The war in Sudan silences journalists, coverage

21 January 2024

This report was done in collaboration with the Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ) organisation.

Manal Ali* woke up from the blow she received to her head and slowly began to regain consciousness. Despite the confusion she felt from the impact of the blow; Ali still remembers the last scene of that day; on her way to the bakery in Geneina, the capital of West Darfur State. A car with masked men stopped near her, she heard a voice calling her name and then nothing.

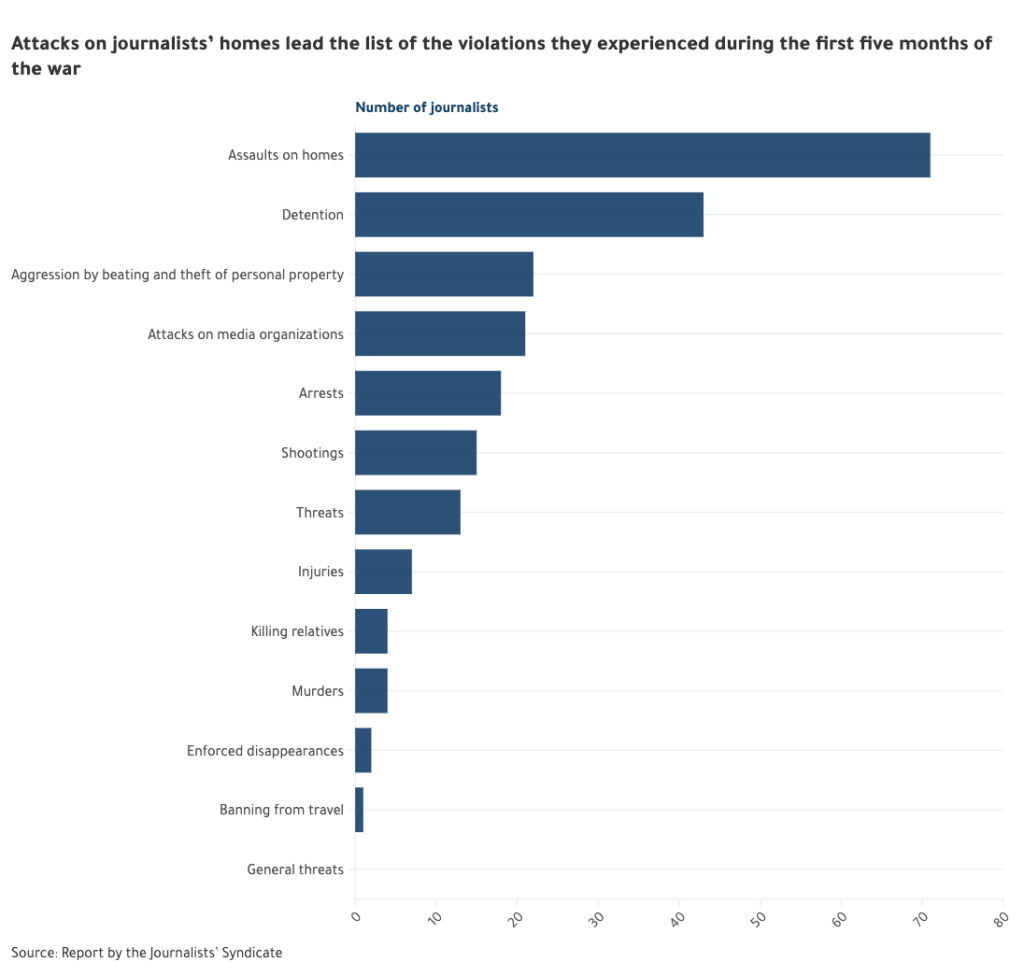

Manal Ali is an independent journalist, and one of more than a hundred journalists who were arrested, tortured, and threatened by both sides of the conflict in Sudan, for merely trying to report on the reality that the Sudanese people are living through. The war has forced journalists into silence, amidst threats and attacks by the warring parties, leaving a dangerous information vacuum in its wake.

On the morning of Saturday, 15 April, clashes rang out in the capital, Khartoum, between the forces of the national army led by Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan, and forces of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as “Hemedti.” The army and RSF were former allies who overthrew a popular revolution that started in 2018. By mid-April last year, however, a war of dominance erupted between them, and truth became the first casualty.

