, helps in acquiring the karta and transferring the material for gold processing.

While the mines remain secure from looting within the Sungu area, local miners still face tremendous challenges. The rainy season, generally from June to October, has led to a scarcity of food imports into the area. In September, miners attempted to work with severe shortages in food supplies and subsequently prohibitively high market prices, says miner Saadan Musa.

But as soon as the rains stopped in October this year and fuel supplies arrived from Um Dukhum and Raja, South Sudan, local traders said, mining operations in the Sungu area resumed. Once the rain stopped, according to Musa, “tens of thousands” of miners came into the area by November this year, producing gold at levels found prior to the war.

Production

How much gold is procured from the Sungu mines in total and how much the RSF pockets from this massive operation, deemed the most productive mine currently under RSF control, remains a mystery. Since the outbreak of conflict, all RSF gold trade exports are smuggled with little signs of a paper trail to monitor production and shipments. Even the employees of RSF’s gold mining company are unaware of this issue. “We see it [gold] being packed for shipment, but we have no idea of the quantity—not even how much is made,” said an engineer who works for the company, requesting anonymity. “Ever since the war started, these operations have been shrouded in secrecy, and any leakage of such information could get you into trouble.”

Before the war, mining expert Abdullah al-Rayeh told Ayin/Darfur 24 the RSF produced an estimated 240 tons of gold over a seven-year period from 2015 to 2022, averaging 32 tons per anum. It was this revenue, al-Rayeh says, that ensured the RSF funding for military operations. The RSF has a ready market for its gold in the United Arab Emirates, where 2,500 tons of undeclared gold from Africa, worth a staggering $115 billion, were smuggled between 2012 and 2022, according to a recent study by Swiss Aid, a development group.

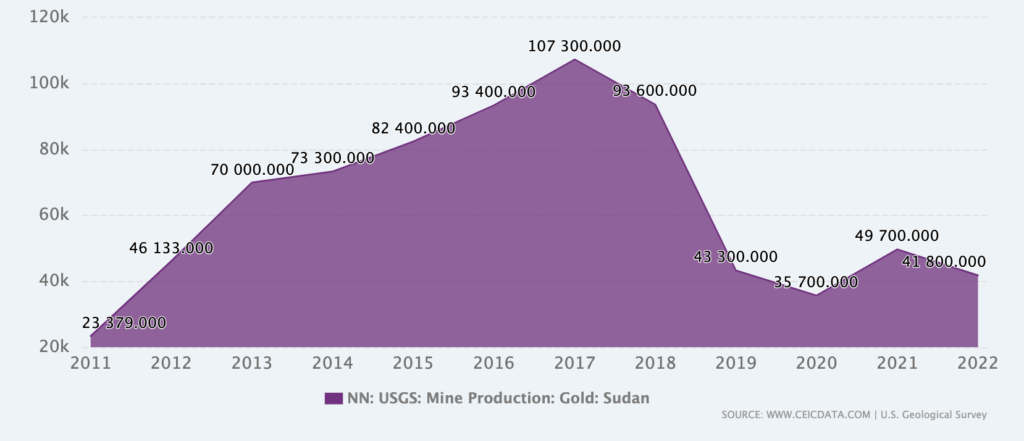

Official estimates of gold production across Sudan reached nearly 42,000,000 kg (roughly 46.3 million US tons) in December 2022, according to a report by CEIC, a company specialising in macroeconomic data, quoting the US Geological Survey. But official export rates hardly encapsulate the total gold exports from Sudan, says Alaa El Deen Faisal, an expert in the Sudanese mining sector, since a significant percentage of Sudan’s gold is smuggled out of the country, both currently and prior to the conflict.

The de facto government’s finance minister, Jibril Ibrahim, called on the armed forces to try to block gold smuggling during an economic conference held last November in Port Sudan, the capital of the army-appointed government. The minister claimed there is a huge difference between real production and official rates, given the widespread smuggling operations.

Mohamed Taher Omer, the director of the army-controlled Sudanese Mineral Resources Company, said they have earned $1.5 billion from gold exports in the first ten months of this year. According to statements from the director and the mining minister under the de facto government, the mines in the army-controlled areas have produced around 29 tons in the first eight months of 2024.

Albeit difficult to confirm, two separate sources—a Junaid employee and gold mining researcher, Ali Hassouna—both estimate the RSF have earned close to a billion dollars in gold revenue in 2024 from the gold mines under their control. A confidential report submitted to the United Nations Security Council in November seems to corroborate this. The report found that $860 million worth of gold had been extracted from paramilitary-controlled mines in Darfur this year alone.

However, according to Sudan researcher and founder of the think tank Sudan Transparency and Policy Tracker (STPT), Suliman Baldo, such RSF gold production estmitates may be exaggerated. Baldo believes gold production from the Sungu mines has not exceeded 600 kilograms in 2024 and that gold production from RSF’s other mine in Jebel Amer was already in steep decline.

Recently, new traders, mostly RSF leaders, drove a surge in gold prices at significant Darfur mines. According to one trader and RSF leader, gold prices rose from 160,000 SDG to 220,000 SDG (roughly $60-82) per gram in December in the Sungu area. After the army-controlled government introduced a new currency in December, many traders in the RSF-controlled areas are purchasing gold as a more secure means to save their wealth, given the tenuous status of Sudan’s current currency, the same source said.