Mass media closures

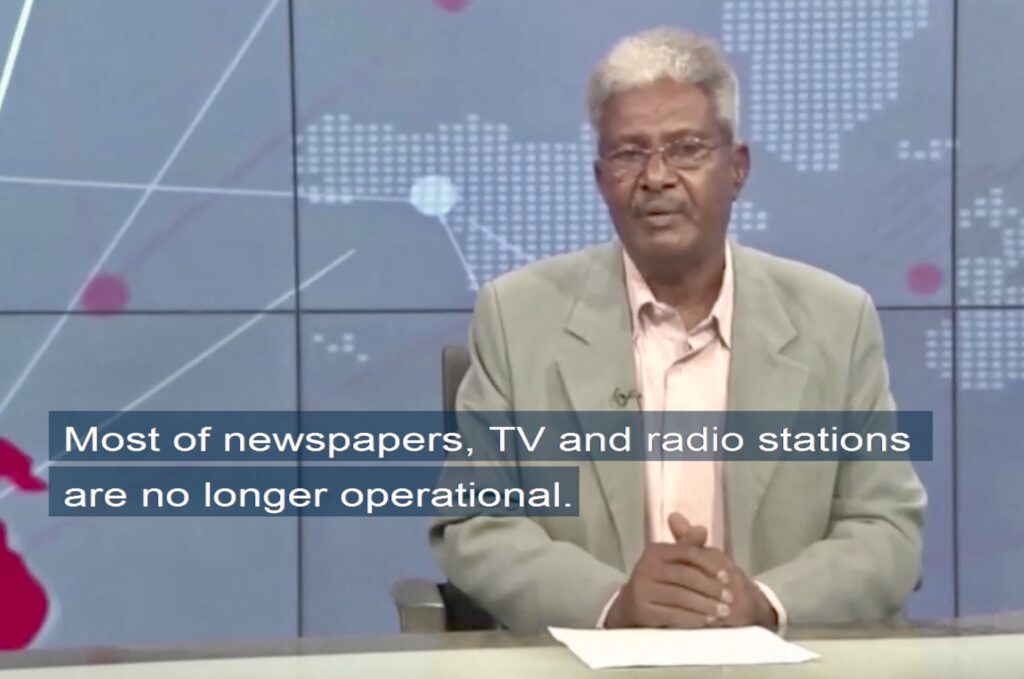

According to Iman Fadul, the Press Freedom Officer from the independent Sudanese Journalists Syndicate, most media houses have shuttered while journalists have gone into hiding –creating a void in credible information in the process.

As of November last year, Fadul told Ayin, 26 newspapers have stopped publishing, and 17 radio stations closed down, except for two radio stations operating inconsistently in the cities of El Obeid and El Fasher.

Six television stations based in the capital, Khartoum, also shut down, she said, most of which abruptly terminated their staff’ employment without any compensation. The national broadcaster, which employed over a thousand people across the country, stopped paying salaries since the war started, Fadul added. From the onset of the war, the premises of the National Radio and Television Corporation were taken over by the RSF and have been turned into military barracks since.

In December, the Syndicate denounced the RSF’s use of the buildings of the state broadcaster, the Sudan Broadcasting Corporation (SBC), as makeshift detention centers and the sale of SBC equipment in markets in Khartoum’s sister city, Omdurman.

Targeted from both warring parties, many journalists have either gone into hiding or have found themselves “taking sides” as a means of survival. “The war forced Sudanese journalists to hide their identity, as they cannot disclose their profession to either of the warring sides,” Fadul said. “In the eyes of the two warring parties, journalists are criminals due to their efforts to highlight the facts while the army and RSF continue to spread rumours and fake news.”

In November last year, the RSF took control of two state capitals in Darfur, Geneina, and Nyala, and then re-opened the state radio stations, local residents told Ayin. “Nobody listens to their station,” said Atif Suleiman* based in the outskirts of Nyala, the capital of South Darfur State. “They just broadcast their propaganda throughout the day.”