While RSF gold production rates may be challenging to determine, the relatively successful gold sales made by local miners in the Sungu mines provide an idea of the region’s mineral profit viability. According to local gold trader Jamal Saad in April, the entire mining area can bring in roughly 2,000 grams of gold per day for local miners. At roughly $43 per gram, this is $86,000 per day and nearly $2.6 million per month. More recently, Sungu-based gold trader Abdalla Mohamed says one gram will earn roughly $56 at approximately $112,000 per day. A gold trader in Nyala, Abo Alladin, said a gram of gold can reach $71 in the market.

With thousands of miners operating in the area, along with mining and security fees instigated by the RSF and local tribal councils, few local miners profit significantly. Nevertheless, the al-Radom area, where the Sungu mines are located, represents one of the most affluent localities in South Darfur State, says local finance officer Mohamed Saleh Adam. Government licenses for machines, wells, and gold smelting equipment, Saleh added, all ensure high local revenues.

Where the gold goes

While Himmedti and his family associates who run Junaid were once able to simply export gold from Darfur to Khartoum and Port Sudan, the army’s bombing of Khartoum International Airport and control of the port-based city has forced the RSF to use more creative smuggling routes. According to local miners in the Sungu area, the Al-Junaid headquarters in Sungu is equipped with an airstrip that enabled a steady flow of air traffic to carry the gold before the war. Upon the outbreak of conflict, no plane would dare such a risky drop-off.

Up until late September this year, gold traders in Sungu said the RSF resorted to motorcycles to transport roughly 80% of their gold across the border through Chad’s rough terrain. The remainder, via South Sudan and the Central African Republic. While Chad may be the preferred route, gold smuggling through South Sudan must also be significant given the de facto government’s interactions with their counterparts in South Sudan. Last November, Sudan’s mining minister, Bashir Abu Namu, officially requested South Sudanese authorities to help track the movement of convoys carrying gold from Darfur during a conference.

Chad, however, remained the preferred route since Chadian authorities provided security and reduced import fees, the same sources said. Before September and when roads were dry enough to traverse during the rainy season, around 8-10 motorcycles—each heavily armed—would trek across Chad to eventually export the gold to its preferred destination, the Emirates.

Since 24 September 2024, however, some gold is being transported via land cruisers from Sungu to Nyala, South Darfur’s capital city, after the RSF managed to restore the airport, according to local traders and a senior commander within the Rapid Support Forces. This is corroborated by satellite imagery that indicates controlled fires around Nyala Airport, designed to clear brush and other debris from the runway (see below).

The Yale School of Public Health Humanitarian Research Lab (HRL) has used satellite imagery to identify 43 shipping containers appearing at Nyala Airport between 14 December and 12 January 2025. This research seems to strengthen claims by the army that Nyala Airport is being used to smuggle gold along with agricultural and livestock products to the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

The South Darfur State Governor Bashir Marsal also confirmed this, stating on “X” that gold is being smuggled from Sungo to the Emirates and that the repeated landings of Emirati planes pose a security threat. “The state is witnessing security threats represented by the repeated landing of the Emirati plane at Nyala Airport and other airstrips,” the governor stated. “The matter is related to national security.”

The governor’s concerns appear warranted. On 10 December, the army’s air forces bombed Nyala Airport and other locations within the city, including the state ministry of finance building and a military training camp, eyewitnesses said. This airstrike has occurred despite the RSF placing jamming devices in the airport’s transponders, local sources said. Since September, the airport has hosted nighttime cargo flights, remaining on the tarmac for less than 90 minutes to avoid attacks, the same sources revealed.

While insecurity may curb gold exports from Nyala Airport, the opportunities to sell gold and purchase weapons will likely be easier for the RSF in the future. Being closer in proximity to the Sungu mining area, local traders said, the easier it will be to ship to the Emirates. Armed RSF personnel guard the transport of gold from the mines in Sungu to Nyala.

Since September, citizens living in areas along the road from Sungu to Nyala have seen heavily guarded land cruisers headed to the headquarters of the Junaid company. According to one observer in Nyala living relatively near the airport, throughout October and November, planes have landed at night and depart at dawn on a regular basis.

However, satellite imagery from Yale’s HRL also indicates munition attacks by Sudan’s airforce, making the runway at Nyala Airport difficult to use. An open-source intelligence analyst, Faisal El Sheikh, believes reports of Nyala Airport’s use have been exaggerated, claiming the airport remains too damaged for such commercial flights.

Whether Nyala Airport is fully functional or not, it is clear the RSF company, Al-Junaid, plans to use the city as a base for trade and exports. The Junaid Company silently moved its headquarters, including administrative and executive staff, to Nyala once the RSF took control of the city in October last year. The company is under the supervision of the RSF South Darfur State Commander, Colonel Saleh al-Futi, according to a Junaid employee.

More gold, more weapons

“Gold is the new conflict diamond,” says political analyst Mohamed Ibrahim. “Both sides are heavily invested in the gold mining trade, and both sides rely on this to support the war effort.” According to Hassouna, gold profits were instrumental in their RSF’s purchase of drones and training soldiers to use them.

In October and November, the RSF made extensive use of drones in El-Fasher, Merowe, Atbara, Shendi, and Omdurman—targeting areas previously unreachable for the paramilitary force. C4ADS has managed to identify evidence of the RSF purchasing drones in 2024.

Based on current mining operations and interviews with local gold traders, mining in the Sungu area appears set to continue and to even expand production. Given these prospects, the paramilitary’s war machine is likely to persist, with minimal prospects for a peaceful resolution to a conflict that has precipitated one of the world’s most severe humanitarian crises.