Targeted from both sides

Targeted from both sides

Before fleeing the country, Manal Ali remembers how the RSF were targeting journalists. “The homes of journalists were singled out; they had a list of our names, and the RSF were searching for us by name. They destroyed my house completely.” On the first day of the war, Manal lost seven members of her family, including her brother.

As part of her job, Manal Ali received reports of rape incidents that took place in Darfur State, specifically in Geneina where she used to live. “There were recordings for nine cases of rape, and I was communicating with the victims before communications were all cut off.” Ali says that she received a phone call in which the speaker threatened to kill her if she published any details about the rape incidents.

The real nightmare, however, started on 23 April, a day after the war broke out in Geneina when Ali was kidnapped by masked men wearing the uniform of the Rapid Support Forces. She said that on 27 April, they beat her until she lost consciousness. On the same night, Ali was found in an area close to where she was kidnapped, lying near the neighbourhood mosque in a critical condition. She was treated and later transferred to her family’s home, after which she began her journey to escape the war as she crossed into Chad.

Ali Tariq, a journalist who works for Al Jarida newspaper, left Khartoum as the clashes escalated and headed to his hometown in Sennar State. On 16 August, he was summoned to the army’s General Intelligence Service, following a press report he had published about the conditions of those fleeing Khartoum to the city of Sinja in Sennar State and documenting the harassment experienced by the displaced in the shelters provided.

The security authorities rejected the accusations about their inability to provide a suitable environment in the shelters and claimed that these were baseless claims. Tariq was imprisoned, and his family was not allowed to communicate with him or to know anything about him. He was only released when he went on a hunger strike on the fourth day of his detention. Tariq says he was warned against writing about humanitarian issues related to displaced people and against naming the General Intelligence Service in future pieces.

Italian journalist Sara Creta arrived at the Sudanese-Ethiopian border on 7 May –three weeks after the outbreak of clashes. The Sudanese authorities did not allow her to enter the country; she was detained by the Military Intelligence Department in the border region for a few hours, and she was asked to return to where she came from. The journalist works with several international channels, including Al Jazeera and The Guardian, and she tried to enter again through the Blue Nile region, but she was denied access to Damazin and was asked to leave.

“They told me that they cannot guarantee my safety there, and currently they told me, there are orders prohibiting the entry of foreigners,” Creta told Ayin. “The situation is volatile, I meant to stay in an area where there was no fighting. Both factions used the same language, so I felt that they were using the security argument as an excuse.”

Online wars

The war and the targeting of the press are not exclusive to the battle zones –social media platforms have also joined the conflict where journalists are often the primary target. Both warring parties have inundated social media sites, especially Facebook, and now the RSF features heavily on Tik-Tok. When journalists shared news and narratives, lists were published that affiliated them with one of the two warring sides. This led to the spread of hate speech against journalists from unknown entities, and an exchange of accusations amongst journalists themselves on social media platforms.

On 19 January, unknown parties shared social media posts accusing journalist Shahdi Nader, a correspondent for Al-Arabiya and Al-Hadath channels, claiming Nader was an agent for the army and helped coordinate bombing attacks, according to a statement from the journalists’ union. The Sudanese Journalists Syndicate condemned the post, saying the claim is unfounded and designed to intimidate and threaten journalists.

Hiba Abdel Azim is an independent journalist who was threatened by her colleague in a WhatsApp group, which includes more than sixty-seven journalists most of whom are reporters, following a discussion about who started the war. “Initially, I brushed off the threat, but what really scared me was that the person knew where our house was and knew all my family members,” Azim told Ayin. “The threats to come to the house terrified me, so we decided to leave home.”

Samar Suleiman had a similar experience; she received threats through the Messenger application, including one from a former minister. She was also asked to broadcast television material on the satellite channel she used to work for, in return for a financial award. When she refused the offer, she was threatened that she would be reached and dealt with after the end of the war.

On the run

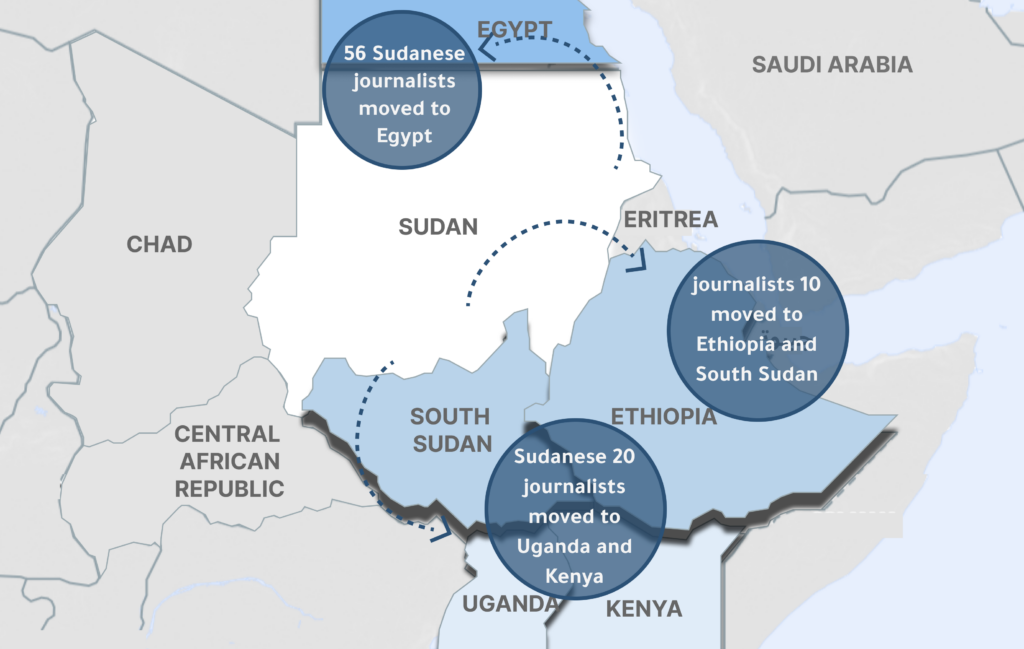

The ongoing threats against Sudanese journalists -whether in person or online- have led to scribes being either internally or, more often, externally displaced. According to the UN, Sudan has the highest rate of displacement in the world –with 6 million people internally displaced and another 1.7 million who have fled across the country’s borders.

Al-Khair, a field correspondent for the independent broadcaster “Sudan Bukra”, fled Khartoum in May 2023 to the eastern city of Gedaref intending to cross the border into Ethiopia. At the Al-Duqa checkpoint, Military Intelligence officers accused him of an affiliation with the RSF, just because his passport indicated that he was born in Nyala, Darfur.

The army officers took him to a blood-stained room to force him to confess to belonging to the RSF, where he was beaten and abused. While searching his belongings, journalistic material that focuses on the root causes of the popular uprising was found. This would have complicated matters more, but he told them that he had left work for that channel months ago. Abbas Al-Khair says he was only released after one of his relatives who is an officer in the Sudanese Armed Forces was contacted.

The head of the Journalists’ Syndicate Abdel Monim Abu Idris confirmed that the international organisations Committee to Protect Journalists, and Reporters Without Borders have helped evacuate several journalists from Sudan, and there are ongoing attempts to evacuate more of them. According to Abu Idris, the majority of journalists left for Egypt.

An information vacuum

The constant threats against journalists reporting in Sudan, often compelling them to flee the country, coupled with the mass closures of media houses has led to a dangerous dearth of accurate information at a time when citizens desperately need reliable coverage.

In a survey among Sudanese civilians concerning access to information conducted by Ayin, citizens confirmed that they often rely on phone calls from friends to receive updates since they cannot rely on the local media anymore. Most local media houses are now either shuttered or have become mouthpieces for one of the warring parties, survey respondents told Ayin. This latter phenomenon can, survey respondents said, lead to the prolongation of the war, spreading hate speech –even encouraging geographical separations and social divisions.

“Since many media houses have taken sides in this war, people have lost trust in these platforms and rely on social media instead,” says Haitham Ali, a former university student in Khartoum who was forced to flee north of the capital to Wadi Halfa. “But trying to get an accurate picture from social media is also challenging –which is exactly how those supporting the war want it to be. We are kept in the dark.”

* The name has been changed for security purposes